Volcanic fertilization of Late Triassic lacustrine algal blooms

Introduction

Although large-scale volcanism is inferred to have triggered numerous climatic-environmental perturbations and biotic crises through Earth’s history1,2,3, the general effect of volcanic ash deposition is to increase the productivity of soils and lacustrine and marine waters4,5,6. This fertilization effect depends on the release of large amounts of nutrient elements (e.g., phosphorus), often from regional volcanic arcs, which can result simultaneously in enhanced primary productivity and widespread mortality in lacustrine and marine ecosystems5,7. Although the local environmental effects of arc volcanism on the Earth-surface system have been investigated, most studies of its climatic impacts have been undertaken from the perspective of mathematical models8,9, with only limited empirical (e.g., sedimentary geochemical) study of volcanic influences on aqueous biotic communities and organic matter fluxes10. In particular, the potential role of intense regional arc volcanism in climate change and as a bioevolutionary driver has received little attention to date.

The Chang 7 Member of the Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin of the North China Craton consists mainly of lacustrine black shale intercalated by volcanic ash layers of varying thickness (Fig. 1), including both airborne and water-borne deposits (Supplementary Notes 1, 2). Given its organic-rich character, this black shale succession is a major target for shale oil and gas exploration. The Chang 7 Member accumulated at rates of ~3 to 8 cm/kyr (mean ~5 cm/kyr) (Supplementary Note 3)11,12, thus preserving an archive of (sub-)millennial-scale variation in volcanic inputs to a paleo-lake system and their effects on water-column productivity.

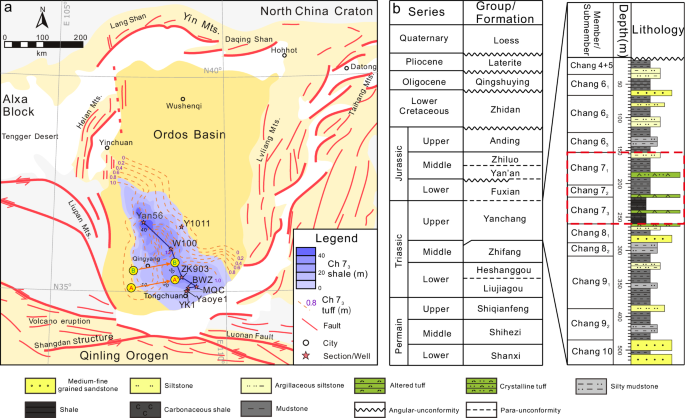

a Simplified tectonic map of the Ordos Basin, north-central China, shows the wells and sections studied in this paper, modified after refs. 15,23. In this study, palynological and geochemical analyses were carried out on wells/sections BWZ, MQC, and Yan56 from southeast to northwest (note the solid black line-of-section connecting the study wells). b Integrated stratigraphic column of the Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin23.

In this study, we sampled volcanic ash and black shale layers of the Chang 7 Member with the goal of exploring changes in environmental conditions and the lacustrine primary producer community before, during, and after individual volcanic eruptions. Scanning electron microscopy was used to analyze changes in the sedimentary lamination of ash layers at a microscale. Palynological and bulk nitrogen (δ15Nbulk), organic carbon isotope (δ13Corg) data, and C/N ratio were used to track changes in the composition of the primary producer community. Corg😛 ratio and enrichment factor of V (VEF) were used as proxies for redox conditions13, and P/Al ratios indicate the input of nutrient elements. Rb/Sr and K/Al ratios are indicators of chemical weathering intensity, and the Zr/Al ratio is indicative of physical weathering intensity, hydrodynamic sorting, or inputs of volcanic ash (see Supplemental Information for details).

Geological setting

The Chang 7 Member was deposited during a phase of subsidence of the Ordos Basin when the lake deepened to over 60 m at its center and expanded to an area of ~65 × 103 km2 (Fig. 1a)14. This unit consists of black oil shale, silty shale, and tuffaceous sandstone enclosing thin volcanic ash layers (Fig. 1b). The tuffs are cm-thick layers of intermediate to felsic character that are enriched in volcanic glass and pumice, having a cumulative thickness of up to 1.2 m15,16. Based on the distribution of ash across the basin, the volcanic center was likely located in the Qinling Orogenic Belt on the southwestern margin of the North China Craton17,18.

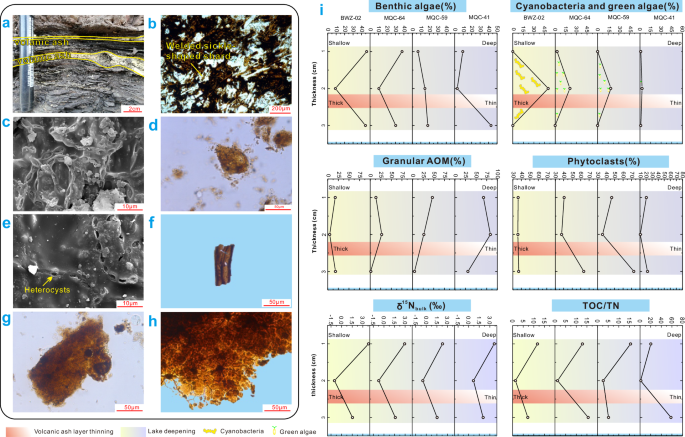

Two types of volcanic ash layer can be distinguished, i.e., airborne and water-borne layers (Figs. 2, 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The former represents direct input of volcanic ejecta into the lake during an eruption and consists of pyroclastic sediments that lack a terrigenously sourced fraction, whereas the latter represents volcanic ash washed into the lake following an eruption, along with admixed detrital quartz and feldspar grains, clay minerals, and plant debris19. Petrographic observation reveals abrupt contact between the ash layers and black shale (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). Thin-section examination reveals that the pyroclasts are composed primarily of glass shards, crystal shards, and a small amount of altered clay (Supplementary Fig. 2c, d). The shales of the Chang 7 Member also contain abundant aquatic algae, and terrigenous coalified plant debris, pollen, and spores20, and the kerogen fraction ranges from Type I to Type III organic matter14,16, suggesting a complex lacustrine ecosystem. In particular, abundant Nostocales Anabaena spp. (Fig. 2c, e) and halophilic green algae (Fig. 2d) are present, implying episodic phytoplankton blooms.

a The interbedded layers of light yellow airborne volcanic ash and black shale (BWZ-09). b “V” shaped glass fragments in airborne volcanic ash (BWZ-23). c Cyanobacteria (Nostocales Anabaena spp.) in the black shale above airborne volcanic ash (BWZ-02). d Planktonic green algae (Dunaliella salina) in the black shale above airborne volcanic ash (MQC-41). e Heterocysts of cyanobacteria (Nostocales Anabaena spp.) (indicated by yellow arrows) in the black shale above airborne volcanic ash (BWZ-02). f Vascular plant fragments (indicated by the yellow arrow) in the black shales above airborne volcanic ash (BWZ-11-4). g Benthic algae in the black shale beneath ash, with circular and unilocular sporangia (MQC-59). h Benthic algae thalli in black shale beneath the airborne volcanic ash (BWZ-03). i Palynofacies, δ15Nbulk and TOC/TN of airborne volcanic ash from proximal to distal areas relative to the location of the volcanic center. The four volcanic ash layers numbered BWZ-02, MQC-64, MQC-59, and MQC-41 are 2.5, 1.8, 1.5, and 1.0 cm in thickness, respectively. BWZ-02 was sampled in BWZ, and others were sampled in MQC.

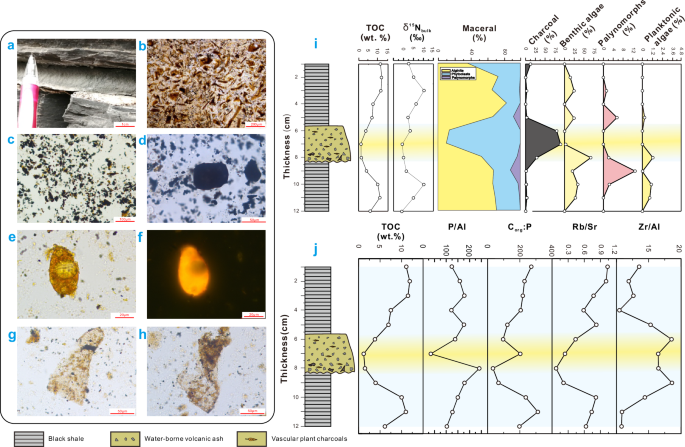

a Tuffaceous sandstone with an upward-fining sequence (MQC-54). b Volcanic glasses cemented by calcite (MQC-53). c, d Charcoal within the tuffaceous sandstone (MQC-54, 7 cm). e Halophilic green algae (MQC-54, 8 cm) at the bottom of tuffaceous sandstone. f Fluorescent image of a panel (e). g, h Benthic brown algae thallus in black shale at the bottom of water-borne volcanic ash (MQC-54, 9 cm). i Biological transformation under the action of water-borne volcanic ash (MQC-54). j Vertical distribution of TOC and elemental ratios in water-borne volcanic ash (yellow shading) and host shale (MQC-54).

An absolute astrochronological framework was developed for the Chang 7 Member, yielding an age range of 235.3 Ma to 233 Ma for the study interval21 with an approximate temporal resolution of 102–103 yr per sample (Supplementary Table 1). Tuning to the 100-kyr short-eccentricity signal yielded average sedimentation rates of 5.6, 5.5, and 5.0 cm/kyr in the Yaoye1, W100, and Yan56 drillcores, respectively (Supplementary Note 3). Palynological analysis of this unit identified three assemblages (from bottom to top): (1) the Lundbladispora communis–Protopinus latebrosa assemblage, (2) the Baculatisporites elegans–Pinuspollenites divulgatus assemblage, and (3) the Apiculatisporis globosus–Taeniaesporites divisus assemblage (Supplementary Fig. 1), supporting an early Carnian (Late Triassic) age assignment for the Chang 7 Member. Taxonomic identifications of green algae, brown algae, and cyanobacteria were based on petrographic study of multiple fossil occurrences. See the Supplemental Information for details of astrochronology, age assignments, and fossil identifications.

Results

Single-layer airborne volcanic ash

The four airborne volcanic ash layers appear as thin yellowish layers in outcrop, each ranging from 0.3 to 3.0 cm in thickness (Fig. 2). A small amount of volcanic felsic crystal pyroclasts can be observed, with normal grain sequence and no obvious erosional base between the volcanic ash layers and subjacent shale (Fig. 2). Centimeter-thick samples were collected from the shales both above and below four sets of volcanic ash layers. A total of 12 samples were analyzed for palynological content to assess the impact of volcanic eruptions on lacustrine algae community composition (Fig. 2).

Recovered palynomorphs include benthic brown algae, phytoclasts, granular amorphous organic matter (AOM), pollen, planktonic cyanobacteria, and green algae (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Note 4). The black shales beneath volcanic ash layers (BVAL) contain abundant benthic brown algae (30.3–42.9%)[notes: all ranges in this study are given as 16–84th percentiles to avoid influence by outliers], phytoclasts (37.3–63.6%), granular AOM (4.6–18.1%), and a small amount of spores (3.1–4.6%), whereas those above volcanic ash layers (AVAL) contain abundant cyanobacteria and a small number of green algae (3.0–18.5%), benthic brown algae (9.1–10.4%) and phytoclasts (35.8–36.4%) (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1). Thus, it appears that cyanobacteria and green algae bloomed after deposition of airborne volcanic ash. The thicker the ash layer, the greater the percentage of the cyanobacteria and green algae in the AVAL (Fig. 2). The δ15Nbulk and total organic carbon/total nitrogen (TOC/TN) values in the black shales close to a volcanic ash layer are lower than those in background shales (Fig. 2).

Elemental scanning analysis shows that the abundance of P in the volcanic ash is higher than in the BVAL and AVAL (Supplementary Figs. 5, 6). This observation indicates that the ashfall events were P-rich. The existence of high levels of P in lake waters following each eruption likely increased lacustrine primary productivity and organic carbon sinking fluxes (Supplementary Fig. 5). Similar to P, the element N also increases within each volcanic ash layer (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Single-layer water-borne volcanic ash

A single water-borne volcanic ash (~2 cm) appears as a thin gray layer in the outcrop (Fig. 3a). Clasts in this layer include volcanic vitreous debris, scattered clay minerals, and charcoal fragments (Fig. 3b, c, d). Palynological investigation was undertaken on twelve samples from below, within, and above this layer in the Maquancun (MQC) section of the Tongchuan area of the Ordos Basin. The amount of black charcoal (~80%) is high in the water-borne ash layer, and the presence of coalified spores (Fig. 3c, d) suggests that the detrital material originated from a region with wildfires. Notably absent are green and benthic brown algae, although a small amount of halophilic green algae (0-0.93%) is present in the lower part of the ash layer (Fig. 3e, f). In contrast, both the BVAL and AVAL contain abundant planktonic green algae and benthic brown algae (6.4–35.0%) (Fig. 3g, h). Spores and pollen (0–1.2%) are more abundant in the AVAL than the BVAL (Fig. 3i). The δ15Nbulk in the water-borne volcanic ash layer (+0.01‰) has a slight decrease compared to black shale (+1.4 to +10.2‰) (Fig. 3j).

Elemental analysis of the black shale and intercalated water-borne volcanic ash layers shows (Supplementary Note 5): P/Al ratios indicating nutrients increase rapidly at the base of the water-borne volcanic ash layer, but quickly decrease to normal levels upward in the AVAL (Fig. 3j). The Rb/Sr ratios decrease in the water-borne volcanic ash layer and in the shale beneath in the BVAL, whereas the Zr/Al ratio increases in the water-borne volcanic ash and the shale beneath (Fig. 3j). Corg😛 ratio gradually increases in the AVAL (Fig. 3j).

Full section records

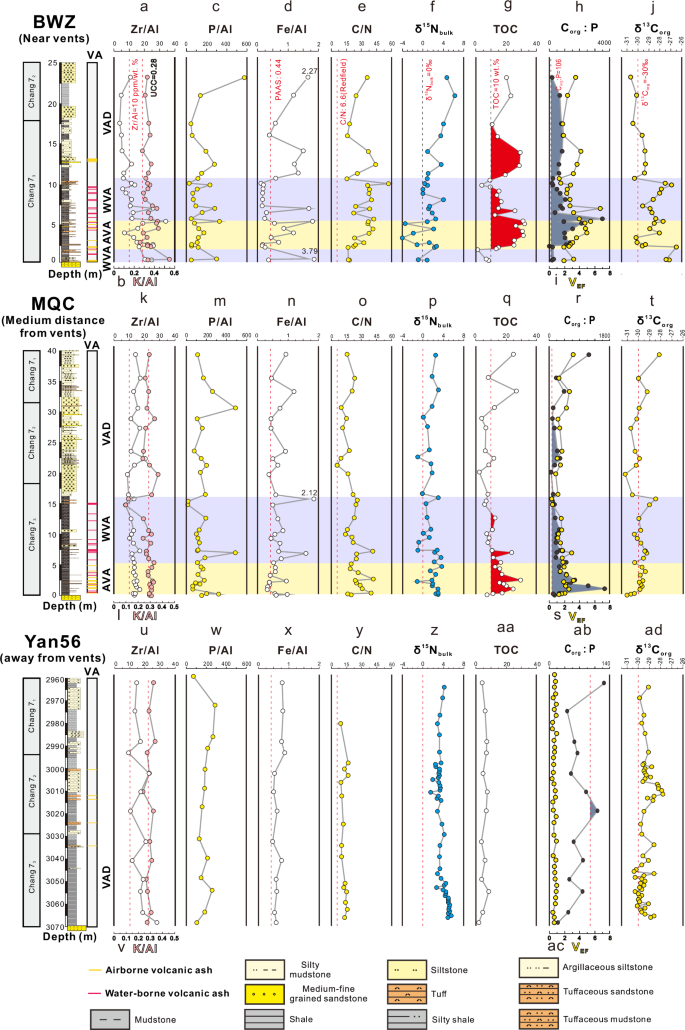

The three sections were divided into airborne ash-rich, water-borne ash-rich, and non-ash shale intervals (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 2). In the Bawangzhuang (BWZ) section (Fig. 4), which contains abundant volcanic ash layers in the Chang 73 Submember, the shale exhibits high Zr/Al ratios within the airborne ash-rich interval (at 2–6 m), surpassing that of the water-borne ash-rich interval (at 0–2 m and 6–11 m). Compared to the water-borne ash-rich and non-ash shale intervals, the airborne ash-rich interval yields lower δ15Nbulk (–3.42 to +2.55‰, median +0.88‰) and higher TOC (14.9–31.4 wt%, median 26.4 wt%), Corg😛 (1014–2131, median 1179) and VEF values (2.84–4.99, median 3.99).

a, k, u Ratios of zirconium to aluminum (Zr/Al, ppm/%); b, l, v Ratios of potassium to aluminum (K/Al, %/%); c, m, w Ratios of phosphorus to aluminum (P/Al, ppm/%); d, n, x Ratios of total iron to aluminum (Fe/Al, %/%); e, o, y Ratios of total organic carbon to total nitrogen (C/N, mol/mol); f, p, z Bulk nitrogen isotope (δ15Nbulk, ‰); g, q, aa Total organic carbon content (TOC, wt%); h, r, ab Ratios of total organic carbon to phosphorus (Corg:P, mol/mol); i, s, ac The enrichment factor of vanadium (VEF); j, t, ad Organic carbon isotope (δ13Corg, ‰); VA Volcanic ash, WVA water-borne volcanic ash-rich interval, AVA airborne volcanic ash-rich shale interval, VAD volcanic ash-devoid shale interval. Zr/Al (a, k, u), K/Al (t), TOC (g, q, aa), and Corg😛 (a, b) data from refs. 23,67. C/N (y), δ15Nbulk (z), and δ13Corg (ad) data from ref. 68, VEF (ac) data from ref. 55. The lithologic columns are from refs. 67 and 23.

In the MQC section (Fig. 4), which contains abundant volcanic ash layers in the Chang 73 Submember, the shale exhibits high Zr/Al ratios within the airborne ash-rich interval (at 0–5 m), surpassing that of the water-borne ash-rich interval (at 5–15 m). The airborne ash-rich interval has low δ15Nbulk (+1.69 to +2.91‰, median +2.44‰) and high TOC (12.7–20.1 wt%, median 17.2 wt%), Corg😛 (290–735, median 494) and VEF values (1.66–2.28, median 2.08).

The Yan56 core (Fig. 4), which contains fewer volcanic ash layers than the BWZ and MQC sections due to greater distance from the volcanic source area, has relatively higher δ15Nbulk (+3.1 to +4.9‰, median +3.8‰) and lower TOC (3.7-7.2 wt%, median 6.1 wt%), Corg😛 (65–98, median 76) and VEF values (0.57–0.96, median 0.72). Thus, regionally across the Ordos Basin (i.e., from Yan56 in the NE to BWZ in the SW), the volcanic ash-rich intervals show a decreasing trend of δ15Nbulk and increasing trends of P/Al, TOC, C/N, Corg:P, VEF, δ13Corg, and K/Al (Fig. 4).

Discussion

The geographic distribution of ash layers in the study cores provides a clear indication of the source of volcanic ash in the Ordos Basin. Petrographic observations show that BWZ and MQC have the largest number of volcanic ash layers (39 and 28, respectively), while few ash layers were detected in Well Yan56 (further to the NE), likely due to its greater distance from the volcanic center located along the southwestern margin of the North China Craton (Figs. 1, 4). The content of Zr can be used to indicate the contribution of bentonite in black shales22. The Zr/Al ratio, an indicator of the relative content of cryptotephra in black shales (Supplementary Note 5), shows a positive correlation with TOC in BWZ and MQC, and a negative correlation with Yan5623, indicating a gradual decrease in cryptotephra input toward the northeastern region of the Ordos Basin, a pattern consistent with the volcanic ash distribution (Fig. 1a). Given the substantial impact of airborne volcanic ash on algae communities and organic carbon sinking fluxes, the main focus of the paper is to discuss the effects of airborne volcanic ash on lacustrine productivity at a range of timescales from decadal to mega-annual.

δ15Nbulk can provide information regarding cyanobacterial abundance and rates of N fixation at a given site. In moving from NE (Yan56) to SW (BWZ) across the Ordos Basin, δ15Nbulk values gradually decrease (Fig. 4), indicative of greater cyanobacterial N fixation (δ15N ~ 0‰), presumably linked to increasing N deficiency as a consequence of an excess of volcanically supplied P. Moreover, δ15Nbulk near to individual airborne and water-borne volcanic ash layers falls sharply (Figs. 2, 3), and abundant cyanobacteria were found in the ash-rich interval through palynological analysis (Fig. 2c, e). Nitrogen fixation by cyanobacteria (i.e., diazotrophy) is the primary source of new bioavailable nitrogen to the oceans24,25,26,27. The δ15Nbulk values of organic matter generated through diazotrophy correlate with atmospheric nitrogen isotopes, exhibiting minimal fractionation, approximately –3‰ to 0‰28,29,30. Negative nitrogen isotope excursions can also be interpreted as being derived from terrestrial plants31,32. However, we observed that during periods of negative nitrogen isotope excursions (Fig. 4f), there is also a corresponding negative excursion in organic carbon isotopes (~-30‰) (Fig. 4j), indicating a source from bacteria and algae, which contradicts the terrestrial plant origin33. Therefore, the negative nitrogen isotope excursion is still related to cyanobacteria. In modern oceans, diazotrophy and nitrogen reduction in the water column reach a relative equilibrium, with δ15NNO₃⁻ values in deep waters approximately +5‰34. In older sediment, δ15Nbulk has been demonstrated to faithfully record processes of low thermal maturity in the water column. Further confirmation of the authenticity of overall δ15Nbulk in ancient organic-rich sediments has been provided through δ15N analysis of chlorophyll-derived porphyrins35.

Differential microbial communities, e.g., cyanobacteria, can also be distinguished based on C/N ratios (Supplementary Note 5). Laboratory data analysis indicates that during early and maximum primary producer blooms, the C/N ratio exceeds the Redfield ratio because total N uptake exceeds that of regeneration36. Conversely, during post-bloom periods dominated by consumer interactions, the degradation of low molecular weight organic carbon leads to a reduction in the Redfield ratio37. In this study, the highest C/N ratio is observed in BWZ, followed by MQC, and the lowest in Yan56 (Fig. 4), likely correlated with the cyanobacterial bloom.

The cause of cyanobacterial blooms can be attributed to inputs of P being greater than that of N during volcanic eruptions (Fig. 5), leading to nitrogen deficiency in the water column. Alternatively, it also may result from the increase in the redox interface due to oxygen depletion, reducing the NO₃⁻ reservoir38, as evidenced by the high VEF and Corg: P values in the BWZ section (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 5), indicating an anoxic environment. Nitrate is the dominant bioavailable nitrogen species in most ecosystems37. The presence of O₂ in the surface water layer controls the distribution of NO₃⁻ ions, with abundant NO₃⁻ distributed above the oxic or suboxic interface and abundant NH₄+ below it39, as NH₄+ is stable under anoxic conditions24,40. Changes in δ15N are mainly influenced by dissolved inorganic nitrogen (NO₃⁻, NO₃⁻, and NH₄+). When NH₄+ enters above the oxic or suboxic interface, it undergoes denitrification to produce NO₃⁻ and NO₃⁻. At this point, a substantial fractionation of N occurs, with εdenitrification ranging from +20 to +30‰34, resulting in a residual NO₃⁻ pool substantially enriched in 15N. However, as the redox interface becomes shallower, the concentration of NO₃⁻ in the water column decreases sharply, leading to intensified biological nitrogen fixation41.

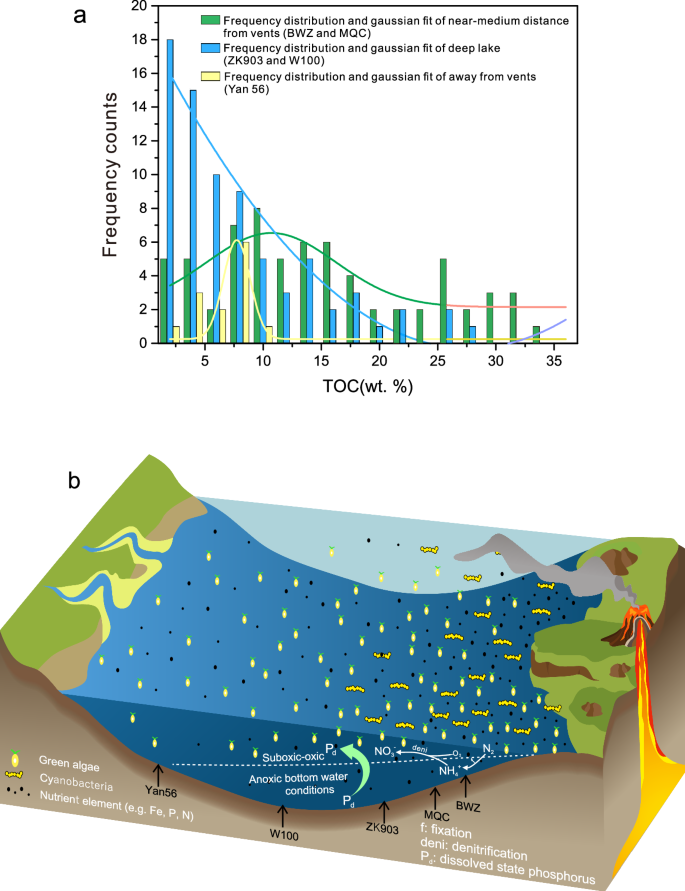

a TOC content for sites along a proximal-to-distal transect (i.e., from BWZ to Yan56) relative to the volcanic center located on the southwestern margin of the North China Craton. The locations of the wells and outcrop are shown in Fig. 1; b Model of nutrient element migration and redox conditions during volcanic eruptions of the Chang 7 Member in the Ordos Basin. Near the volcanic center, the level of anoxia in the lake basin increased, and nutrient P was recycled into the water column.

Increased water column anoxia is related to the enhancement of productivity42,43. The TOC content exhibits a sharp decline from sites proximal to the volcanic center (BWZ and MQC) to those located more distally (Yan56) (Fig. 5a). This decrease in TOC is not attributed to an increase in sedimentation rates (Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4). Interestingly, BWZ, despite having the highest Zr/Al ratio, also records the highest TOC levels (Fig. 4). In addition, a positive correlation between the δ13Corg of airborne ash-rich interval and TOC is observed (Supplementary Fig. 8), and unrelated to Al content from terrestrial sources Supplementary Fig. 8), indicating the increase in productivity leads to a decrease in the availability of dissolved carbon dioxide in the water body44,45.

The degree of anoxia in the sediment porewaters increased with Fe input. Observations through electron probe microanalysis (EPMA) reveal abundant Fe elements in volcanic ash layers (Supplementary Fig. 6). These Fe elements enter the water column in two forms: as salt substances covering the surface of volcanic ash (formed through post-eruption physical and chemical processes)46, which dissolve entirely in water as Fe2+ within hours to days5,47,48; and as iron-bearing glass shards and mineral particles that dissolve in the water over longer timescales49. After volcanic ash deposition, O₂ oxidizes Fe2+ into Fe3+, forming Fe(OH)3 precipitates, leading to rapid depletion of O2 in the volcanic ash layers and underlying sediments50. When the thickness of volcanic ash layers exceeds 3 cm, O2 in the volcanic ash layers and underlying strata can be entirely consumed51, resulting in the development of anoxic porewater conditions.

With increases in productivity and Fe inputs, oxygen consumption of sedimentary organic matter in the water column increased, leading to intensified anoxia in sediment porewaters and the overlying water column52,53,54. Iron speciation and framboidal pyrite size studies have revealed that bottom waters at Yan56 were suboxic55. The high productivity of the water column was related to volcanic inputs of P. The large amount of P in the water column was due to a combination of direct ashfall and P carried by streams into the lake basin within a few years of the eruption56. From BWZ to MQC to Yan56 (i.e., toward the NE region of the Ordos Basin), the content of volcanic ash gradually decreases (Fig. 5b), and thus the P carried in the volcanic ash should have also decreased. However, P/Al ratios show a gradual increase toward the NE (Fig. 4), a pattern that we attribute to reductive release and migration of P under anoxic conditions52,57. This process redistributed phosphorus throughout the basin, ultimately promoting higher organic carbon sinking fluxes (Fig. 5). This trend correlates precisely with the frequency of volcanic ash layers from high to low occurrence (Fig. 4), indicating that volcanic eruptions controlled watermass redox conditions and cyanobacterial distributions58.

Regional-scale volcanic eruptions also have the potential to affect climatic conditions. The gradual decrease of K/Al ratios from BWZ to Yan56 indicates enhanced chemical weathering toward the NE region of the Ordos Basin (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 5). The local climatic conditions following eruptions are considered to have become cooler and drier, correlating with weak chemical weathering in the SW region of the basin21. Unlike megavolcanic eruptions, which can profoundly influence Earth-surface climatic and environmental conditions (e.g., end-Permian Siberian Traps, end-Triassic Central Atlantic Magmatic Province)1,59,60,61, regional-scale volcanic eruptions are unlikely to cause mass extinctions. However, we have shown that lacustrine environmental conditions can be rapidly changed by the input of large amounts of nutrient elements such as P, N, and Fe10, thereby affecting the diversity and productivity of the autotrophic community (Fig. 5). Analysis of Upper Cretaceous volcanic ash-bearing shale indicates a rapid rise in post-eruption productivity10. Bacterial proliferation in lakes is generally stimulated by volcanic activity, and cyanobacteria levels in streams have also been observed to spike substantially60. Our study shows the coevolution of environmental perturbation and biological response. Ultimately, We argue that regional-scale volcanic eruptions through geological history may have been an important factor controlling paleoenvironments and carbon sequestration in lakes61.

Materials and methods

Sampling

In order to study the effects of volcanic ash on biological cycles and organic matter fluxes, we selected the BWZ and MQC sections in the Tongchuan area of the Ordos Basin. The BWZ and MQC outcrop sections were sampled, from which a total of 61 black shale samples were collected (Supplementary Fig. 1). Centimeter-scale samples were collected from BWZ-02, MQC-41, MQC-54, MQC-59, and MQC-64 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Samples BWZ-02, MQC-41, MQC-59 and MQC-64 contain layers of airborne volcanic ash of varying thickness. For each of these layers, three samples were taken: two above the volcanic ash layer and one below. MQC-54 contains water-borne volcanic ash, from which 12 samples were collected at centimeter intervals. The purpose of this sampling strategy was to ascertain the impact of volcanic ash of varying thickness and type on productivity and plankton community composition. Data including TOC, major and trace elements, δ13Corg and δ15Nbulk, were compiled for the Yan56, W100, and ZK903 wells from refs. 55,62, ref. 63, and ref. 64, respectively.

Palynological analysis

A total of 24 samples were used for palynological analysis. Each 50-g sample was smashed into pieces less than 1.0 mm in diameter and treated with HCl (30%) for 24 h and HF (40%) for 2 days in succession. A total of 200 identifiable grains (minimum grain diameter = 5 μm) was counted in each sample. These grains include: (1) granular AOM, (2) benthic algae, (3) gelified particles, (4) transparent ligno-cellulosic fragments, (5) charcoal, (6) resin particles, (7) cuticle, (8) spores, (9) pollen, (10) green algae, (11) cyanobacteria, and (12) fungi. All samples, slides, and stubs numbered are housed in the School of Earth Science and Technology, Southwest Petroleum University, Chengdu, China.

Microscopic observations

Detailed petrological observations were made on 17 volcanic ash/tuffaceous sandstone samples. A Leica microscope, which has transmitted light, reflected light, and fluorescence, was used for palynological observation and photography. Scanning electron microscopy was performed on an FEI Quanta 650 FEG ESEM of the volcanic ash layer and the shale above and below the tuff. The natural cross-section of the sample was observed in high vacuum mode with an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. The experiment was conducted in the School of Earth Science and Technology, Southwest Petroleum University, Chengdu, China.

Line scan and mapping scan based on EPMA

To obtain the volcanic ash layer and its elemental changes above and below, the samples were argon ion polished using a three-ion-beam cutting instrument (Leica EM TIC 3X) prior to analysis, and backscatter images, line scans, and area scans were obtained by electron microscopy analysis analyze. To obtain the micro in situ distribution of element carbon (C), we used gold to coat the samples. Elemental analysis of selected areas was further carried out using backscattered electron (BSE) images obtained by electron probe microanalysis (EPMA). Using a JXA-8100 electron probe, 15.0 kV accelerating voltage of 10.00 (s/point), the sampling interval of the line scan is 10 μm, with the sampling interval of the area scan of 1.2 μm. The experiment was performed in the State Key Laboratory of Oil and Gas Reservoir Geology and Exploitation, Chengdu University of Technology, China.

Major- and trace-element analyses

The whole-rock major- and trace-element testing of 62 black shales was completed at Guangzhou ALS Minerals-ALS Chemex. Prior to analysis, the rock powder samples were fully dissolved using an HNO3-HF acid mixture. Trace-element concentrations were measured by ICP-MS (Agilent Technologies 7700 Series); other elements, such as Ca, Mg, Fe, Mn, Al, Ti, Na, and K, were measured by ICP-OES (Perkin Elmer Optima 5300 V).

Organic carbon, sulfur, and nitrogen contents

The total organic carbon (TOC) and total sulfur (TS) contents of the shale were measured using a LECO CS225 elemental analyzer, after decarbonatization with hydrochloric acid. The repeatability of samples is consistently within 0.05 wt%. The experiment was conducted in the State Key Laboratory of Oil and Gas Reservoir Geology and Exploitation, Southwest Petroleum University, Chengdu, China.

The total nitrogen (TN) content of samples was measured on carbonate-free powder using a Vario Macro Cube elemental analyzer (EA, Elementar, Hanau, Germany) in the State Key Laboratory of Biogeology and Environmental Geology (BGEG) at China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), per the protocol of Song et al.65. About 50 mg of tungsten trioxide were packed into a 35 × 35-mm tin capsule. The measured nitrogen contents were used to calculate whole-rock TN based on the weight ratio of the pre-digestion sample to the acid-insoluble residue. Standard deviations for nitrogen contents are <0.05 wt% (1σ) based on replicate analyzes of multiple samples. Thus, the analytical precision of TN measurements was always better than 0.05 wt%.

Organic carbon isotopes

Organic carbon isotopes (δ13Corg) were analyzed at the State Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources, China University of Geosciences (Wuhan). Organic carbon was separated by treating samples repeatedly with hot, concentrated HCl and HF to dissolve carbonates and silicates, and the acid-insoluble residue was separated using heavy liquids and washed to neutrality before recovering the organic carbon for isotopic analysis. The organic carbon isotope composition of the generated CO2 was measured on a Finnigan MAT 251 mass spectrometer according to the procedure of Shen et al.66. All isotope data are reported as per mil (‰) variation relative to Vienna Pee Dee belemnite (VPDB) standard. The analytical precision is better than ± 0.1‰ for δ13C based on replicate analyses.

Bulk nitrogen isotopes

For bulk nitrogen isotopic analyses (δ15Nbulk), the analytical procedure followed that of Song et al.65. Ground carbonate-free powder (40–80 mg) was mixed with V2O5, sealed in a tin capsule, and combusted at 1020 °C, and the generated CO2 in the outflow gas mixture was absorbed by an alkali lime trap. Nitrogen isotope results are reported using the standard δ notation as deviations from the δ15N composition of atmospheric N2 (δ15NAIR = 0‰). Standard reference materials USGS40 (δ15NAIR = ‒4.52‰) and IAEA-N-2 (δ15NAIR = +20.3‰) were used for δ15N calibration with a precision better than ±0.5%. Analysis of a 10 mg V2O5 blank (Thermo Scientific, Cambridge, UK, PN 33837510) yielded no detectable N-isotope signal.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses