Vector choices, vector surprises

Not all plasmids are fine

Last year, the VectorBuilder team and colleagues published a preprint6 that set off some alarm bells about plasmids. They called for community-wide standards and resources to uphold the quality of gene delivery vectors in research and medicine. In their analysis of 2,521 plasmids that they had received from their academic and industry clients, the company researchers documented design and sequencing errors. These plasmids had been sent to them with customer requests to, for instance, modify the plasmids in a specific way or to package them into recombinant viruses. As the team noted, “in total, we estimate that 45–50% of lab-made plasmids have undetected design and/or sequence errors that could potentially compromise the intended applications.”

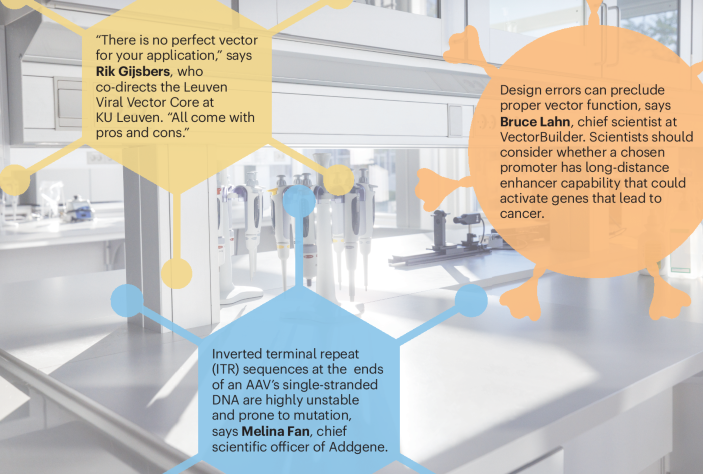

As they worked on this project over months, says Lahn, they wanted to share that the research community was “severely underappreciating the huge problem with gene delivery tools.” They found design errors serious enough to preclude proper function. They saw cases in which the design is proper, but the sequence itself, “the A’s and G’s and T’s and C’s in the vector are not what people think they are.” It dismayed the team to find almost half of the vectors they had been sent had issues. Since they published this preprint, a number of organizations — vector repositories as well as universities — have reached out to them to begin discussing standard operating procedures together, says Lahn. These conversations are in an early stage, he says. But awareness is growing as people explore how to address this.

Around half of the VectorBuilder’s customers work in academia and the other half in industry, says Lahn. They might work on basic cell biology questions such as in cancer or neuroscience research; they might also be exploring plant and food projects, as well as ‘green energy’ projects involving carbon capture. Quality matters across basic and applied research and is certainly critical in gene therapy projects, a rapidly growing area, the VectorBuilder team says.

In her view, says Fan, the manuscript makes a strong case for the existence of a repository like Addgene, where a quality control team tests all the plasmids that come in from labs before distributing them to others on demand. The study hasn’t decreased interest in scientific sharing of plasmids, she says. In fact, given the easier access to DNA synthesis, “scientists are creating and using plasmids more than ever.” Strong support for open science, which includes reagent sharing, has added to the interest in depositing plasmids with them. Looking forward, she says, “We are interested to see how this area continues to evolve with AI-generated sequences, which will further drive large-scale plasmid synthesis and testing.”

Sometimes, says Lahn, people skip quality control of vectors because they over-trust the lab that sends them a vector. He sees far too often that people plan a multi-year project for PhD research or a postdoctoral fellowship and blindly take something from a colleague’s freezer and plunk it into their experiment. “It’s remarkable,” he says, but not in a good way. After all, a finding can be rendered useless if it’s “an artifact of a vector that actually isn’t doing what it’s supposed to do or has the wrong sequence.” Skipping quality control (QC) certainly does not pass muster in labs working on the burgeoning area of gene therapy, but he thinks that basic research labs, too, must tend to QC.

Credit: Photo by mckeephotography.com for Addgene; T. Phillips, Springer Nature

Sequence it

In their analysis of sequencing errors in plasmids, VectorBuilder compared Sanger sequencing results with data from commonly used sequencing methods for validating plasmids such as nanopore sequencing. They note that, “In all cases where discrepant results were produced, Sanger always gave the correct sequences.” That is why, for their analysis, they relied exclusively on Sanger to validate plasmid sequence.

With high-throughput sequencing, “the error rate is a little too high for comfort,” says Lahn. This may change over the next few years, but for now, and especially for clinical applications, methods are needed that assure accurate sequence. Labs might outsource sequencing vectors to a company, but, he says, errors can creep in there, too. Most long-read methods are more likely to be error prone. “Check the sequence,” says Lahn to all researchers. And for demanding applications, “Make sure it’s Sanger.”

Sanger sequencing instruments and expertise are not found in every lab, says VectorBuilder applications scientist Charles Bai, who was interviewed jointly with Lahn. But a core facility will have access to Sanger sequencing. On university campuses he frequently sees boxes into which scientists can drop vectors and receive the sequence the next day. “I think the barrier of doing proper Sanger sequencing and, in general, QC for their cloning product is really, really insignificant nowadays,” says Bai. Sanger sequencing is, in his view, the most reliable way to QC a plasmid.

Says Fan, the prevalence of sequence errors in lab-made plasmids is precisely why sharing via a central resource that conducts QC matters. Addgene’s sequencing step identifies sequence discrepancies from the predicted sequence, and, she says, “We are able to work with depositing scientists to get new versions of the plasmids if necessary or simply publish the correct sequence on the website with notes for end users.”

Addgene conducts full sequencing of the plasmids in its repository. Only recently has the technology for full plasmid sequencing become more affordable and available, she says. With services such as Plasmidsaurus, for instance, which offers full plasmid sequencing for around $15 per sample, it’s become easier for scientists to conduct their own quality control before their experiment begins, she says. The sequences on Addgene’s site are a combination of results from high-throughput sequencing, long-read sequencing and Sanger sequencing. “We have found that different technologies have different strengths based on the sequence,” says Fan.

It’s by design

Design errors can be blatantly apparent or subtle and hard to detect, even for experts, says Lahn. For instance, an inserted transgene can unintentionally activate a neighboring gene. A promoter may act as an enhancer that is likely to activate genes at a distance. For instance, when using a lentiviral vector, which generally tends to integrate into the genome, oncogenes can be activated. Lahn wonders if cancer cases in some gene therapy trials may be due to such aspects of vector design. He recommends scientists ask themselves before an experiment if the chosen promoter has this type of long-distance enhancer capability.

Says Fan, plasmid design errors can occur because young scientists are still learning how to design plasmids or “because biology doesn’t always behave the way we expect it to.” That is why she thinks Addgene’s resource of published and vetted plasmids is so important. Not all plasmids that researchers make in the lab work as expected, but the ones that end up in the publications and are deposited with Addgene are the small subset that did work. Scientists who use them can read the paper and compare to their own results. That is “fantastic for reproducibility,” she says. The more the community learns about plasmid design and shares that information with one another, “the better our community toolbox will be.“

The VectorBuilder analysis found that AAV transfer plasmids used to package recombinant AAV virus had highly mutable inverted terminal repeat (ITR) sequences. Around 40% of the plasmids had mutations relative to the wild-type ITR sequence. ITR instability is associated with high G+C content of the immediate flanking sequence.

Fan says she and her team, too, have observed that the majority of AAV plasmids in public use have a mutation in one of the ITRs. In internal studies at Addgene, the team has found that minor mutations in a single ITR, when present with a wild-type ITR, still allow AAV production and use, but “we are able to get better production yields with two canonical ITRs.” This has led Addgene to build a backbone with two canonical ITRs for public use. Researchers should keep in mind, she says, that “even if a plasmid starts with two canonical ITRs, the ITRs are unstable and prone to mutation.”

Another task for researchers is to check vector stability, sags Lahn. As the team notes, to achieve greater stability one should clone sequences into low-copy plasmids and use tailored Escherichia coli hosts along with special culture conditions such as low temperature, low salt and adjusted antibiotic concentration. “We agree,” says Fan. Addgene uses and recommends that scientists use recombination-deficient strains for certain plasmids, including viral plasmids.

Credit: VectorBuilder

Dilemmas: immunogenicity and cancer

Viral vectors that deliver reagents or a nucleic acid payload are used in basic research as well as clinical applications. Some results in gene therapy are urgent calls to basic research labs to tease out mechanisms that might underpin these surprises.

One issue is vector immunogenicity. “AAVs are highly immunogenic,” says Johnny Mahlangu from the Department of Molecular Medicine and Haematology at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. His request to basic researchers: “The immunology of AAV vectors requires close studying in order to design non-immunogenic vectors,” he says. Epidemiologic studies, he says, indicate up to 90% of people in certain regions of the world have anti-AAV antibodies, which reduces the number of people who could potentially benefit from AAV-based gene therapy.

Other types of clinical surprise direct important questions back to basic researchers, too, notably when cancer develops in some people who receive AAV-based gene-therapy. In The New England Journal of Medicine Mahlangu authored an editorial7 about a recent study in which lentiviral gene therapy was used to treat hemophilia A. People received an autologous transplant of CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells that had been transduced with a lentiviral vector. Five people in this trial showed stable expression of factor VIII, a protein that is low or lacking in people with hemophilia A. No deaths or complications were noted.

This does not settle lenti-AAV decision-making, and both he and the authors of this study note that it remains an open question whether a lentivirus-based approach can overcome current challenges associated with AAV-based gene-therapy. For instance, existing treatments with AAV-based approaches that deliver a functional B-domain-deleted F8 transgene are not always successful; anti-AAV antibodies present challenges, as does the uncertainty over how durable factor VIII expression can be.

Unlike AAVs, which typically have an episomal location, says Mahlangu, lentiviral vectors tend to integrate into the genome. Might this integration have led to cancer in some gene therapy cases? Cancer might have also been triggered by medications used for pre-gene-therapy conditioning. In the aforementioned lentivirus-based study, the medications used for conditioning were different from the ones used in a bluebird bio gene therapy study with children in which cancer was observed. For now, it’s not definitive whether lentivirus-based approaches avoid the complication of cancer development.

In that pediatric gene therapy study on slowing progression of the neurodegenerative disease cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy, 7 of the 67 children in the study developed blood cancers after treatment. The trial used a lentiviral approach, in particular Lenti-D, an HIV-1 derived vector that has been engineered to not replicate. In the 6 children with available data, the researchers found clonal vector insertions within oncogenes. The study involved a US Food and Drug Administration-approved gene therapy from bluebird bio that uses transduced CD34+ cells.

Speaking generally about lenti-AAV decision-making, Ben Kleinstiver, a researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital says, “Lenti, by its nature, integrates into the genome,” whereas AAVs tend to largely stay episomal, but they can, on occasion, become part of the genome in the host cell. This tendency of lentis is why he and his team avoid lentivirus-based approaches in their gene-editing experiments using CRISPR and base editing. The team developed a method called ‘click editing’8 that harnesses DNA-dependent polymerases and short DNA templates, for which non-viral delivery modes are needed.

The field, says Kleinstiver, has gained a deeper appreciation of the way AAV can get captured into the genome, especially when a Cas9 nuclease is used along with AAV delivery. In applications in which scientists are using AAV as a homology-directed repair template, they often see the entire AAV genome get captured into the break by a poorly characterized end-capture mechanism, he says. The homology arms in the homology-directed repair donor within the AAV somehow do not come into play.

Such moments happen in experiments when one tries to deliver a nuclease via AAV to knock out a gene. Instead of just getting small insertion or deletion mutations from the nuclease, he says, “the DNA break generated by the nuclease can also ‘accept’ an integration event from the AAV genome.”

Overall, the cancer risk appears to be low in any given cell, he says, “but when transducing millions or even high billions of cells, then even rare events can initiate cancer.” With lentiviral vectors, some cases of genome integration may be unproblematic because they do not disrupt important genes or regulatory elements, “but there have been cases where the strong exogenous promoter encoded in the viral cassette can inadvertently drive expression of an oncogene.”

Whenever one injects large amounts of genetic material, says Gijsbers, whether this involves plasmids or AAV, genome integration can happen. When using cancer cell lines, he and his team find it difficult to use recombinant AAV (rAAV) as a donor and have it integrate at a specific, desired position. rAAV is used in approved gene therapies and approaches still being evaluated.

One mechanism, says Gijsbers, that underpins AAV integration is mediated by Rep, a protein produced by the rep gene. A locus on the human chromosome 19 has homology with the AAV rep sequence such that the virus can integrate and reside there as a latent virus. In rAAV, the rep and cap genes are removed and the only remaining viral genome sequence are the inverted terminal repeat sequences, which are needed to package the vector genome. These rAAV vectors “can no longer integrate,” he says, at least not by this Rep-mediated route.

When one uses large quantities of AAVs and injects them in vivo, genomic integration indeed becomes more likely, says Lahn. Scientists might not see cancer develop in work with mice, due to the animals’ limited life span or the duration of experiments. But researchers should remember that down the line, their findings might lead to gene therapies that could become lifelong treatments during which much virus will stay in a person’s body. If the vector promoters carry a long-distance enhancer, it’s a possibility that this may activate nearby endogenous oncogenes.

What is sometimes forgotten about rAAV, says Anna Maurer, who has just opened her lab at the University of Michigan, is its simplicity as a protein shell that contains one single-stranded piece of DNA. While other viruses and vectors carry enzymes that directly express the foreign gene or that set up a cellular environment to do so, an rAAV relies almost entirely on host cellular factors to get things done. “And it’s a two-way street: vector–host interactions determine both on and off,” she says.

Over time, the body does want to silence a foreign gene, she says, especially when it’s being overexpressed, as is the case with cytomegalovirus-derived promoters. Given that rAAV vectors are difficult to re-dose, “We need to understand why and how silencing occurs, especially the host factors’ roles,” she says. Knowing this would help scientists explore how to prevent such silencing or how to reactivate expression when therapies fail over time. “This is one of my new lab’s research directions.”

Credit: Solskin / Getty Images; Thomas Phillips, Springer Nature

As for immunogenicity, anything that is injected can trigger an immune response, says Gijsbers. The degree to which it does so depends on the dose and the organs or tissues being targeted. Says neuroscientist Robrecht Raedt of the University of Ghent, “We have so far had great experience with AAVs to induce transgene expression in the brain of models for epilepsy.” The team models epilepsy in rats and mice.

Raedt and his team use chemogenetic methods to explore the underpinnings of epilepsy and how to use selective neuromodulation. Down the line, this could help find ways to avoid the often severe side effects of antiepileptic drugs. Raedt and his team use selective expression of inhibitory Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADDs) to set up cell-type-specific experiments9.

With AAV2/7 and the CamKIIa promotor, they achieved the expression levels they sought in hippocampal excitatory neurons. Off-target expression levels were quite low, he says. And because the CamKIIa promotor is small, they were able to package all they needed into the AAV. With an AAV-based DREADD for chemogenetic modulation, they saw some toxicity in rodents, which became apparent only after three weeks. Their sense is that the toxicity is linked to DREADD expression rather than the AAV, says Raedt.

Lower levels of AAV led to no toxicity and gave stable expression that lasted up to one year. The scientists did not check integration into the host DNA. But this propensity of lentis to integrate is why they explicitly chose AAVs, “because they presumably don’t integrate in host DNA.” They also targeted the brain’s locus coeruleus (LC) with a specific promotor. In a result that he calls “very strange,” when they used the AAV-based construct they saw much off-target expression in nuclei surrounding the LC and very little expression in the LC itself. However, when they used a vector designed with canine adenovirus type 2, “We got highly specific expression in LC without significant off-target expression.” They did not check for genome integration there.

Fan sees a number of labs designing new versions of AAV capsids — the outer protein shell that encapsulates the genetic payloads. New AAV capsid design promises to decrease immunogenic response to AAV in people. With AAVs in laboratory animals, immunogenicity “is not a major problem,” she says, because most animals lack anti-AAV antibodies.

VectorBuilder offers capsid evolution services to engineer vectors with lower immunogenicity. Says Bai, capsid engineering can also render gene delivery more efficient. Methods are in development to not only enhance delivery but, he says, to “de-target the AAV” to a tissue that otherwise becomes too heavily trafficked, such as the liver. It’s challenging but promising work, he says.

Says Fan, with AAV capsid engineering, one can target delivery of a gene of interest such as to only the neurons of the eye and minimize off-targets elsewhere in the body. Scientists deposit their new capsids with Addgene and labs will request them for their tissue- or cell-targeting experiments, she says. Addgene distributes them and can package genetic material in them upon request.

“Time constraints seem to keep people from tending to quality control,” says Bruce Lahn.

Not a lot of AAV luck

Cosmo was a bull generated in the lab of Alison Van Eenennaam at the University of California, Davis. He was the first bovine with a large knock-in gene, she says. His genome had been edited with CRISPR–Cas9. Van Eenennaam uses gene editing of farm animals to develop DNA-based approaches in agriculture, and she and her team are exploring how one can use gene editing to, for instance, model human disease in sheep.

With Cosmo, they had inserted the SRY gene into embryos during in vitro fertilization — it’s the gene that shapes male sexual development in cattle. They also added a reporter gene, a GFP construct, to make it easier to screen embryos and check for the gene insertion they sought.

When they sequenced Cosmo’s genome after his birth, they saw he had the SRY-GFP construct and a copy of the plasmid backbone used to ferry in the genetic material, too. These days, she says, “Typically we do not use a vector at all now when we are editing.” They use a CRISPR-based approach with a ribonucleoprotein complex and target a sequence of interest with a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN). When devising a ‘simple knockout’, they use no template, she says. “I have dabbled with AAV to see if we could get better rates of knock-ins, but we did not have much luck,” she says. That’s why she and her lab moved to other approaches.

The plasmid backbone integrated in Cosmo’s case through an end-capture mechanism, says Van Eenennaam. What was more problematic, in her view, is that multiple copies of the transgene integrated, which commonly leads to gene silencing. Cosmo’s daughter, Cosmonaut, is XX/SRY+ and seems to be a fertile female. Van Eenennaam has only taken a single live animal through to sexual maturity: gene-edited cattle are expensive in upkeep, as well as to dispose of.

In a collaboration with others at University of California San Francisco, the researchers achieved particularly high rates of success with an ssODN template in sheep. They produced heterozygous sheep by gene editing the embryo’s genomes with CRISPR–Cas9 to introduce the gene that produces bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 (BMPR2), which is important in the rare vascular disorder pulmonary arterial hypertension. They took the gene-edited embryos to term as they are working to establish a large mammal animal model for this form of heritable hypertension. They plan to assess aspects such as variable genetic penetrance and to compare male and female animals.

As Lahn says, some vector quality issues are more blatant than others, and some take an experienced eye to detect. Overall, manifold areas of study are still emerging related to vectors, the workhorses in so many life science labs, such as the immunogenicity of vectors and the way some vectors can integrate into the genome in unexpected ways.

Plenty of the advised QC steps are known, says Lahn, and for the most part they are not all that cumbersome to follow. Time constraints are one main issue that he and his team see as keeping researchers from QC steps. Researchers at a young biotechnology company have investors “breathing down their necks” to keep a development pipeline moving. “Maybe they’ll just go with a suboptimal solution.” Says Bai, “the pressure for a graduate student, or postdoc, or even for a PI to get results out is really incredible.”

They have customers, say Lahn and Bai, who can pursue careful, long-term strategies, but others lack that luxury. It’s just fairly certain, says Lahn, that a suboptimal approach “is something that’s going to come back and bite you.”

Responses