V-ATPase contributes to the cariogenicity of Candida albicans- Streptococcus mutans biofilm

Introduction

Dental caries, a chronic infectious disease occurring in the hard tissue of teeth, has become a major global public health problem because of its high incidence and wide coverage1,2. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study, untreated dental caries in permanent teeth has been the most common disease for the last decade. In 2017, the global prevalence of caries in permanent teeth was 29.4%, affecting up to 2.3 billion people, while caries in deciduous teeth affected 532 million children3,4.

The occurrence and development of dental caries is closely related to the imbalance of dental plaque microbiota. The oral cavity has been considered to possess the second most complex microbiota in human body, only behind the colon. The oral microbiome is highly diverse, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, archaea and protozoa (eHOMD, https://homd.org/), which play important roles in maintaining the homeostasis of oral microenvironment and preventing oral infectious diseases such as dental caries and periodontal disease5,6. Among these microorganisms, S. mutans is recognized as the main cariogenic pathogen. Despite its low relative abundance in the oral cavity, it can gain a competitive advantage when the microbial community become unbalanced due to local microenvironmental changes. It can rapidly ferment carbohydrates to produce acid and synthesize intracellular and extracellular polysaccharides, and promote the adhesion and aggregation of microorganisms on the tooth surface7,8. In recent years, the role of fungi in oral diseases has attracted more and more attention, among which C. albicans is the main fungus related to oral diseases. It usually colonized on the surface of oral mucosa as commensal microbe. Some systemic and local factors such as systemic chronic diseases, immunodeficiency, poor oral hygiene, wearing removable dentures or appliances can increase its detection rate9,10,11. Similar to S. mutans, C. albicans possesses cariogenic abilities such as adhesion, acid production and resistance, and biofilm formation. It can invade the deep dentine through its hyphae, contributing to the progression of dental caries by cross-kingdom interaction with S. mutans.

As common symbiotic microbes in the oral cavity, the interaction of C. albicans and S. mutans plays an important role in the maturation of dental plaque and the progression of dental caries. The colonization of C. albicans reduces the local oxygen level and induces the imbalance of oral microorganisms, making the local environment more suitable for S. mutans. It can colonize on the tooth surface through the building block provided by S. mutans, and its hyphae promotes its adhesion to other bacteria including S. mutans. Then they form a symbiotic biofilm, which help resist against stress from the host and the external environment12,13. In addition, C. albicans can enhance the cariogenicity of S. mutans by increasing the production of extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) and the expression of virulence genes such as gtfB and fabM14. Some animal experiments showed increased incidence and severity of dental caries in rats infected with C. albicans and S. mutans, compared with those infected with a single one15,16. Clinical studies have also shown that the detection rates of C. albicans in early childhood caries and root caries are significantly increased17,18,19.

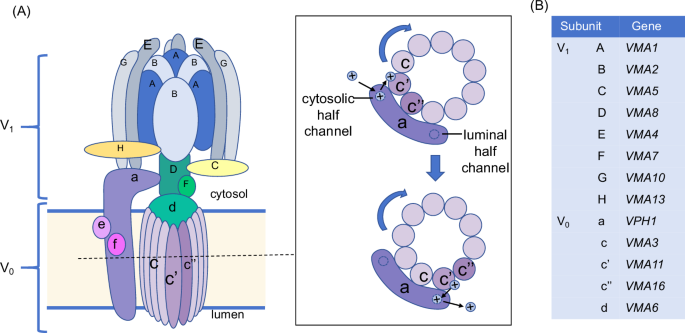

Vacuole is a vital structure for C. albicans to adapt to environmental stress and maintain virulence. Vacuolar proton-translocating ATPase (V-ATPase) is the main proton pump on the vacuolar membrane, responsible for pH homeostasis regulation, stress response, and hyphal growth of C. albicans20. As shown in Fig. 1, V-ATPase is a rotating multi-subunit protein complex. The V1 domain located in the cytoplasm is composed of eight subunits of ABCDEFGH, which is responsible for ATP hydrolysis to provide energy for H+ transport. The V0 domain across the membrane is composed of adef subunits and a “c ring” structure, which provides a transport channel21. Each subunit of V-ATPase is encoded by a specific gene. The V1 A and B encoded by VMA1 and VMA2 constitute a hexamer and participate in ATP binding and hydrolysis22. The c, c’ and c” encoded by VMA3, VMA11 and VMA16 constitute the “c ring”, which is the main site of proton transport. By rotating and combining with the two hemichannels of V0 a, it can transport H+ from cytoplasm to vacuole to maintain the cytoplasmic pH homeostasis and the activities of various degradation enzymes in the vacuole23. The subunits of V0 d, V1 D, and V1 F are encoded by VMA6, VMA7, and VMA8. They constitute the central axis, which rotates with the “c ring” to accomplish proton transport24,25. VMA4-encoded V1 E and VMA5-encoded V1 C play important roles in the connection and stability of V-ATPase26,27. These encoding genes regulate the assembly of all the subunits to guarantee the integrity of V-ATPase structure and function, and to maintain the survival and virulence of C. albicans28,29. Studies have found that inhibition or knockout of these genes in C. albicans can lead to abnormal morphology and function of vacuole, hyphal development defects, and reduced adaptability to environment, which is manifested as attenuated or avirulent in mouse models of systemic candidiasis22,23,24,25,26,27.

A The pattern of V-ATPase structure and proton transportation. B The encoding genes of each subunit.

In recent years, reducing the cariogenicity of the C. albicans–S. mutans biofilm by interfering with its interaction has posed a new idea for the prevention and therapy of dental caries30,31. As an important protein in regulating virulence in C. albicans, V-ATPase is a potential target for the resistance of C. albicans-S. mutans biofilm and the treatment of dental caries. However, there is a lack of studies about the regulating effect of V-ATPase on the C. albicans–S. mutans interaction and the cariogenicity of biofilm.

This study verified the relationship between dental caries and C. albicans and its V-ATPase through the isolation of clinical strains of C. albicans and detection of gene expressions. On this basis, we constructed V-ATPase related gene knockout mutants for VMA3 and VMA4, which had significantly high expressions in caries groups, as well as VMA11, the encoding gene of V0 c’ subunit without homologous protein in human body. The regulating effect of V-ATPase on cariogenicity of C. albicans–S. mutans biofilm and its mechanisms were elucidated through researches in vitro and in vivo. This study is expected to provide basis for seeking potential targets for early ecological prevention and treatment of dental caries.

Results

C. albicans and V-ATPase were closely related to dental caries in children

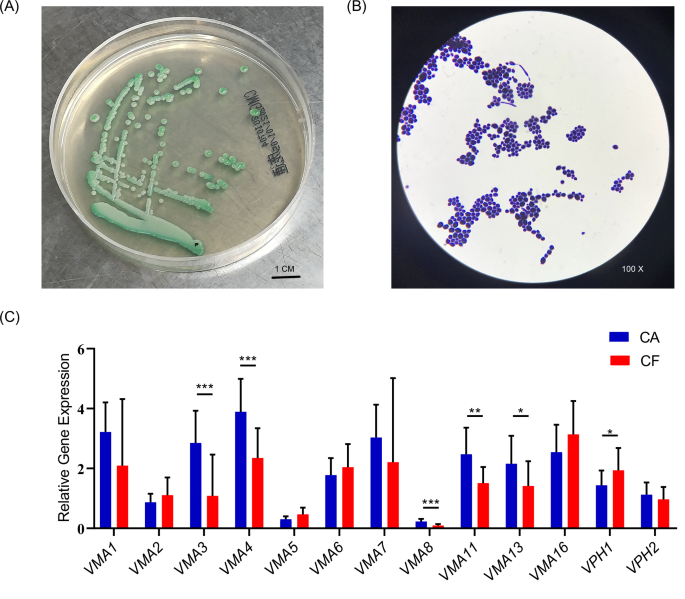

As shown in Table 1, 59 caries-active children and 50 caries-free children were enrolled in this study. C. albicans was detected in 13 samples of group CA and 4 samples of group CF. The detection rate of C. albicans in group CA was 22.03%, significantly higher than that in group CF (8.00%, p < 0.05), suggesting that the colonization of C. albicans may increase the risk of dental caries in children.

Then we isolated clinical strains of C. albicans from caries-active children (Fig. 2A, B), and detected the expression levels of V-ATPase related genes in C. albicans clinical strains were detected by qPCR. As shown in Fig. 2C, six genes showed significant differences between the two groups (P < 0.05). Among them, the expression of VMA3, VMA4, VMA8, VMA11, and VMA13 were significantly higher in group CA, suggesting that these genes may be involved to the cariogenicity of C. albicans.

A Colony morphology of clinical C. albicans strains on selective medium from caries samples. B Cell morphology of clinical C. albicans strains after Gram stain. C V-ATPase related gene expression of C. albicans clinical strains. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

The growth characteristics of C. albicans were regulated by V-ATPase

Based on the results of the gene expressions, we constructed gene knockout mutants for VMA3 and VMA4, which were highly expressed in caries group, as well as VMA11, the encoding gene of V0 c’ subunit without homologous protein in human body, to further study the regulating effect of V-ATPase on the growth of C. albicans and the cariogenicity of C. albicans-S. mutans biofilm. The construction of knockout mutants was shown in Fig. S1.

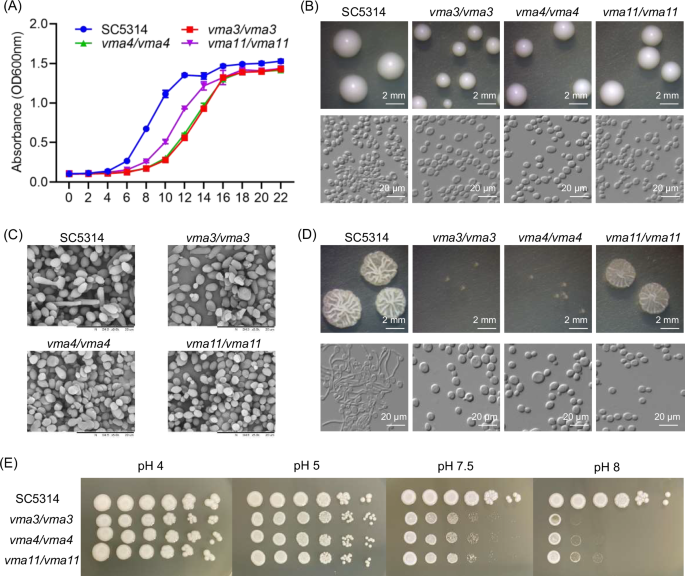

The growth curves of C. albicans WT and V-ATPase gene deletion mutants are shown in Fig. 3A. Compared with the WT, the time for the knockout mutants to reach the logarithmic phase and the stable phase was delayed. Among them, the growth curves of VMA3 and VMA4 knockout mutants almost overlap, and the growth of VMA11 knockout mutants was slightly faster. The results showed that the growth of C. albicans was inhibited after the knockout of V-ATPase related genes.

A Growth curves of different strains. B Morphology of colony and cell incubated on YPD. Green arrow indicates nucleus, red arrow indicates vacuole, and blue arrow indicates hyphae. C Morphology of fungal cells under SEM. Red arrows indicate abnormal shapes. D Morphology of colony and cell incubated on Spider. E Growth on plates with different pH values.

As shown in Fig. 3B, V-ATPase gene deletion mutants showed growth inhibition on YPD medium, with decreased colony size. And the cells of knockout mutants were flat, with different sizes and unclear outline of organelles. The observation under SEM showed that most cells of the WT were round with smooth surfaces, whereas the cells of VMA3/VMA4/VMA11 knockout mutants were abnormally shaped, with different sizes and deformities such as cell shrinkage, rupture, and even exfoliation (Fig. 3C), indicating that VMA3, VMA4, and VMA11 played an important role in the growth and morphology of C. albicans.

The hyphal growth was induced using Spider medium (Fig. 3D). The VMA3/VMA4/VMA11 knockout mutants showed deficiency in hyphal growth, compared with the WT. Among them, and VMA3 and VMA4 knockout mutants showed significantly smaller and smoother colonies. In Spider liquid medium, most cells of the WT could form long and interlaced hyphae, while cells of knockout mutants were all maintained as yeasts, indicating that VMA3, VMA4, and VMA11 were involved in the hyphal growth of C. albicans.

The growth conditions of C. albicans in the medium with different pH values are shown in Fig. 3E. Compared with the WT, the growth of VMA3, VMA4, and VMA11 knockout mutants in acidic environment (pH 4 and pH 5) showed no significant differences, but the growth in alkaline environment (pH 7.5 and pH 8) was significantly inhibited, indicating that V-ATPase genes VMA3, VMA4, and VMA11 were involved in regulating the alkali resistance of C. albicans.

V-ATPase was involved in the morphology of C. albicans-S. mutans biofilm

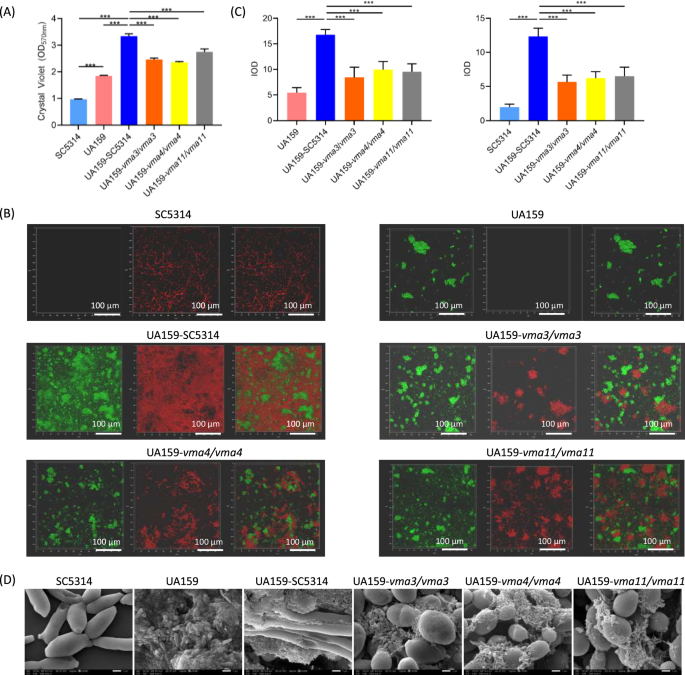

Since V-ATPase affected the growth and morphology of C. albicans, we aimed to study the effect of these changes on the C. albicans–S. mutans dual-species biofilm.

The biofilm biomass was measured by crystal violet assay (Fig. 4A). The VMA3, VMA4, and VMA11 knockout mutants showed reduced ability to form both single-species biofilm and dual-species biofilm with S. mutans (P < 0.001).

A Biomass of single-species and dual-species biofilm. B The structure of biofilm labeled with FISH probes. S. mutans was labeled green, C. albicans was labeled red. C Quantitative analysis of C. albicans and S. mutans. D Morphology of C. albicans-S. mutans biofilm under SEM. The results are based on three independent experiments and represent as mean ± SD. (***p < 0.001).

The spatial distribution of C. albicans and S. mutans in the dual-species biofilm was detected by FISH (Fig. 4B). In the C. albicans WT-S. mutans biofilm, a large number of hyphae formed a network structure and provided a wide range of adhesion sites for S. mutans. The dual-species biofilms of S. mutans and the VMA3, VMA4 and VMA11 knockout mutants were loose, with significantly decreased C. albicans cells and the proportion of hyphae. Quantitative analysis showed decreased number of C. albicans cells in the three gene deletion strains and decreased number of S. mutans cells in VMA3 and VMA4 deletion strains (Fig. 4C, P < 0.01).

In addition, the morphology of biofilm was observed using SEM. As shown in Fig. 4D, compared with the C. albicans WT-S. mutans biofilm, the mixed biofilms of S. mutans and the VMA3, VMA4 and VMA11 knockout mutants showed loose biofilm structures with decreased proportion of hyphae, less tight adhesion between the two species, and decreased extracellular matrix.

V-ATPase affected the EPS production of C. albicans-S. mutans biofilm

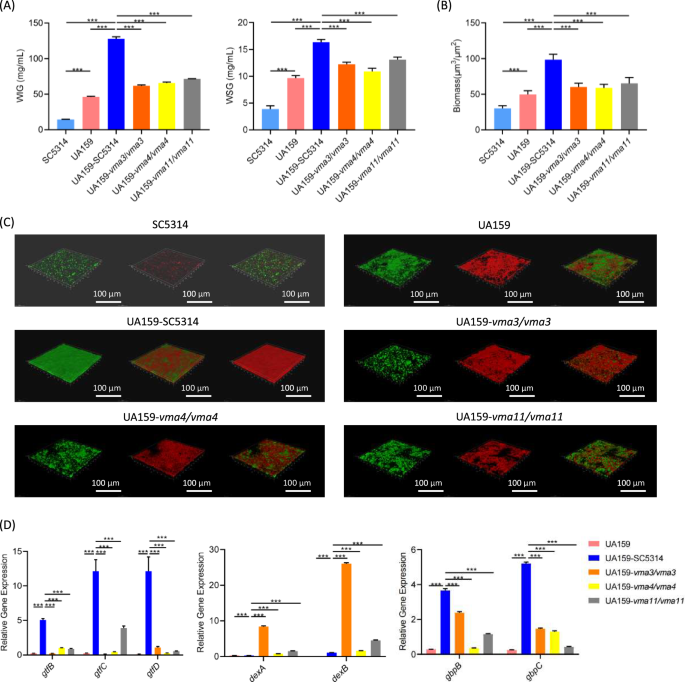

The extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) synthesized by S. mutans constitute one of the major virulence factors of biofilms. Therefore, we further detected the EPS production and composition of C. albicans-S. mutans biofilm by anthrone method. The contents of water-soluble glucan (WSG) and water-insoluble glucan (WIG) in dual-species biofilms are demonstrated in Fig. 5A. Compared with the WT, the VMA3 and VMA4 knockout mutants showed significantly reduced WSG generation (P < 0.001), while no significant difference was found in VMA11 knockout mutants. All the three gene deletion strains showed decreases in the production of WIG (P < 0.001).

A EPS generation assessed by anthrone method. The water-soluble (WSG) and water-insoluble (WIG) polysaccharides were measured respectively. B The biomass of biofilm. C Biofilm structure under CLSM. C. albicans and S. mutans were labeled green, EPS was labeled red. D Gene expressions of S. mutans. The results are based on three independent experiments and represent as mean ± SD. (***p < 0.001).

To visualize EPS distribution, the structures of C. albicans-S. mutans biofilm were observed under CLSM. Quantitative analysis showed significantly decreased biofilm thickness in the dual-species biofilm formed by S. mutans and the V-ATPase gene knockout mutants (Fig. 5B, P < 0.05). As shown in Fig. 5C, in the dual-species biofilm of C. albicans WT-S. mutans, microbes aggregated and surrounded within a matrix of EPS, forming a complex and dense biofilm structure. However, the number of microbes and the EPS generation decreased in the dual-species biofilm of S. mutans and the V-ATPase gene knockout mutants, manifesting as scattered blocks and loose biofilm structures.

To explain the reason for the EPS decrease, we detected the gene expressions of S. mutans by qPCR. As shown in Fig. 5D, the expression levels of EPS synthesis-related genes gtfB/gtfC/gtfD and adhesion-related genes gbpB/gbpC decreased after co-culture with VMA3/VMA4/VMA11 knockout mutants, while the expression of EPS decomposition genes dexA and dexB were significantly up-regulated (P < 0.01).

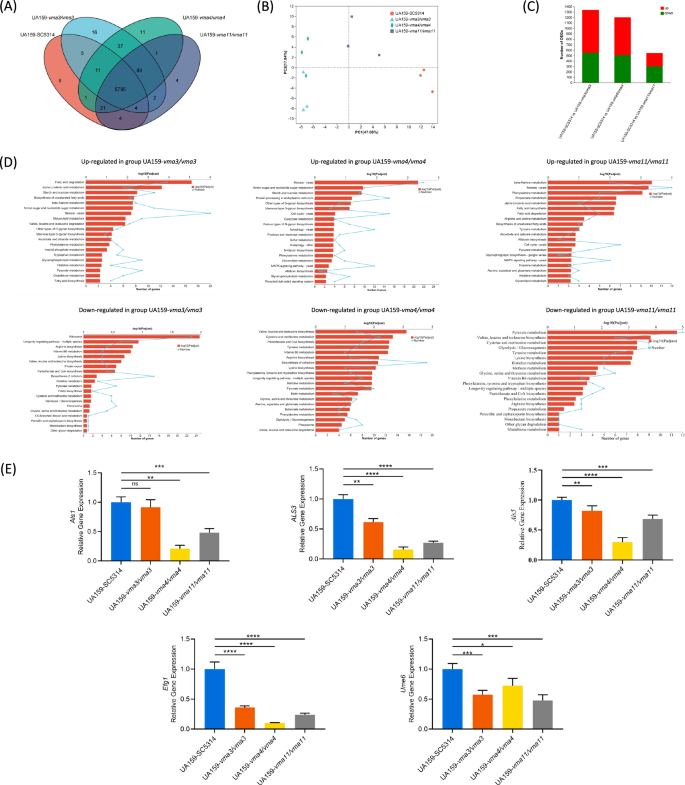

V-ATPase regulated the gene expressions of C. albicans in dual-species biofilm

Transcriptome sequencing of C. albicans in dual-species biofilm detected 5849, 5959, 5966, and 5920 genes in the WT and VMA3/VMA4/VMA11 knockout mutants respectively, of which 5795 genes were common in the four groups (Fig. 6A). Principal component analysis (PCA) showed that gene expression in the VMA3 and VMA4 knockout groups was generally similar, separated from neither the WT nor VMA11 knockout group (Fig. 6B). Compared with the WT, 1339 (787 up-regulated, 552 down regulated), 1199 (692 up-regulated, 507 down regulated), and 548 (248 up-regulated, 300 down regulated) differentially expressed genes were detected in the VMA3, VMA4, and VMA11 knockouts respectively (Fig. 6C). According to KEGG pathway annotation and enrichment analysis, the up-regulated genes were mainly involved in meiosis, while the down-regulated genes were mainly involved in pyruvate and amino acid metabolism, ribosome, and biosynthesis of cofactors (Fig. 6D). Consistently, we also verified the hyphal formation and adhere related genes by RT-qPCR, and the results showed that the expression of Als1,Als3, Als5, Efg1 and Ume6 genes in the knockout mutant group was down-regulated (Fig. 6E).

A Venn diagram. B PCA analysis. C Differentially expressed genes. D KEGG pathway annotation and enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes. E Hyphal formation and adhere genes expressions of C. albicans. The results are based on three independent experiments and represent as mean ± SD. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ns, not significant).

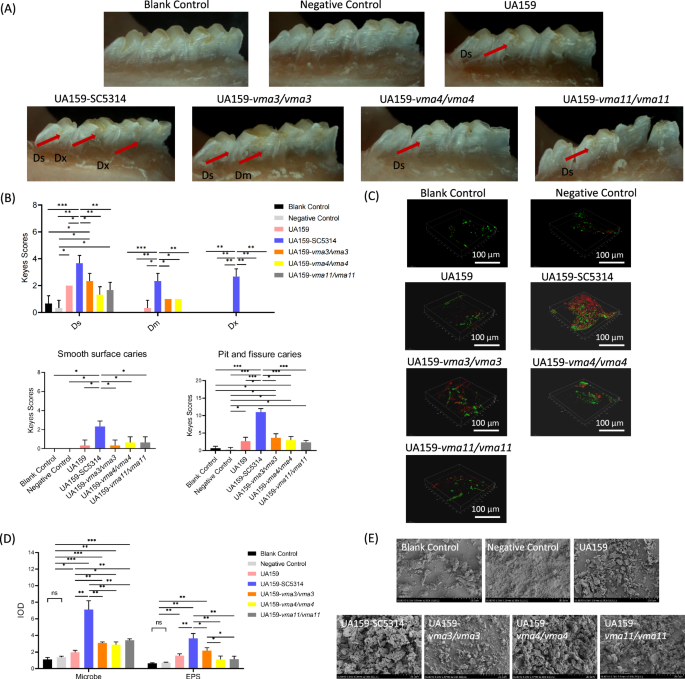

The cariogenicity of C. albicans–S. mutans biofilm was influenced by V-ATPase

To further confirm the effect of V-ATPase on the cariogenicity of C. albicans-S. mutans biofilm in vivo, the dental caries on the mandibular molars of rats were observed and assessed by Keyes’ method (Fig. 7A, B). The blank control and the negative control group showed no smooth surface caries and no more than one pit and fissure caries. Demineralization and shallow caries could be found in the S. mutans single-species group and dual-species groups with C. albicans VMA3/VMA4/VMA11 knockout mutants. The number and severity of caries lesions in the S. mutans–C. albicans WT group were higher than those in other groups (P < 0.05).

A Stereoscopic observation of caries. B Keyes score of caries at different sites. C Structure of dental plaque under CLSM. D Quantitative analysis of microbes and EPS in dental plaque. E Morphology of dental plaque under SEM.

The structures of dental plaque were observed under CLSM and quantitatively analyzed (Fig. 7C, D). In the positive control (S. mutans–C. albicans WT) group, the dental plaque almost covered the entire tooth surface, with a large number of microbes and EPS. The coverage and thickness of dental plaques and the number of microbes and EPS significantly decreased in the S. mutans single-species group and dual-species groups with gene deletion strains (P < 0.05).

The morphology of dental plaque near the gingival margin on the buccal side of the molars was observed under SEM (Fig. 7E). A thick and dense biofilm with a large number of extracellular matrix and hyphae was found on the tooth surface of the S. mutans–C. albicans WT group. The dental plaque was scattered in the blank control and the negative control group. The thickness and density of dental plaque in the S. mutans single-species group and dual-species groups with gene deletion strains were lower than those of the S. mutans–C. albicans WT group.

Discussion

C. albicans and S. mutans are common symbiotic microbes and opportunistic pathogens in the oral cavity. They can affect the oral microbial balance by interacting with each other, playing critical roles in the occurrence and development of dental caries32,33. C. albicans can be detected in 30–60% peoples’ oral cavity, mostly colonized on the mucosal surface10. In this study, samples were collected from supragingival plaque, the site most closely related with dental caries. Although the detection rate of C. albicans was lower than that of oral mucosa and saliva, it was significantly higher in children with dental caries than that in healthy controls. The results confirmed that C. albicans was closely related to caries activity in children, thus it should be taken into consideration of early risk assessment of caries in children.

Because of the relationship between C. albicans and dental caries, it is of great significance in clinical prevention and treatment to study the cariogenic mechanism of C. albicans. V-ATPase is an important protein of C. albicans in environmental stress adaption, hyphal development, and virulence maintenance, which is considered as a potential target for resisting C. albicans infection34. This study isolated C. albicans from dental plaque of children with different caries conditions and analyzed the expression levels of V-ATPase related genes in the clinical isolates. The results showed that VMA3, VMA4, VMA8, VMA11, and VMA13 may be involved in regulating the cariogenicity of C. albicans. Among these genes, VMA3 and VMA4 showed the highest expressions and the most significant differences between caries-active and caries-free group, while VMA11 encoded V0 c’ that has no homologous protein in human body, showing application potential as an anti-biofilm target. Therefore, we constructed VMA3, VMA4, and VMA11 gene knockout mutants to further study the regulating effects of V-ATPase on the growth characteristics of C. albicans and the cariogenicity of C. albicans–S. mutans biofilm and its mechanisms.

VMA3, VMA4, and VMA11 knockout mutants showed significant inhibition in growth and hyphal formation, and destruction of cell wall integrity. These results were consistent with previous studies, which verified the important role of V-ATPase in the growth and morphology of C. albicans22,23,24,25,26,27. C. albicans mostly grows in a yeast form in acidic environment (pH<6.5), and when exposed to neutral or alkaline environment (pH > 6.5), it shifts to a hyphal pathogenic form35. The pH of human oral mucosa and saliva is 6.0 to 7.4, so C. albicans can be induced to hyphal form under appropriate conditions, making it easier to adhere to the tooth surface, interact with bacteria, and form dental plaque. In this study, VMA3, VMA4, and VMA11 knockout mutants showed poor tolerance to alkaline environment, which may influence the colonization and hyphal development of C. albicans in the oral cavity, and further affect the adhesion and biofilm formation.

Dental plaque is an archetypical biofilm containing microbial cells and extracellular matrix. The extracellular matrix is composed of proteins and polysaccharides, playing roles in the protection, nutrition and adhesion of microbial cells embedded in extracellular matrix. In this study, the ability of VMA3, VMA4, and VMA11 knockout mutants to form C. albicans-S. mutans dual-species biofilm was significantly reduced, with decreased amounts of microbial cells and polysaccharides generation. C. albicans could not provide adhering sites to S. mutans by hyphal growth, resulting in loose biofilm structure. Consistently, in vivo experiments found that the coverage and thickness of dental plaque, the number of microbes and EPS, and the cariogenicity in rats in the group of VMA3, VMA4, and VMA11 knockout mutants were significantly reduced compared with the positive control group. These results suggested that C. albicans could promote the adhesion and colonization of microbes on the tooth surface, and improve the cariogenicity of the biofilm. VMA3, VMA4, and VMA11 were involved in these processes, indicating that C. albicans V-ATPase played an important role in regulating cariogenicity.

The cariogenicity of S. mutans is closely related to its ability of adhesion and EPS generation. The glucosyltransferases encoded by gtfB, gtfC, and gtfD are the key regulating factors for EPS generation36,37,38, and the glucan binding proteins encoded by gbpB and gbpC mediate the adhesion of S. mutans to glucan39,40,41. However, the dextranases encoded by dexA and dexB can hydrolyze glucan and destroy its binding sites, reducing the adhesion ability of S. mutans42,43. They also contributes to bacterial metabolism for energy storage and modifying glucans for their co-adhesion property42,44. This study detected the gene expressions of S. mutans in the dual-species biofilms, showing that the expressions of dexA and dexB were significantly up-regulated after the knockout of VMA3, VMA4, and VMA11. By combining the results with the observation of biofilm structure and the detection of EPS, the decrease of EPS production in the mixed biofilm after the knockout of VMA3, VMA4, and VMA11 was due to the reduced number of microbes and the increased expressions of the EPS degradation genes, which regulated glucose metabolism and structural features of the EPS.

The gene expressions of C. albicans in mixed biofilm were detected by transcriptome sequencing. The knockout of VMA3, VMA4, and VMA11 interfered with the metabolism of various amino acids, fatty acids, and sugars, as well as the composition and function of ribosomes, mitochondria, and other organelles, leading to growth inhibition, damage, and death of fungal cells. Some genes involved in cell composition and meiosis were up-regulated, attempting to resist the internal and external stress. However, these genes failed to prevent the cell damage. Finally, the survival and metabolic activity of C. albicans were affected, leading to reduced abilities of C. albicans-S. mutans dual-species biofilm formation and polysaccharide utilization. Each stage of biofilm formation is regulated by related genes, in which adhesion and mycelia-related genes play an important role in the whole process. Agglutinin-like sequence (ALS) family genes are important adhesion related genes in C. albicans, encoding highly similar cell surface glycoproteins and playing a key role in adhesion, biofilm formation and primary invasion45,46. Studies have shown that the glycosyltransferase GtfB secreted by S. mutans can bind to different sites on the surface of the cell wall of C. albicans, indicating that the fungal cell wall component ALS participates in the co-aggregation between C. albicans and S. mutans, and enhances the formation of biofilms of the two strains47. Other studies have shown that the biofilm formation ability of ALS gene knockout mutants is significantly reduced. The fungal APSES protein family plays an important role in regulating morphological transformation, among which Efg1 (enhanced filamentous growth 1) is considered to be the most important transcription factor of C. albicans morphological transformation, participating in the cAMP-PKA signaling pathway. Regulates the response of C. albicans to specific environmental stimuli and the formation of various specific cell phenotypes48. The mycelia-specific gene Ume6 is necessary for mycelia elongation and regulates the level and duration of mycelia-specific transcription. The mycelia-inducing conditions in the surrounding environment maintain mycelia elongation and sustainable development by stably activating the transcription factor Ume649. These results indicated that the mutant strains could significantly down-regulate the expression of these genes, thus affecting the whole process of biofilm formation from the early stage of biofilm development.

The c ring structure of V-ATPase V0 domain is the main site of proton transport, which is mainly composed of eight c subunits, one c’ subunit and one c” subunit. Therefore, the c subunit encoding gene VMA3 plays a crucial role in the activity of V-ATPase. In our study, the inhibition in cell growth and hyphal development of C. albicans, the reduced biomass and EPS generation of C. albicans-S. mutans biofilm, and the reduced cariogenicity of biofilms were more obvious in the VMA3 deletion strain than those in the VMA11 deletion strain. The VMA4 encoded V1 E is located at the periphery of the AB subunit hexamer, playing roles in the connection of V1 and V0 domains and the stability of V-ATPase, to ensure its correct assembly and function. Therefore, similar to VMA3 deletion strain, the phenotype of C. albicans and C. albicans-S. mutans biofilm was also seriously affected after the knockout of VMA4. These results suggested that subunits of V-ATPase jointly maintain the integrity of its structure and function, and participate in regulating cariogenicity of biofilms.

In conclusion, we hypothesized that V-ATPase impacted the survival and virulence of C. albicans by regulating its ion homeostasis and hypha development, and then promoted the adhesion to S. mutans and the biofilm formation. With the changing biofilm microenvironment, the metabolic activities of microbial cells were regulated, including the EPS synthesis and decomposition of S. mutans. As the result, the cariogenesis of biofilm was affected through glycoacid metabolic reprogramming.

As the C. albicans–S. mutans interaction play an important role in caries progression, it has great potential for the prevention and treatment of dental caries to reduce the cariogenicity of C. albicans–S. mutans biofilm by interfering with their interaction. Our study revealed the important regulatory effects of V-ATPase on the biofilm cariogenicity and its potential mechanisms through isolation and gene detection of C. albicans clinical strains, and experiments in vitro and in vivo based on the knockout of V-ATPase related genes. The results provided theoretical and experimental basis for seeking new strategy of caries ecological prevention and treatment targeting V-ATPase. Considering that the V0 c’ subunit encoded by VMA11 had no homologous protein in human body, it may be an ideal target for V-ATPase inhibitors and antifungal drugs. More attempts can be made to interfere cross-kingdom biofilms by developing new molecular targeted compounds and nanomaterials.

Materials and methods

Strains and culture conditions

The wild type strains C. albicans SC5314 and S. mutans UA159 were commercially obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The clinical strains of C. albicans were isolated from dental plaque using CHROMagar Candida medium and identified by PCR using the universal primers ITS1 (5’-CCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG -3) and ITS4 (5’- TCCTCCGCTTA TTGATATGC -3’). The knockout mutants of C. albicans V-ATPase encoding genes VMA3, VMA4, and VMA11 were constructed by fusion PCR strategies50. Plasmids pSN52 and pSN40 were used for amplification of HIS1 and LEU2 markers, respectively. C. albicans genomic DNA was used for amplification of the 5’- and 3’- flanking fragments of the corresponding genes. The HIS1 and LEU2 markers flanked by VMA3/4/11 5’- and 3’- fragments were amplified with fusion PCR. The PCR products of the HIS1 and LEU2 markers were sequentially transformed into C. albicans WT, generating the VMA3/4/11 gene deletion mutants. Primers used for PCR are listed in Table S1.

C. albicans strains were routinely cultured in YPD medium (20 g/L glucose, 20 g/L peptone, and 10 g/L yeast extract). Spider medium (10 g/L nutrient broth, 10 g/L mannitol, and 2.6207 g/L K2HPO4•3H2O) was used to assess hyphal formation. Brain-heart infusion (BHI) medium was used for routine growth of S. mutans. Solid medium was supplemented with 2% agar. C. albicans was incubated at 30 °C (for routine culture) or 37 °C (for hyphal induction) with shaking at 200 rpm aerobically, while S. mutans was incubated at 37 °C anaerobically (90% N2, 5% H2, 5% CO2).

YNBB medium (0.67% YNB, 75 mM Na2HPO4, 75 mM NaH2PO4, 2.5 mM N-acetylglucosamine, 0.2% casamino acids, and 0.5% sucrose) was used for co-culture of S. mutans and C. albicans. Cells were harvested at mid-exponential phase by centrifugation. The density of S. mutans was adjusted to 1 × 106 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL and C. albicans to 1 × 104 cells/mL. Observations of dual-species biofilm were performed after 24 h incubation at 37 °C aerobically.

Clinical sample collection

Children aged between 3 and 12 were recruited from the Affiliated Hospital of Stomatology of Chongqing Medical University in Chongqing, China (ethical approval number: CQHS-IRB-2022-126). All of the participants received a comprehensive oral examination based on the standards of the World Health Organization “Oral health surveys: basic methods-5th ed”51. Children with dental caries (DMFT or dmft >0) were enrolled into the caries-active group (group CA), and healthy control individuals matched for age and gender to them were enrolled into the caries-free group (group CF). Subjects were excluded if they (i) had other bacterial or fungal infection oral disease, (ii) had oral mucosal disease, (iii) had gingivitis and periodontal disease, (iv) had systemic or congenital disease, (v) had received antibiotics within 3 months, or (vi) were undergoing orthodontic treatment. Parents or guardians of the participants were sufficiently informed about the aims of the research and voluntarily signed an informed consent according to the recommendations of the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical University.

Participants were required to avoid eating, drinking, or tooth brushing 2 h before sample collection, and rinse their mouth with sterile saline. Supragingival plaque was scraped by a sterile Gracey curette, pooled into a sterile microcentrifuge tube on ice, and immediately stored at −80 °C until further processing.

Growth curve assay

C. albicans cells of the WT strain and V-ATPase gene deletion mutants were incubated in YPD liquid medium overnight to stationary phase, and then transferred to fresh YPD liquid with an initial concentration of 5000 cells/mL. The cells were incubated at 30 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. Cell densities were detected at different time points. Three independent repeats were performed.

Spot dilution assay

Overnight cultures of C. albicans in YPD liquid were tenfold serially diluted in distilled water at final concentrations ranging from 1 × 108 to 1 × 103 cells/mL. Subsequently, 2 μL of each dilution was spotted onto YPD plates with different pH values (pH 4, 5, 7.5, and 8). The growth conditions of the colonies were observed after 3 d of incubation at 37 °C.

Morphological changes of C. albicans cells and C. albicans–S. mutans biofilm

The C. albicans cells harvested at mid-exponential phase and the C. albicans–S. mutans biofilms after 24 h incubation in YNBB were fixed with 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde for 2 h at 4 °C. The fixed samples were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), dehydrated in a series of ethanol solutions (50, 75, and 90% for 10 min and then absolute alcohol for 10 min twice), and subsequently treated with a series of tert-Butanol solutions (50, 75, and 90% for 10 min and then absolute tert-Butanol for 10 min twice). The samples were freeze-dried, coated with a thin layer of gold-palladium, and observed under a scanning electron microscope (TM-3000, Hitachi, Japan).

Biofilm biomass assay by crystal violet staining

After being incubated in 96-well microtiter plate with YNBB as medium for 24 h, the biofilm was gently washed with PBS and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 15 min. Then, the stained biofilm was washed again with PBS and the crystal violet was solubilize with 33% glacial acetic acid. The optical density was measured at 595 nm using a microplate reader (Cytation 3, BioTek, USA).

Exopolysaccharides assessment by anthrone method

The exopolysaccharides generation was assessed by anthrone method52. After being incubated in 24-well microtiter plate for 24 h, biofilms were harvested by scraping and vortexing in PBS buffer. The supernatant and sediment were harvested respectively by centrifugation (4000 rpm, for 15 min, at 4 °C).

The supernatant containing water-soluble polysaccharides (WSG) was filtered through a 0.22 µm filter, and 20% trichloroacetic acid was added and the mixture was placed at 4 °C for 2 h. The solution was centrifuged (4000 rpm) for 30 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected for WSG measurement.

The sediment was resuspended in 1 mL of 1 M NaOH and placed at 37 °C for 3 h with shaking (200 rpm). After centrifugation (4000 rpm) for 15 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was collected for WIG measurement.

Then, 600 μL of anthrone reagent was added to 200 μL of supernatant, and the mixtures were heated at 95 °C for 10 min. The absorbance of each sample at 620 nm was monitored on a microplate reader. The standard curve was prepared with a dextran standard using various concentrations, and the corresponding polysaccharide concentration was calculated according to the standard curve.

Structural analysis of mixed biofilm by CLSM

The three-dimensional structures of the biofilms were observed under a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) (TCS SP8, Leica, Germany).

To visualize EPS distribution, 1 μM Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen, USA) were added into mix suspensions in confocal dishes before biofilm incubation. After incubation at 37 °C for 24 h in the dark, the microbe cells were labeled with 2.5 μM SYTO9 (Invitrogen, USA).

To visualize the distribution of C. albicans and S. mutans, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed to label the two species with species-specific probes (Table S1)53. The mix suspensions were incubated in confocal dishes at 37 °C for 24 h in the dark for biofilm formation. After washing with PBS, 4% paraformaldehyde solution was added to fix the biofilms at 4 °C for 10 h. The fixed biofilms were washed and dried at 46 °C for 15 min, incubated in lysis buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl, 50 mM EDTA, 30 g/L lysozyme) at 37 °C for 20 min, dehydrated in a series of ethanol solutions (50, 80, and 96% for 3 min respectively), and dried at 46 °C for 10 min. The FISH probes were dissolved and mixed with hybridization buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 0.9 M NaCl, 20% formamide, 0.01% SDS), and then added to the samples. After incubated at 46 °C for 90 min in the dark, the samples were treated with washing buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 215 mM NaCl, 0.01% SDS) and incubated at 48 °C for 15 min in the dark.

The biofilm samples were observed by CLSM with a 20× objective lens. The 3D images were reconstructed by Application Suite X (LAS X) software (Leica, Germany), and quantitative analysis of fluorescence was performed using ImageJ.

Expression analysis using qRT-PCR

C. albicans cells were harvested at mid-exponential phase by centrifugation. Biofilms were harvested by scraping after incubation in 6-well microtiter plate with YNBB as medium for 24 h. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions, and cDNA was prepared using RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Quantitative reverse real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed in a Bio-Rad CFX96 real-time PCR detection system using SYBR Green qPCR mix (TOYOBO, Japan). The expression levels of each experimental sample were normalized to those of ACT1 (for C. albicans) or gyrA (for S. mutans). Primers used in this analysis are listed in Table S1.

RNA-Seq analysis

Biofilms were harvested by scraping after incubation in 6-well microtiter plate with YNBB as medium for 24 h, and total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent. The RNA concentration was assessed by Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, USA) and RNA quality was determined by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. RNA-seq transcriptome library was prepared using TruSeqTM RNA sample preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA), and the library products were sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq Xten. The reads were separately aligned to reference genome (C. albicans SC5314) for analyses of differential expression and functional enrichment. The raw reads were deposited into the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (Accession Number: SRP488423).

To identify DEGs (differential expression genes) between different samples, the expression level of each transcript was calculated according to the transcripts per million reads (TPM) method. RSEM (http://deweylab.biostat.wisc.edu/rsem/)54 was used to quantify gene abundances. Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq255 with FDR < 0.05 & |log2FC | ≥1 was considered to be significantly DEGs. The GO functional enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis were carried out by Goatools (https://github.com/tanghaibao/Goatools) and KOBAS (http://kobas.cbi.pku.edu.cn/home.do)56 to identify GO terms and metabolic pathways DEGs significantly enriched in.

Cariogenicity of biofilms in vivo

Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were used to investigate the effect of V-ATPase on the cariogenicity of dual-species biofilms in vivo. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical University (ethical approval number: CQHS-IRB-2022-066). SD rats (male, aged 4 weeks) were randomly divided into 7 groups (n = 5 per group), including (i) blank control, (ii) negative control (YNBB medium), (iii) S. mutans WT, (iv) C. albicans WT- S. mutans WT, (v) C. albicans vma3/vma3– S. mutans WT, (vi) C. albicans vma4/vma4– S. mutans WT, and (vii) C. albicans vma11/vma11– S. mutans WT.

C. albicans and S. mutans cells were harvested at mid-exponential phase and resuspended in YNBB medium with the concentration of S. mutans adjusted to 1 × 109 CFU/mL and C. albicans to 1 × 107 cells/mL. Then 200 μL suspensions were orally infected to the mandibular molar area of rats using a cotton ball, daily for 10 days. All rats received cariogenic Diet 2000 and drinking water containing 5% sucrose, and animals were sacrificed under inhalation anesthesia 4 weeks after initial injection.

The smooth surface caries and sulcal caries on the molars were assessed by Keyes’ procedure57. The three-dimensional structure and the surface morphology of dental plaque biofilm were observed by CLSM and SEM, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Three independent experiments were performed for all in vitro analyses, and five parallels were set for each group in studies in vivo. The quantitative results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0, GraphPad, USA). After test for homogeneity of variance, one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s t test were performed to compare differences between multiple groups. Detection rates of C. albicans in dental plaque from caries-active and caries-free children were analyzed with chi-squared test. The expressions of V-ATPase related genes in clinical isolated strains were analyzed with student’s t-test. Differences were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05.

Responses