Up to 80% of threatened and commercial species across European marine protected areas face novel climates under high emission scenario

Introduction

Climate change, driven by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, poses a significant threat to the health and stability of marine ecosystems worldwide1,2,3,4. Observed environmental changes are already affecting the behavior, physiology, and geographical distributions of marine organisms, forcing species to migrate poleward in pursuit of suitable habitats5,6,7. These range shifts, which may result in local extinctions and altered community structure8, are particularly concerning for species already listed as threatened by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, as well as for species impacted by fishing pressure, or a combination of both. Importantly, future climate change projections under higher greenhouse gas emissions, e.g., the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) 5–8.5, consistently show significant changes in ocean temperature, pH, oxygen levels, and productivity, further jeopardizing the survival and adaptability of marine organisms9,10. These projected changes in marine ecosystems also have the potential to erode the natural capital underpinning societal well-being and prosperity in the future, threatening planetary boundaries11,12.

Marine protected areas (MPAs) are established worldwide to support and safeguard biodiversity and ecosystems via the maintenance of essential ecological processes13,14. Although MPAs provide benefits for climate change mitigation through, for example, fostering ecosystem resilience and enhancing carbon sequestration15,16, they are not universally designed to withstand the impacts of climate change17. The designation of MPAs typically disregards the risk of future climate change18 (but see ref. 19) despite an increasing body of evidence demonstrating their vulnerability to climate change20,21. MPAs are more likely to successfully protect species and habitats when serving as climatic refugia, i.e., providing stable and suitable climatic conditions for the long term22. On the other hand, regions exposed to novel climatic conditions (novel to that region and species) might not provide the required conditions for local species to prevail23. As species may adapt to shifting climatic conditions by modifying their distribution patterns24, this can lead to movements beyond the boundaries of existing MPAs, casting doubt on the ability of MPAs to cope with future climatic changes25.

European seas, particularly enclosed or semi-enclosed seas such as the Baltic Sea and Black Sea, are experiencing some of the most rapid temperature increases globally26. They are also the regions with the highest concentration of MPAs in the world27,28. Previous efforts to estimate the potential effects of climate change on European MPAs have considered simplistic indicators like climate velocity changes as proxies for species’ exposure to novel climatic conditions25,29,30. Such approaches, however, have two main limitations that might have precluded conclusions regarding climate change effects, namely, (i) they have focused on sea surface temperature, overlooking biologically meaningful environmental variables like oxygen levels, pH, and primary productivity, which also influence species distribution31 and (ii) considered solely climatic conditions changes, disregarding species-specific niches. To address these limitations, alternative approaches have been proposed, notably climate novelty analyses, which have been previously used for terrestrial protected areas32,33, and present a promising avenue for studying climate change impacts on marine ecosystems.

In this study, for the first time, we conduct a multivariate climate novelty analysis to understand to what extent species within MPAs are exposed to future novel climates, hereafter also referred to as at-risk species and MPAs. We focus on European MPAs and their threatened (IUCN Red List) and/or commercially important species, as these groups are typically the main targeted species of MPAs’ objectives and respective conservation measures. We determine future climate novelty of target species within and beyond MPAs based on temperature, oxygen, pH, and primary productivity, and information on species distribution ranges. The analysis spans from the current climate conditions to end-of-century projections under two contrasting SSP scenarios (the low carbon emission SSP1–1.9 and the high emission scenario SSP5–8.5). Our approach provides novel and comprehensive insights into the potential impacts of climate change on threatened and/or commercial marine species and the vulnerability of European MPAs. Identifying at-risk species, i.e., exposed to future novel climates across their range, allows for the development or adjustment of management strategies and interventions within MPAs, increasing their overall efficiency and efficacy. This information is timely as we move into the era of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, a pivotal conservation initiative targeting the protection of 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030 and the concurrent mitigation of and adaptation to climate change.

Results

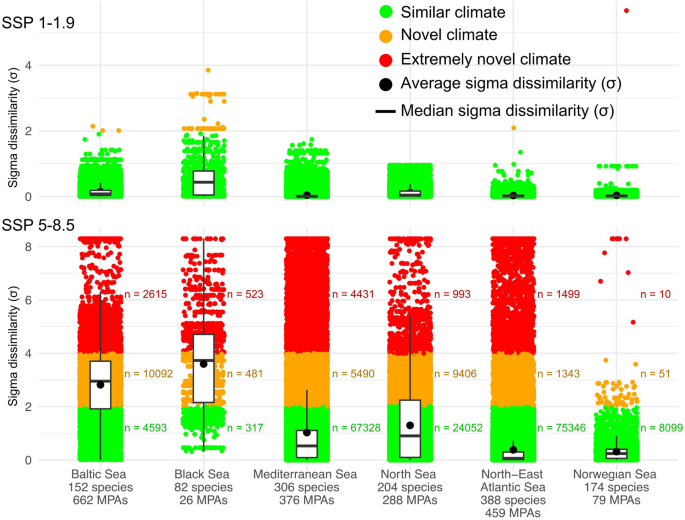

The exposure of 398 threatened and/or commercial species within 1890 MPAs to novel (2 < σ < 4) and extremely novel (σ > 4) climates varied significantly depending on the emission scenario considered. Under the low emission scenario (SSP1–1.9), all European sea regions maintain an average and median sigma dissimilarity (σ) below 2 (Fig. 1), with 0.5% of MPAs projected to harbor at least one at-risk species (i.e., experiencing novel or extremely novel future climate conditions). Likewise, only 6.5% of species are projected to be at risk in at least one of their resident MPAs. In contrast, under the high emission scenario (SSP5–8.5), 87.2% of MPAs and 80.7% of species are expected to be at risk. Specifically, 79.0% of MPAs are projected to contain at least one species exposed to novel conditions, and 63.2% exposed to extremely novel conditions. In parallel, 75.6% of species are anticipated to be exposed to novel conditions and 67.6% to extremely novel conditions within at least one MPA. Considering climate novelty across species ranges (SSP5–8.5), the Baltic and Black Seas are projected to face novel climates (average σ = 2.82 and 3.6, respectively), while the Mediterranean, North Sea, North-East Atlantic, and Norwegian Sea are projected to be less impacted (average σ = 1.0, 1.3, 0.4, and 0.3, respectively). However, under the SSP5–8.5, we identified numerous species–MPA combinations across the six regions with novel (26,863 in total) and extremely novel climate (10,071 in total, Fig. 1, orange and red dots).

The points represent σ for each threatened and/or commercial species and MPA combination within regions. Green points indicate similar climate conditions (σ < 2), orange—novel climate (2 < σ > 4), and red—extremely novel climate (σ > 4). The numbers in the SSP5–8.5 scenario indicate the total number of species–MPA combinations in each category.

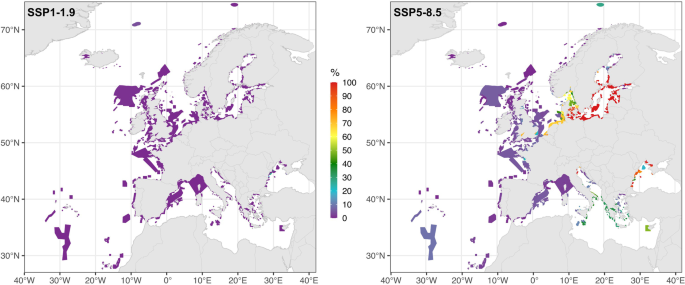

The proportion of threatened and/or commercial species projected to be at risk within each MPA across European sea regions is close to zero under the SSP1–1.9 (Fig. 2). Under the SSP5–8.5, several regions emerge as hotspots where a substantial proportion of species are projected to be at risk in many MPAs. Specifically, in the Baltic Sea, more than half of the analyzed (439 out of 662) MPAs contain more than 50% of species at risk, with 380 MPAs showing 100% at-risk species (Fig. 2, S1, panel d). In the Black Sea, all 26 MPAs contain more than 20% of species at risk; within these, 20 MPAs have over 70% at-risk species (Fig. S1, panel f). In the North Sea, more than one-third of the MPAs (99 out of 288) contain between 50% and 100% of species at risk, primarily in eastern regions along the coasts of Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and southern Norway (Fig. S1, panel b). Lastly, in the Mediterranean, 92 out of 376 MPAs contain between 20% and 50% of species at risk, mainly located in southern Italy, Malta, Albania, Greece, and Cyprus. However, the most impacted MPAs in the Mediterranean, with up to 100% at-risk species, are those in the northern Adriatic Sea, along the coast of Italy (Fig. 2, S1, panel e). In contrast, in regions like the Norwegian Sea, North-East Atlantic, western parts of the North Sea and the Mediterranean, most MPAs have <10% of species expected to be at risk, even in the high emissions scenario (Fig. 2, S1, panel a–c and e).

Results are shown for each marine protected area under SSP1-1.9 (left panel) and SSP5-5.8.5 (right panel). Zoomed version of SSP5–8.5 for each region is in Fig. S1 (Supplementary Material).

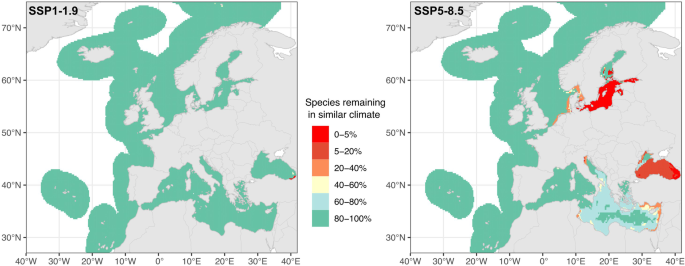

Across the six regions, the proportion of threatened and/or commercial species exposed to similar climates (σ < 2) under the SSP1–1.9 (Fig. 3, left panel) is 80–100% for all regions. Under the SSP5–8.5, the North-East Atlantic, Norwegian Sea, and western parts of the North Sea and the Mediterranean display very high percentages of species (80–100%) exposed to similar climates (Fig. 3, right panel). On the other hand, the regions previously identified with most at-risk MPAs, are projected to have very low percentages of species (0–5%) exposed to similar climates. The region with the lowest number of species with similar climates is the Baltic Sea (0–5%), specifically the southern half, followed by the Black Sea (0–20% in most parts). Eastern coastal areas of the North Sea and Mediterranean Sea are projected to maintain 20–40% of species with similar climatic conditions (Fig. 3, right panel).

Results are shown for each European sea region under SSP1–1.9 (left panel) and SSP5–8.5 (right panel) scenarios.

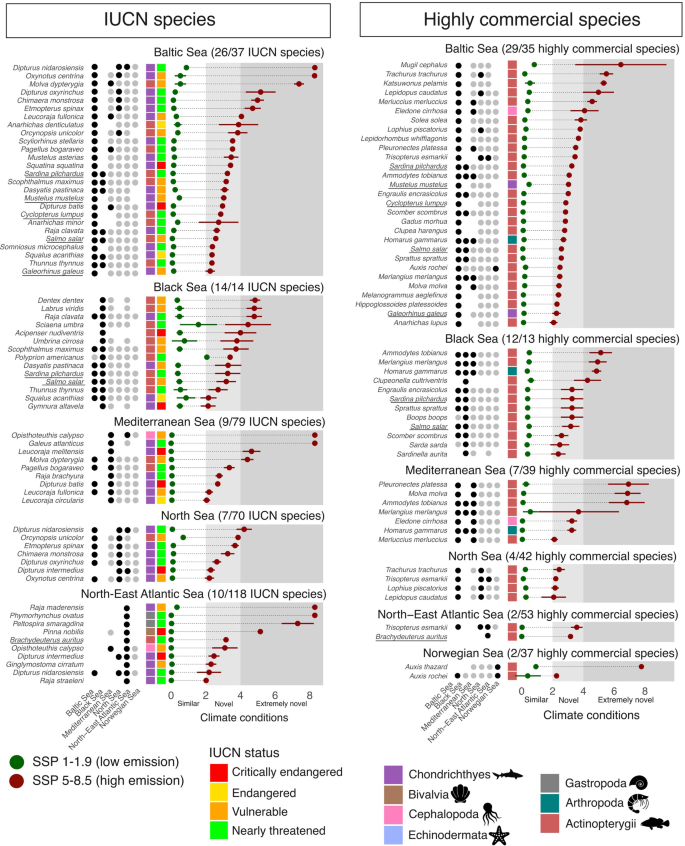

Under the SSP5–8.5, the vast majority of species within MPAs and across groups are projected to be at risk, i.e., 223 out of 276 commercial species, 14 out of 22 IUCN species, and 36 out of 100 species that are both IUCN and commercial species. Many of the IUCN-listed species projected to be at risk fall into the near-threatened category (n = 21), followed by vulnerable (n = 15), critically endangered (n = 7), and endangered species (n = 3). These species predominantly belong to the Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fishes including sharks, rays, and skates, n = 25/46) followed by Actinopterygii (ray-finned fishes, n = 17/46) classes. The Black Sea emerges as the most impacted region, with all IUCN-listed species (14 in total) anticipated to be at risk (Fig. 4). The Baltic Sea is also highly affected, with 26/37 IUCN-listed species projected to be at risk. In contrast, a lower proportion of IUCN species are predicted to be at risk in the Mediterranean (9/79), North Sea (7/70), and North-East Atlantic (10/118). Interestingly, none of the IUCN-listed species in the Norwegian Sea are expected to be at risk under the high-emission scenario. Furthermore, 36 highly commercial species (out of 55 highly commercial species in total), predominantly Actinopterygii, are projected to be at risk under the SSP5–8.5 (Fig. 4). In the Black Sea, almost all (12/13) highly commercial species will be at risk. This is followed by the Baltic Sea, where 29/35 highly commercial species are projected to be at risk. In other regions, this proportion is smaller: 7/39 in the Mediterranean, 4/42 in the North Sea, 2/52 in the North-East Atlantic, and 2/37 in the Norwegian Sea (Fig. 4).

Projected climate categories (x-axis) are similar climates (σ < 2), novel (2 < σ < 4), and extremely novel climates (σ > 4). Only species with an average σ > 2 (at-risk species) within MPAs in the SSP5–8.5 scenario are displayed: the IUCN Red List (left panel) and highly commercial species (right panel). The underlined species are those occurring both in the left and the right panel (both listed in the IUCN Red List and as highly commercial). The dot plot on the left of each panel is showing the other regions where species also occur within MPAs with black dots indicating σ > 2 (at risk) and gray σ < 2 (not at risk) under the SSP5–8.5. Full list of species projected to be at risk in each of the regions is in Fig. S2 (Supplementary material).

Many species have distribution ranges within MPAs spanning two or more of the six regions (Fig. 4). In most of these cases, under the SSP5–8.5, species are projected to maintain similar climatic conditions in at least one MPA. On the contrary, species with narrow distribution ranges (occurring only in one region) are projected to experience more drastic climate change effects. For instance, in the Black Sea, the critically endangered Fringebarbel sturgeon (Acipenser nudiventris) and the highly commercial Black and Caspian Sea sprat (Clupeonella cultriventris), fall into this category. Similarly, in the Mediterranean Sea, the critically endangered Maltese ray (Leucoraja melitensis) is projected to be at risk in all the MPAs. Moreover, in the North-East Atlantic, we identified six species, all exclusive to that region, that will be at risk within the existing MPAs. These include two types of skates (Raja maderensis and Raja straeleni), a shark species (Ginglymostoma cirratum), two sea snails (Phymorhynchus ovatus and Peltospira smaragdina), and a ray-finned fish (Brachydeuterus auritus), the latter of which is also a highly commercial species (Fig. 4).

Discussion

This study evaluated the exposure of threatened (IUCN Red List) and/or commercially fished species within European MPAs to end-of-the-century climatic conditions. Overall, our results show that the exposure of species largely depends on the emission scenario considered, underscoring the significance of greenhouse gas mitigation strategies and compliance with the Paris Agreement34. Under SSP1–1.9 (low emission scenario), most MPAs and their resident species are projected to experience similar climatic conditions to the ones they currently experience. This increases the likelihood of preserving existing ecological functions and biodiversity in these areas22. In contrast, under SSP5–8.5 (high emission scenario), more than 80% of the species and MPAs are expected to face novel or extremely novel conditions (i.e., be at risk) within their MPAs. This can impact the resilience and adaptability of marine species and reduce the overall efficacy of MPAs in achieving their conservation objectives.

Within the high-emission scenario, we show variability in exposure to novel conditions across regions. The highest proportion of at-risk species are predominantly located in regions and MPAs of enclosed and semi-enclosed seas, such as the Baltic Sea (more than half MPAs with 100% of at-risk species), the Black Sea (77% of MPAs with 70% of species at risk), and eastern parts of the North Sea and Mediterranean Sea (more than one-third of MPAs with 50–100% at-risk species and one-fourth of MPAs with 20–50% of species at risk, respectively). Even though our results show that species in MPAs of the western Mediterranean Sea will be less impacted, several MPAs with up to 100% at-risk species emerge in the north Adriatic Sea along the Italian coast. All these regions, with their unique biogeographic complexities, face additional human-induced stressors35,36,37. In response to the multi-layered pressures, numerous MPAs have been designated under directives such as Natura 2000 and through regional cooperation efforts like the Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission—Helsinki Commission (HELCOM) for the Baltic Sea, and the Bucharest Convention for the Black Sea. Despite such conservation efforts, future climate novelty will likely hinder the effective protection of threatened and commercial species currently residing in these regions. Further, locally adapted species with reduced genetic variation and relative isolation in these regions are still especially vulnerable to environmental shifts as they have limited movement options38. With these geographical constraints, these species are particularly at risk of potential extinction if unable to adapt in situ7. Thus, for these regions and for the outlook of marine species and ecosystems in general, a global reduction of greenhouse gas emissions is imperative to ensure long-term effectiveness of MPAs for local marine populations.

We also revealed the areas where studied species are expected to experience stable climate conditions, even under the high emission scenario. Specifically in the North-East Atlantic, Norwegian Sea, western parts of the North and Mediterranean Seas, and northernmost parts of the Baltic Sea. Identifying and preserving climatically stable areas, which can serve as refugia or essential migration corridors for species adapting to climate change, is key for evolving conservation strategies into climate-smart MPAs39. However, even in these regions where most of the species will remain in similar climates, we have identified some key species that will be exposed to novel and extremely novel climates. Moreover, despite the anticipated climatic stability in these regions, species residing there are still under pressure from human activities, even within MPA borders. Currently, most European MPAs lack strong protection and are minimally regulated or even unregulated, allowing destructive activities40,41,42. For instance, significant portions of European MPAs are known to be trawled, leading to considerable declines in species abundance40. It has been shown that only fully or highly protected MPAs can significantly decrease human impacts on biodiversity, resulting in positive ecological outcomes43,44,45, including resilience to climate change16,46. This underscores the complexity of ensuring effective protection and highlights the need for comprehensive approaches that address both climate stability and other pressures.

Throughout all regions, more than half of the species projected to be at risk in their MPAs under the high emission scenario belonged to Chondrichthyes (i.e., sharks, rays, and skates). Most of these are also of commercial value or were until they were listed as threatened by the IUCN Red List. These species play a crucial role in the maintenance and regulation of marine ecosystems, often acting as apex or key mesopredators47. Their potential exposure to novel climates may have cascading impacts on marine food web48. This could affect overall ecosystem stability and services, even in regions where a relatively low percentage of species are exposed to novel climates in the future. Some of these species, for example, different species of skate, have small home ranges and high site fidelity, particularly during critical life stages such as spawning and feeding seasons49,50,51. This can limit their ability to occupy new areas, given that species dispersion largely depends on adult movements. In our analyses, we found several skate species projected to be at risk across MPAs under the high-emission scenario. This includes the endemic Madeiran skate, Raja maderensis, and the Spotted skate, R. straeleni, with its current range around the Canary Islands and along the African coast52. When coupled with their slow life-history traits (e.g., slow growth, late maturation, low fecundity, and prolonged gestation periods), this could significantly elevate the risk of local extinctions for these species53. Contrastingly, sharks generally have larger home ranges, making their conservation within MPAs a challenging task for different reasons54. Many shark species undertake extensive migrations for feeding or breeding, often crossing hundreds or even thousands of kilometers55. Some of these shark species, including Galeorhinus galeus, Somniosus microcephalus, and Squalus acanthias are projected to be at risk in some of their distribution ranges. Even though these wide-ranging species typically face different environmental conditions along their migratory pathways, significant changes may potentially disrupt sharks’ traditional routes or habitats56. Our findings showing regions with both generally low number of species exposed to novel climates and key species facing novel and extremely novel climates, stress the need to identify priority species for conservation. This step will inform and refine future conservation strategies, ensuring targeted protection efforts where they are most needed.

We provide a basis for planning future climate-smart MPAs by highlighting both at-risk and not-at-risk species, MPAs, and regions under future climatic changes. This allows targeted protection across the full range of climate change impacts, serving as a crucial component of forward-thinking management strategies39. The observed differences in exposure to novel and extremely novel climates across regions and species emphasize the need for species-specific and region-specific climate change research10, a topic that has been notably understudied for many marine species in Europe57. Moreover, our results have important implications for MPA governance in Europe, including that existing business-as-usual governance arrangements are not sufficient. Research effort in relation to marine governance has increased significantly in the past decade58,59,60, but it has focused largely on responding to environmental change. While such reactive approaches to governance may facilitate incremental improvement, they are unlikely to deliver the shifts that are needed to ensure MPA effectiveness considering the findings presented here. Delivering transformation at the scale needed to safeguard marine futures for societal well-being requires proactive governance approaches where decision-makers can implement forward-looking interventions in the present in anticipation of future environmental change. Despite the plethora of technical work in relation to marine future thinking (e.g. foresighting future scenarios61), understanding how to transform marine governance arrangements in Europe remains critical. This transformation is necessary to become more forward-looking so decision-makers can understand and proactively develop actions to set pathways for ocean and human health62.

While we offer valuable insight regarding the exposure of threatened and/or commercial species to future climate change, we acknowledge several limitations of this approach. By assessing the dissimilarity between current and future climate conditions, we obtain species’ novel climates and, hence proxies of their future risk that are limited by current knowledge and environmental projections. Although we focused on a multivariate approach with four variables affecting species distribution, there are other unconsidered environmental variables, such as salinity63. This concern is applicable to other disregarded pressures64, such as overfishing65, pollution, or habitat damage known to affect species health66. It is also worth noting that the IUCN classification system, while valuable, may not be suitable for some organisms67. As this study focused on evaluating the future exposure to climate change of a subset of species currently present in European MPAs, we did not account for species that might migrate into or out of the MPAs due to climate-induced range shifts. The arrival of new species may lead to substantial alterations in community compositions68, potentially disrupting established predator–prey relationships and intensifying competition for resources6,69. However, the functional overlap between new species arriving and current threatened native species can aid in the preservation of the ecosystem’s overall functionality70. Additionally, extending climate exposure analysis to include species beyond our target group would enable a more thorough assessment of the climate change on European MPAs and Seas. We recommend that future studies include all these aspects to offer a more comprehensive understanding of climate change effects, not only on individual species but also on the overall ecological dynamics within MPAs. Finally, while we provide insights into regions projected to maintain similar climates (e.g., western Mediterranean), we recognize that considerations of climate change are just one of many factors essential for optimizing MPA functionality71,72.

Conclusion

Our findings underscore a concerning prevalence of threatened and commercial species and MPAs at risk under the high-emission scenario (SSP5–8.5). This highlights the imperative to pivot towards a low-emissions scenario. Concurrently, enhancing protective and proactive measures within existing MPAs and instituting adaptive management practices will significantly bolster the resilience of species and habitats facing multifaceted threats, notably related to climate change. Timely dissemination of this information is crucial, especially as we transition into the era of the recently ratified Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and the European Biodiversity Strategy. These frameworks delineate ambitious conservation objectives for 2030 and stress the nexus between climate change and MPA efficacy. In light of our study’s revelations, there exists a critical opportunity to expand the roster of species safeguarded under the Habitats Directive and Regional Sea Conventions (OSPAR, HELCOM, Barcelona, and Bucharest). This expansion should encompass all identified threatened and commercially significant species susceptible to future climate alterations. Updating this list will facilitate strategic augmentation of the MPA network in the coming years. Furthermore, planners of MPAs might need to contemplate safeguarding species that perform similar ecological functions yet demonstrate greater resilience to impending climate shifts. Nonetheless, our research underscores the indispensable value of adhering to the Paris Agreement to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions. This adherence is crucial to ensure the enduring effectiveness of European MPAs in safeguarding numerous threatened and commercially valuable species amidst the challenges posed by climate change, in addition to being pivotal for the survival of life on Earth and global civilization.

Methods

European marine protected areas

The analysis focused on MPAs located within European exclusive economic zones (EEZ), including EU member countries, the United Kingdom, Norway, and Iceland. Polygons representing the spatial distribution of MPAs in European seas were acquired from the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA)73. To avoid overestimating the total protected area, overlapping polygons were spatially dissolved. This process resulted in 1890 polygons, which we will refer to as marine protected areas (MPAs) throughout the remainder of this study. MPAs were assigned to one of the six sea regions: Norwegian Sea, North Sea, Baltic Sea, North-East Atlantic Sea, Black Sea, or Mediterranean Sea (Fig. S1).

Species selection and their distribution maps

We assembled a list of commercial species and corresponding catch data per EEZ from the Sea Around Us database (https://www.seaaroundus.org/). Only species designated as minor commercial, commercial, or highly commercial based on FishBase52 status were incorporated into our study. This list was augmented with species categorized as critically endangered, endangered, vulnerable, or nearly threatened on the European Red List (IUCN 2010 European Red List, accessed June 2022). Where a species’ status was absent from The European Red List, we referred to the Global IUCN Red List, which was applicable to 40 species. This resulted in a final list of 398 species (Table S1) composed of 276 commercial species, 100 species with both commercial and conservation statuses, and 22 species that only held a conservation status. Among species with an IUCN status, 19 were critically endangered, 29 endangered, 36 vulnerable, 38 nearly threatened, and 34 data deficient. The taxonomic classes breakdown of all species was: 232 Actinopterygii (58.29%), 103 Chondrichthyes (25.88%), 24 Arthropoda (6.03%), 18 Bivalvia (4.52%), 10 Cephalopoda (2.51%), 6 Gastropoda (1.5%), 3 Echinodermata (0.75%), 1 Petromyzonti (0.25%), 1 Thecostraca (0.25%). Distribution range maps for all species were obtained from IUCN and Aquamaps74.

Climate data

Climate variables at the global scale and with a spatial resolution of 0.25° were produced with the Bio-ORACLE computational pipelines75. The timeframes examined were the contemporary baseline period (2010–2020) and the end-of-century period (2090–2100) under two Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP) scenarios of future climate change: the SSP1–1.9, a low-emission “sustainability” scenario in line with the expectations of the Paris Agreement, and the SSP5–8.5 scenario, representing the “fossil-fueled development” associated with the highest carbon emissions and mitigation challenges. The variables chosen were maximum temperature, average dissolved oxygen, pH, and primary productivity (PP). Data for the baseline period was sourced from Copernicus Marine Service, while the SSP scenarios data was derived from an ensemble75 of several general atmosphere-ocean circulation models (ACCESS-ESM1-5, CanESM5, CESM2-WACCM, CNRM-ESM2-1, GFDL-ESM4, GISS-E2-1-G, IPSL-CM6A-LR, MIROC-ES2L, MPI-ESM1-2-LR, MRI-ESM2-0, UKESM1-0-LL) provided by the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project’s 6th iteration (CMIP).

Climate novelty analysis

Our climate novelty analysis is based on the sigma dissimilarity (σ) methodology described by Mahony et al.76, which uses a modified multivariate standardized Euclidean distance (SED) metric77,78. The modifications include converting SED to Mahalanobis distances and interpreting climate distances as percentiles of the chi distribution. This approach was selected because the application of Mahalanobis distance rescales variables in relation to local intra-annual climate variation (ICV) and reduces variance inflation due to correlations. The chi distribution interpretation accommodates the dimensionality effect, facilitating comparisons between analyses utilizing varying numbers of input variables79,80.

This approach enabled quantifying climate novelty between end-of-century climate conditions (2090–2100) and their nearest present-day climatic counterparts (2010–2020). To calculate sigma dissimilarity for each species, we converted the variables of the baseline and projected periods into anomaly z-scores by subtracting the baseline data (2010–2020) mean ICV at each cell level and subsequently dividing by the baseline data ICV standard deviation81. Then, a principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out on the standardized baseline data, retaining the components that accounted for 99% or more of data variability. This PCA was employed to transform both standardized baseline and projected data. Next, the Mahalanobis distances between each ocean cell of the transformed projected climate data and its nearest equivalent from the transformed baseline climate data pool within the species of interest’s range map were calculated80. This process linked the multivariate climate distance of target locations to the species’ climatic niche, with the closest similar climate reflecting global baseline data ocean cells with a similar climate to the projected climate at target locations. Finally, sigma dissimilarity, a statistical measure of deviation from baseline climates, was calculated by translating Mahalanobis distances using the chi distribution. We modified Mahony et al.76 and categorized σ < 2 as similar climate conditions, 2 < σ < 4 novel climates (the 95th percentile of the baseline climate), and σ > 4 as extremely novel climate (the 99.99th percentile of the baseline climate). Sigma dissimilarity was calculated for all target species in this study, both within each European MPA and within the borders of each six sea regions (without MPA borders). Species and MPAs with σ > 2 are considered at risk in this study, and species and MPAs with σ < 2 are considered not at risk.

Responses