Value of clinical review for AI-guided deep vein thrombosis diagnosis with ultrasound imaging by non-expert operators

Introduction

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) confers a significant global burden of disease, with a yearly incidence of 50–150 cases per 100,0001. Its clinical consequences range from pulmonary embolism to post-thrombotic syndrome, with significant morbidity and mortality1,2. Ultrasound allows for accurate, rapid, and accessible DVT detection, particularly venous compression point of care ultrasound (POCUS). Sensitivities and specificities vary across operators and interpreters, but are reported to be approximately 90%3,4.

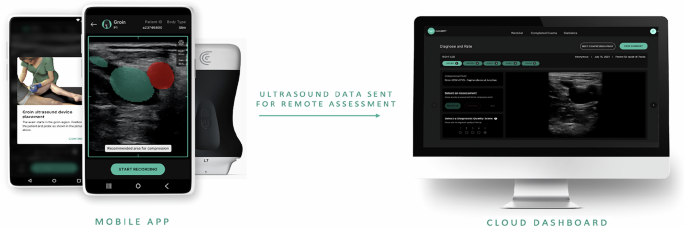

Ultrasound technologies have potential to benefit from the integration of Artificial intelligence (AI)5. One such application is the ThinkSono Guidance System (ThinkSono GmbH), an AI-based guidance platform for venous ultrasound which allows non-ultrasound trained providers to perform lower extremity venous compression ultrasound. Coupled with a clinician image reviewer, this system allows for DVT detection (Fig. 1). What remains to be clarified, however, is the real-world effectiveness of such systems, the factors influencing their performance, and their ability to benefit patients and providers with a level of diagnostic precision equalling the current standard of care. We conduct retrospective analyses of a database comprising ultrasound images and patient data acquired using this AI guidance system. The aim is to comprehensively assess the system’s performance across a variety of reviewers and statistical methods, simulating diverse clinical workflows to evaluate its effectiveness in real-world conditions.

A cloud dashboard for remote image review (right). The guidance app guides the operator to perform a compression ultrasound scan for review by a qualified clinician using the cloud dashboard.

This analysis focuses on AI guidance that includes a “qualified clinician review.” This approach consistently offers the highest levels of accuracy and safety in prior testing, and received regulatory approval (CE Class IIb under EU MDR, EUDAMED DE-MF-000034914)6.

Methods

Study design and data

The data originates from a multicentre, prospective, single-arm, double-blind pilot study specifically designed to evaluate the accuracy of AI-guided ultrasound imaging for DVT diagnosis7. Conducted across 11 UK hospitals, the data collection was embedded within the routine DVT diagnostic services of each participating institution. Eligible patients were those referred with symptoms suggestive of DVT, aged 18 years or older, capable of providing informed consent, and requiring an ultrasound scan based on standard pre-test probability scores (e.g., Wells’ score). Exclusion criteria were strictly enforced and included pregnancy beyond 12 weeks, and a prior radiologically confirmed DVT in the symptomatic leg. The data collection process was aligned with the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) guidelines and received ethical approval from the East of Scotland Research Ethics Service (REC reference: 21/ES/0070)8.

To conduct our analysis, we evaluated data from a total of 381 patients. This cohort included 294 participants with suspected proximal DVT, 15 patients with distal DVT (distal to the popliteal vein), 10 patients who had protocol deviations (e.g., a D-Dimer test could not be performed), and 62 patients who were recruited before a minor adjustment was made to the smartphone application, which did not impact data acquisition7. These scans, along with detailed patient information, were collected between December 2021 and February 2023 across the 11 NHS sites. Each scan underwent independent review by five UK radiologists, whose evaluations of compressibility status and image quality were systematically recorded in the database.

In this study, in addition to the existing UK radiologist interpretations, each scan in the database was also reviewed by five independent American Emergency Medicine physicians certified in interpreting POCUS images with 4–19 years of experience (EM POCUS reviewers). Each reviewer rated the quality of scan cine loops per the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) image quality scale, scoring them from 1 to 59. A score of ≥3 constitutes adequate image quality (Table 1), and was interpreted as compressible (indicating no DVT), incompressible (indicating DVT present), or indeterminate (e.g., incomplete compression). A score of < 3 is considered inadequate image quality and considered an indeterminate diagnosis.

AI guidance system

The evaluated guidance system (ThinkSono Guidance) is a software guiding non-expert users to conduct a two-point compression ultrasound (i.e. common femoral and popliteal veins) to obtain diagnostic-quality images that can be used to diagnose DVT6. The system consists of a software application (app) installed on a smartphone and a portable ultrasound device, in this case the Clarius L7 HD (Clarius Mobile Health Corp). Users need no prior ultrasound or specialised technology experience, but undergo a one-hour training.

When scanning a patient, the user connects the smartphone and the probe through the application and enters basic patient information (ID number, height/weight, etc). The user is then directed to place the probe on the patient’s leg. The software detects the site and position of the probe, directs the operator to move the probe to the required scanning region, and then confirms correct probe positioning. The operator is guided to compress the target vein several times, receiving real-time feedback on compression location, timing, and probe positioning. Once the software confirms acquisition of sufficient and appropriate data, the operator is directed to proceed to subsequent compression point(s). The entire process typically takes under ten minutes.

Statistical analyses

Our primary endpoints were the sensitivity of the guidance system with qualified clinician review and the number of standard, expert-led ultrasound scans avoided. The sensitivity primary endpoint cut-off was 90% sensitivity relative to duplex ultrasound. Our secondary endpoints included specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), diagnostic image quality ACEP score, reviewer inter-observer agreement on image quality, and compressibility assessment. The inter-observer agreement is measured as the mean of the pair-wise Cohen’s kappa.

Additionally, we estimated the number of expert-led duplex scans avoided by use of the AI guidance system10. This analysis compares the number of guidance system exams negative for DVT to the total number of AI guidance exams. This measure is designed to assess the economic and logistic benefits of the guidance system.

The cohort was analysed through the bootstrapping method for each of the two reviewer groups, in which one reviewer’s interpretation for each group was chosen at random for each scan11. Bootstrapping is a non-parametric numerical method to approximate the true distribution without explicitly assuming normality, which is particularly useful in scenarios like ours where multiple raters per sample need to be combined. The process of randomly sampling one out of five reviews and computing diagnostic outcome measures was repeated 500 times to simulate clinical practice, with either one remote reviewer (Table 2b) or an additional second reader (Table 2c).

Bootstrapping’s effectiveness in this context is supported by the law of large numbers, suggesting that the calculated mean or other statistics from the bootstrap samples will converge to the true population parameter12. This is appropriate for the investigated data, with a limited sample size and a non-normal label distribution. Bootstrapping inherently mitigates overfitting to the idiosyncrasies of the original dataset, thus providing more generalised performance estimates. If the sampled remote reviewer interpretation for a given scan was indeterminate, that scan was excluded from computing the diagnostic outcome measures in this bootstrapping iteration, ensuring that only reliable data influenced the outcomes. Thus, sensitivity and specificity are computed as follows:

The number of confirmed DVTs is defined as the number of all patients in the dataset for which the local imaging specialist scan reports the presence of a DVT. The number of false negatives is defined as all outcomes rated as compressible by the reviewer which are confirmed as DVT by the local imaging specialist scan. The number of true negatives is defined as all outcomes rates as compressible by the reviewer which are not confirmed as DVT by the local imaging specialist scan. And the number of false positives is defined as all outcomes rates as incompressible by the reviewer which are not confirmed as DVT by the local imaging specialist scan. Indeterminate outcomes are not counted.

Note that, compared to Curry et al. we compute the overall system sensitivity. This means if a reviewer assesses a scan with a DVT as indeterminate, that DVT should still be considered towards the overall number of DVTs in the dataset, as the patient will be triaged correctly. Curry et al. compute sensitivity on the remaining number of DVTs only, i.e.

We also performed analyses using the bootstrapping approach, but using one other reviewer for each group chosen at random as a 2nd reader (i.e., a random pair sampled from the group of reviewers had to agree to include or exclude a DVT). If the 2nd reader agreed with the original bootstrapping diagnosis for a scan, then it was confirmed. If they disagreed, then the scan was considered indeterminate.

Independent of the bootstrapping analysis, we also applied a majority voting system, described in a prior publication6. Briefly, if at least three reviewers agree on a determination (compressible, incompressible, or indeterminate), then this result is accepted. In any case where there are not at least 3 reviewers in agreement (e.g., 2 compressible, 2 incompressible, 1 indeterminate) the exam is labelled as “indeterminate.”

Analysis techniques are summarised in Table 2. The images for the cohort were reviewed by each of the two reviewer groups, and these interpretations were analysed via majority voting, bootstrapping, and bootstrapping with a 2nd reader. Each analysis is performed for both review panels. This leads to a total of 6 analyses (see Tables 3 and 4). For all analysis groups, ACEP scores were calculated using the same method as the diagnostic results (e.g. bootstrapping applied to both the interpretations and the ACEP scores).

Data are reported using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and values with percentage of the relevant population for discrete variables. Wells’ scores were divided into low (<1), moderate (1–2), and high (>2) categories. Descriptive and continuous values were compared using t-tests or Fischer’s exact testing. P-values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Python v3.10.4 with the SciPy (http://scipy.org/) library v1.13.0.

Results

Patient demographics and Wells score information are shown in Table 5. Nearly half of the cohort was female, mean age was 63, and mean BMI was 31. Most patients had a moderate Wells’ score, and mean d-dimers were 2000 ng/mL FEU. Analysis results, stratified by type of analysis, are summarised in Tables 3 and 4. Eighty percent (n = 304) of all scans received an ACEP image quality score ≥3.

Radiology reviewers’ sensitivity ranged from 90%–95%, specificity from 74%–84%, NPV from 98%–99%, PPV from 30%–42%, and sonographer performed ultrasounds avoided from 39%–50% (Table 3). Inter-observer agreement for adequate image quality was 0.15 and for compressibility assessments was 0.61 (Table 6). EM POCUS reviewers had higher performance metrics, apart from ultrasounds avoided. Sensitivity ranged from 95%–98%, specificity from 97%–100%, NPV was 99%, PPV from 81%–100%, and ultrasounds avoided from 29%–38% (Table 4). Inter-observer agreement for adequate image quality was 0.59 and for compressibility assessments was 0.67 (Table 6). All 6 reviewer groups reached the primary endpoint cut-off of 90% sensitivity.

Discussion

Our analyses produced a wide array of results to consider multiple clinical applications and analytical lenses. All groups demonstrated high sensitivities (90–98%), specificities (74–100%) and NPVs (98–99%). The addition of a second reader consistently improved clinical performance over single-reviewer bootstrapping.

Though clinical performance was high with both groups of reviewers, for a given analysis group the EM POCUS reviewers typically had higher sensitivities, specificities, NPVs, and PPVs, but lower expert-led ultrasound scans avoided. The agreement between the EM POCUS reviewers for adequate image quality is much higher than the radiology reviewers. This possibly reflects their increased comfort and experience interpreting POCUS images. EM POCUS reviewers reviewed the same images as the radiology reviewers under the same conditions. Their improved performance suggests that different reviewers can impact the performance of the system, and diverse groups of reviewers should be assessed as a confounding variable in future studies.

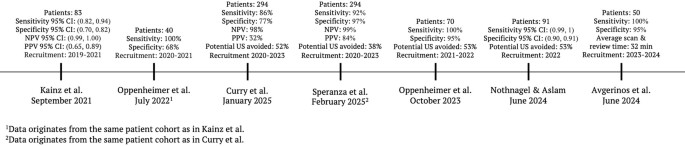

Our study provides another important data point in tracking the performance of AI-guided ultrasound acquisition longitudinally across different populations and geographic areas, highlighting the model’s robustness. Figure 2 displays a timeline of peer-reviewed studies with key performance characteristics from each. None of the patients or scans in these studies were used to train the underlying AI guidance model.

The timeline is ordered by patient recruitment start date to reflect the latest development stages and optimisation of the AI guidance technology chronologically. The reported results show qualified clinician review performance incl. bootstrapping methodology where available. (CI = Confidence Interval, NPV = negative predictive value, PPV = positive predictive value, US = Ultrasound).

Patients have been prospectively recruited across the UK, Germany and Greece since 2020 and the technology has shown consistent results. Kainz et al. assessed net monetary benefit and standalone AI performance6. Oppenheimer et al. (2022) evaluated qualified clinician review on the same patient cohort as Kainz et al. 13. Oppenheimer et al. (2024) and Nothnagel et al. analysed the performance of qualified clinician review across multiple sites and Avgerinos et al. deployed AI-guided ultrasound image acquisition in combination with D-dimer testing to assess improvements in patient management10,14,15.

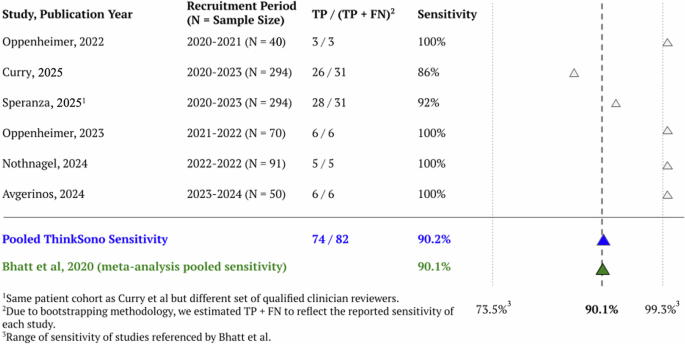

Multiple studies have validated compression ultrasound for lower extremity DVT. Bhatt et al. reviewed 43 studies of various lower extremity DVT diagnostic modalities in over 10,000 patients. Sensitivity and specificity of proximal compression ultrasound were 90.1% and 98.5%, whole-leg compression ultrasound were 94.0% and 97.3%, serial compression ultrasound at various time points were 97.9% and 99.8%, and D-dimer alone were 96.1% and 35.7%, respectively3. Fig. 3 shows the distribution and pooled sensitivity of qualified clinician review in prospective ThinkSono Guidance studies in the context of the results of Bhatt et al.’s meta-analysis, demonstrating the system’s performance falls in the expected range for the validated technique3.

Results are compared to the range of sensitivities and total pooled sensitivity (90.1%) as reported in the Bhatt et al. meta-analysis. FN = False Negative, TP = True Positive. Note, the green triangle shows the pooled sensitivity of ThinkSono Guidance and the blue triangle shows the pooled sensitivity reported by Bhatt et al. reflecting standard of care.

Garcia and colleagues evaluated the accuracy of POCUS 3-point compression ultrasound alongside Wells scores and D-dimers in 109 patients presenting to an ED. They compared the results of compression ultrasounds performed by emergency physicians to Doppler ultrasound scans performed by their radiology expert counterparts. Emergency physician-performed ultrasound had a sensitivity of 93.2%, a specificity of 90.0%, an NPV of 91.8%, a PPV of 91.7%, and an accuracy of 91.7%16. Similar literature has also assessed compression ultrasound for the diagnosis of DVT in inpatient and ambulatory settings, with similarly strong performance17,18.

Zuker-Herman and colleagues prospectively compared 2-point compression ultrasound (2PCUS), 3-point compression ultrasound (3PCUS), and duplex ultrasound for DVT diagnosis in the ED. In 195 patients, 2PCUS had a sensitivity of 82.8%, a specificity of 98.6%, and an NPV of 90.0%, while 3PCUS had a sensitivity of 90.6%, a specificity of 98.5%, and an NPV of 96.4%19.

Pomero et al. performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of emergency physicians performing compression ultrasound for proximal lower extremity DVT. They reviewed 16 studies totalling nearly 2500 patients. DVT prevalence was 23.1% (range 7.4%–47.3%), and mean sensitivity and specificity were 96.1% and 96.8%, respectively. However, in individual studies these figures ranged from 70.4%–100% for sensitivity and 78.6%–100% for specificity4.

Our results are generally consistent with the literature and place the performance of AI-guided ultrasound image acquisition within the range expected from validated compression POCUS protocols. This literature helps underscores the adaptability and accessibility of ultrasound across a variety of clinical settings and operators and highlights operational advantages, like the ability to offer rapid diagnosis without requiring specialised personnel for interpretation.

These studies also discuss hurdles to the implementation of POCUS for DVT and note variability in individual study reports of sensitivity and specificity, as well as differences in operator experience and training. This underscores the potential benefit of a ‘smart’ guidance platform, enabling a variety of operators to obtain consistent, quality images, as well as a streamlined platform to enable rapid diagnostic assessment by operators and/or specialised reviewers.

There is a growing body of literature discussing the potential of AI applications in ultrasound. For cardiovascular diseases, echocardiography has been an area of focus. Deep learning models have been used to process echocardiography images, resulting in highly accurate detection of anatomic structures and landmarks, as well as pathology detection. Some of these models have outperformed echocardiographers in certain circumstances5. AI guidance technology has also allowed non-expert operators to obtain diagnostic-quality images. AI has been applied to the vasculature as well, frequently as an analytical aid in classifying arterial plaques and calculating carotid intima-media thickness. The application of AI guidance to vascular ultrasound, particularly in the venous space, remains a novel and relatively unexplored area5.

The potential benefits of an AI-enabled DVT diagnosis platform and the application of AI to ultrasound extend beyond the quality of care into its cost-effectiveness. The percentage of potential expert-led ultrasound scans avoided in our analysis ranged from 29%–53%. Patients with indeterminate reviews or reviews suggestive of a DVT require further testing and duplex ultrasound. We suggest that patients whose guidance systems scans are negative for DVT are unlikely to have DVT and do not require further duplex ultrasound scans, resulting in an ‘expert-led ultrasound avoided’ percentage. The detailed economic impacts of reducing the number of duplex ultrasounds performed by up to 50% can result in significant cost savings6. Building on the health economic analysis by Kainz et al., examining AI-guided DVT diagnosis within the UK healthcare system, we extend the same evaluative framework to the results presented in Tables 3 and 46. Prior publications reported a maximum net monetary benefit (NMB) – at a hypothetical cost £0 for the AI guidance – of (£71, £139) for three out of five DVT workflow integration strategies, assuming a willingness to pay of £20,000 per QALY at a sensitivity range of (0.82, 0.94) and specificity of (0.70, 0.82) with a positive NMB up to device costs of (£75, £175) per examination6.

Applying this analysis framework to the performance metrics reported in Tables 3 and 4 of this paper yields two key observations: (1) Unlike the findings by Kainz et al., where only three of the five DVT workflow strategies exhibited a positive maximum NMB, the results from our study indicate that all five strategies show positive NMB, up to a cost of (£90, £120) per AI-guided examination. (2) The maximum NMB across all strategies improved when incorporating EM POCUS review, with values increasing to (£113, £208).

In addition to direct cost reduction, codified POCUS workflows have been shown to increase POCUS utilisation, hospital income, and the quality of patient care and outcomes20. In a study by Rong et al. about incorporating a POCUS ED workflow into their institutional electronic health record system in the United States, they found a nearly 30% increase in the number of POCUS examinations performed after implementation. The percentage of POCUS exams with complete and appropriate documentation increased from 14.7% to 94%. Revenue from billable POCUS scans increased from $546.01 to $22,014.47 after implementation20. An AI-enabled platform as discussed here, with its ability to facilitate rapid, accurate diagnosis of DVT, communication, and documentation of these results, has the potential to provide similar benefits to patients, providers, and facilities.

Our analysis is subject to the limitations of the underlying database7. In addition, the retrospective nature of our analysis has the potential to introduce bias. Another limitation of a retrospective analysis is the inability to measure the AI software performance when including communication between the novice ultrasound operator and the clinician reviewing the data. In a prospective study carried out by Avgerinos and colleagues, whereby communication was enabled between the novice operator and radiology reviewers, a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 95% (N = 50) was achieved15. This suggests that the performance of the AI software in retrospective studies with no communication may reflect the lower bound of the performance. Further studies will be designed to include this stratification and expanded analysis on a prospective basis.

Data sharing

Qualified scientific and medical researchers can address requests for de-identified individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article to [email protected]. Proposals for data will be evaluated and approved by ThinkSono, Ltd. at its sole discretion. All approved researchers must sign a data access agreement before accessing the data. Data will be available as soon as possible but no later than within 1 year of the acceptance of the Article for publication and for 3 years after Article publication. ThinkSono, Ltd. will not share data from identified participants or a data dictionary.

Responses