Wildlife’s contributions to people

Introduction

Nature’s contributions to people (NCP) — the benefits and disadvantages of nature for people’s quality of life1 — are increasingly recognized in international fora and target-setting across public and private sectors. In the past decade, the science underpinning policy and monitoring for NCP-related targets has rapidly advanced, particularly in modelling ecosystem functions and services to enable the mapping of crucial benefits such as climate-change mitigation, hazard regulation, water purification and pollination, from local to global scales2,3,4. However, mapping these benefits for rapid decision-making has obscured decades of research on how community structure supports ecosystem function, including the roles of wildlife and individual species’ presence or abundance3,5. In most target-setting and monitoring efforts, maintaining a given area or certain configuration of habitat is often assumed to be sufficient for managing NCP; the composition or abundance of species living in the habitat is not considered. This omission contributes to perceived trade-offs between conservation of wildlife — especially charismatic megafauna — and human well-being6. Species-centred conservation efforts are often seen as luxuries when weighed against meeting basic human needs. Although such tensions certainly exist and warrant substantial attention in conservation, wildlife are essential to NCP. Protecting ecosystems with declining or absent animal life will fail to ensure the continued flow of benefits to people.

Policy relevant to NCP often focuses on ecosystem-level functions that regulate water, climate or extreme events. Models representing such ecosystem functions are typically driven by ecosystem extent (for example, land use or land cover) and depict constant provision across any given ecosystem, regardless of the resident species7. As such, the mounting evidence of wildlife’s importance in maintaining ecosystem structure and function is often excluded from models and monitoring plans that inform conservation decisions. However, widespread loss of animals from ecosystems is already resulting in dramatic disruptions and alterations to plant communities8, which can disrupt ecosystems as much as, or more than, stressors such as climate warming and nutrient pollution9. Given that an estimated 48% of vertebrate species globally are in decline10, the extinction of ecological interactions and resulting ecosystem functions is a serious concern — often occurring well before extinctions of a population or species11. As implementation of conservation targets such as the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) accelerates, understanding the consequences of managing nature without explicitly considering wildlife is crucial, particularly for policymakers and managers.

In this Perspective, we assess the evidence for wildlife’s contributions to people (WCP) — that is, how wildlife provide and directly or indirectly support NCP. We focus on non-domesticated vertebrate wildlife that inhabit land, freshwater and oceans. Although definitions of wildlife include additional important taxa, such as invertebrates and plants12, we focus on how vertebrate species contribute to human well-being because the conservation value of vertebrates often depends on their being perceived as charismatic. This focus on vertebrate wildlife is not intended to indicate that vertebrates are more important for WCP than other taxa, or that policies promoting WCP should use this definition of wildlife. We discuss how wildlife is essential in delivering NCP, and how existing policies and strategies might fail to deliver their goals if they focus only on ‘nature’ as a shorthand for ‘vegetation’ or ‘habitat’. We identify future directions for monitoring, modelling and spatial planning research to better represent the wide range of WCP and to inform conservation policy and management — including activities concerned with protection, restoration or recovery, and sustainable use of species and ecosystems.

NCP in conservation policy

A disconnect exists between ecosystem-focused international conservation policies that increasingly incorporate NCP, and species-level targets for wildlife conservation, which typically do not consider NCP. For example, 11 of the 23 GBF targets include language on enhancing or maintaining NCP or ecosystem services. Target 11 specifically focuses on NCP, and targets 8 and 12 include measurable indicators of NCP (climate regulation and recreation, respectively). Most of the proposed GBF indicators for these targets focus on ecosystem extent and connectivity, geographically defined management status such as protected areas, or the magnitude of threats such as invasive species, pollutants and water stress13. Target 4 addresses the sustainable management of wild species and human–wildlife conflict, but only targets 5 and 9 explicitly recognize the value of wildlife to people. However, both targets 5 and 9 are focused only on use values (target 9’s guidance cites nutrition, food security, medicines and livelihoods as examples, and target 5 is concerned with ensuring that wildlife populations are not threatened by use and/or trade in their products). Importantly, no targets capture the regulating roles of wildlife in ecosystems. Similarly, biodiversity targets, indicators, performance standards and reporting requirements increasingly include a strong focus on NCP for business (the Science-Based Targets Network), investors (the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures), and nongovernmental organizations and multilaterals (for example, the World Bank, the InterAmerican Development Bank and the Asian Development Bank). However, for all these entities, species-focused targets are either disconnected from NCP targets or are absent entirely14,15.

In limited cases, some species-focused frameworks, such as the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS)16, recognize the essential roles of wildlife species in NCP. For example, CMS target 11 includes species’ contributions to water supply, quality and regulation; disaster risk reduction; climate regulation; cultural services; and socio-economic benefits including food — all of which contribute to people’s health, livelihoods and well-being. However, the indicator for CMS target 11 is vague (“trends in delivery of ecosystem services directly dependent on migratory species”16) and does not identify how specific ecosystem services should be tracked, which makes this target difficult to implement. Although CMS target 11 allows flexibility for services of interest to be defined locally, little guidance is provided for identifying wildlife-dependent services or for how to measure and manage wildlife’s contribution to these services. Further detail and guidance when incorporating WCP in policy making could help to direct conservation action and bridge the disconnect between policies focused on NCP and those focused only on wildlife, in turn strengthening both policy types.

Recognizing WCP within NCP

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) identifies 18 types of NCP grouped into three categories: material, nonmaterial and regulating17. Building on the concept of ecosystem services, the NCP approach emphasizes the importance of including diverse and under-represented knowledge systems (such as traditional ecological knowledge) in assessments of human–nature relationships18.

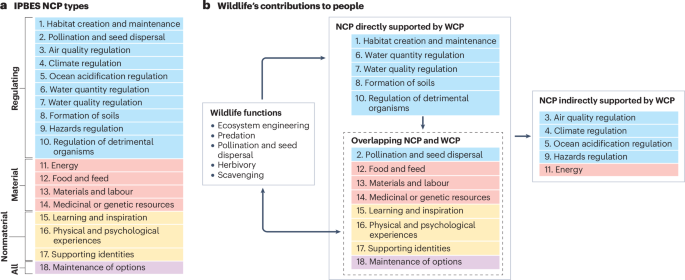

WCP comprises the numerous roles performed by wildlife that support the 18 NCP types, as well as some roles that are already recognized as NCP (Fig. 1). These roles (from the functional to the inspirational) can each be mapped to one or multiple NCP. Wildlife directly support 12 of these NCP through material, nonmaterial and regulating contributions, and arguably support the remaining NCP indirectly through shaping the ecosystems that provide these contributions (Fig. 1). Material WCP include food from game and fish; materials and labour associated with fur, skins and other animal products (for example, the live-animal and aquarium trade); and medicinal resources. Nonmaterial WCP underpin experiences, identity and learning from the use (hunting, fishing) or non-use (watching, knowing) of wildlife. Regulating WCP are mediated by ecosystem engineering and trophic functions performed by wildlife, which can affect regulating contributions directly (for example, beavers building a dam that regulates the flow of water) or indirectly (such as birds and monkeys dispersing the large seeds of hardwood tree species that store more carbon). The NCP type ‘Maintenance of options’ (the concept that nature, including wildlife, might contribute in unknown ways to future generations) leaves open possibilities for contributions from wildlife that are not yet fully understood.

a, The 18 NCP types described in IPBES 2019 (ref. 17) are classified as regulating, material or nonmaterial. b, Each of these NCP types is either directly or indirectly supported by wildlife functions. In some cases, WCP and NCP overlap as wildlife’s contributions are already recognized as NCP. WCP can contribute to NCP positively and/or negatively (indicated by arrows). For example, predation can positively affect the material contribution of food production by controlling agricultural pests and consequently increasing crop yields, or it can negatively affect this contribution through livestock depredation. Maintenance of options, which spans all three NCP categories, was not documented in the review of evidence, although wildlife undoubtedly contribute to this NCP type.

As with NCP, WCP can be positive or negative. Positive material contributions (such as food from hunting) and nonmaterial contributions (such as learning and inspiration from whale-watching) can be threatened by the unsustainable use or overexploitation of the contributing wildlife populations, which often drives species-focused conservation. Negative material contributions usually manifest as human–wildlife conflicts19 and negative nonmaterial contributions, including experiences or perceptions inducing fear or disgust20, can hinder the management of human–wildlife relationships and conservation of the species involved21.

Similar to NCP, WCP are more often characterized or quantified biophysically (that is, by their biological or physical values such as kilograms of meat or cubic metres of water) than valued (economically, culturally or otherwise)22. Furthermore, when wildlife are valued economically, the usual approaches are stated-preference methods such as asking people how much they are willing to pay to conserve wildlife23; these results are unlikely to represent wildlife’s full value if people are not aware of the diverse contributions these animals make to their well-being. When valued economically for their specific contributions, use values such as hunting dominate, although such analyses typically do not relate their estimates to wildlife population size and their results are, therefore, difficult to translate to policy and management24. To achieve holistic conservation that represents the diverse values of wildlife, we must recognize a broad set of WCP, and understand how WCP are delivered and maintained and how WCP support NCP.

Evidence for the value of WCP

Wildlife provide material, nonmaterial and regulating contributions through various mechanisms, both as WCP that are recognized as NCP and as WCP that directly and indirectly support NCP (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 1). Maintenance of options, an NCP type that spans all three categories, is undoubtedly supported by conserving wildlife species, but little evidence is available on this topic specifically.

Material contributions

Material contributions from wildlife fall into three of the four types of material NCP defined by IPBES17: food and feed, materials and labour, and medicinal and genetic resources. The fourth type in this category, energy, could be supported directly by wildlife via dung, but given that the use of dung is more common for livestock than for wildlife, this type is not included here.

Food and feed

In terrestrial systems, the majority of evidence for wildlife’s material value relates to bushmeat and hunting of wildlife, where terrestrial wildlife provide substantial nutrition to humans25,26,27,28,29,30. For example, bushmeat (frequently defined as meat derived from terrestrial, vertebrate species) contributes up to 80% of the animal protein consumed in some rural regions of West and Central Africa and is a common source of protein and nutrition for groups throughout the globe29. However, bushmeat is also a frequent concern for human health because of its potential as a vector for zoonotic disease transmission (a negative regulating contribution)27,29,31. Marine and freshwater wildlife provide similar, well documented material benefits: humans consume over 2,500 freshwater fish species32, and marine species provide nutrition in the form of both calories and important macronutrients and micronutrients33,34,35.

Materials and labour

In addition to being consumed, harvested bushmeat can be sold to provide financial contributions28,29, which are particularly important to rural communities in which increased cash flow can help to alleviate poverty27,29. The relative importance of these financial contributions varies among communities, but the benefits derived from sales are often less important than the nutritional benefits of harvest27. Similarly, marine and freshwater fisheries provide livelihoods, revenue, employment and food security and subsistence36. For example, marine fisheries globally provide the equivalent of about 203 million full-time jobs37. Additionally, people harvest wildlife to use animal parts (such as reindeer velvet, snake venom, musk, pelts, furs, leathers and baleen) for a vast range of material purposes35,38. The global trade of wildlife products is important for local and national economies, and includes harvests worth millions of dollars annually27, but it can lead to unsustainable or illegal harvesting of wildlife that reduces the provision of other WCP.

Medicinal resources

Wildlife provides materials for traditional medicinal purposes in many cultures26,27,38. For example, up to 76 species harvested as bushmeat are used for medicinal purposes via consumption, and in Brazil alone 51 species are consumed for the prevention or treatment of disease26.

Nonmaterial contributions

Nonmaterial contributions of wildlife include all three of the IPBES nonmaterial NCP types17: physical and psychological experiences (such as recreation, tourism, and physical and mental health); learning and inspiration; and supporting identities. Despite a historical emphasis (in mostly Western literature) on human–wildlife conflict, attention has been increasing on beneficial WCP in all of these types39.

Physical and psychological experiences

Wildlife affect people both physically and psychologically. Health is the most documented nonmaterial WCP, including negative contributions caused by human–wildlife conflict such as injuries from animals, risks to safety and/or security, and negative emotions resulting from those real or perceived threats19,39,40,41. However, wildlife also infuse human life in positive ways; human–wildlife interactions have been associated with psychological benefits such as pleasure, relaxation, a sense of connection, and even improvements in cognitive functions such as attention restoration and stress reduction42. For birds43, ungulates25, and large carnivores44, recreation and tourism are the most frequently documented positive WCP, whereas the directionality of the contribution for human-habituated species depends upon whether the species is considered a nuisance, which can negatively affect tourism, mental health and safety45. Economic analysis suggests that the physical and psychological benefits of wildlife (from expenditures on nonmaterial experiences such as wildlife viewing, hunting and fishing) outweigh the costs (of control and damage) by more than an order of magnitude46.

Learning and inspiration

Wildlife feature in artwork and music across millennia (especially in pre-modern and non-Western cultures)47,48 and direct interactions with wildlife are important learning and/or spiritual experiences49,50. Many cultures consider animals to be important literal and metaphorical teachers51, and pedagogical research suggests that animals can provide complex learning support52. Furthermore, biomimicry of animals has inspired many product and service innovations53.

Supporting identities

For communities worldwide, at local to national scales, wildlife are central to peoples’ identities and to ways of understanding the world and its relationship with humans. In these communities, identities are deeply intertwined with species54 and connections often centre around food (for example, acquiring bushmeat can signal social status; harvesting salmon is a lynchpin of identity for some Indigenous peoples)27,28. Also common is a kinship-centric understanding of animals (that animals and humans are kin, or related as family)55.

Regulating contributions

One foundational function of wildlife within natural systems is ecosystem engineering, in which individuals or populations substantially alter the physical environment. Wildlife also regulate ecosystems through their trophic dynamics, which are crucial to maintaining natural processes on which humans rely. These two functional roles directly enable six of the ten regulating NCP types17: habitat creation and maintenance (which in turn could indirectly enable the remaining regulating NCP types); formation, protection and decontamination of soils and sediments; pollination and dispersal of seeds and other propagules; regulation of detrimental organisms and biological processes; water quantity regulation; and water quality regulation (although the latter two are based on one particular well-studied taxon: beavers)56.

Ecosystem engineering

Evidence for ecosystem engineering focuses primarily on contributions from large-bodied herbivores. For example, terrestrial herbivores in grassland ecosystems contribute to the formation of bare ground and soil compaction, which results in landscapes that promote high biodiversity and increased plant community function and productivity57,58. Many species also contribute to the distribution and cycling of key nutrients and resources, such as nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon57,58. Through construction of dams in streams and rivers, beavers improve water retention, decrease flow velocity, and in some cases improve water quality by trapping sediments and nitrates (although dams can also concentrate ammonia and methyl mercury)56. In oceans, megafauna such as whales contribute to ocean mixing, which not only facilitates nutrient cycling within water, but also moves nutrients throughout layers of the oceans35. Given that ecosystem engineers are often considered keystone species in communities and ecosystems, further investigation of how these contributions affect people is warranted.

Trophic dynamics

Marine and freshwater trophic webs support nutrient transfer and secondary productivity, and maintain the water quality of aquatic ecosystems critical to humans33,35,59. In terrestrial systems, wildlife affect plant community health through seed dispersal60, and large herbivores in particular promote nitrogen availability, plant regeneration, plant diversity and primary productivity57,58. Many birds and some mammals within trophic webs are pollinators that support agricultural production and plant reproduction in natural systems, increasing fruit and seed production by 63% on average beyond insect pollinators61. These taxa often also suppress crop pests, and other predatory wildlife suppress different pest species (for example, in urban areas)43,45,62.

Predation and competition provide density regulation of herbivores, mesopredators and other prey, which cascades to regulate ecosystems45,62 and reduce the prevalence of diseases that pose a risk to humans44,62. The consumption of carcasses and other biological waste by scavenging species adapted to neutralize disease loads, such as vultures, reduces the risk of exposure to disease and biohazards posed by wildlife44,62. Increased wildlife density near human communities can increase the risk of zoonotic disease transmission45,46; however, increased diversity of wildlife is sometimes associated with a dilution effect that lowers disease risk63. The net effect on disease burden resulting from regulating contributions of wildlife versus wildlife-borne disease transmission is a major knowledge gap64, but biodiversity loss has been established as a key driver of disease risk65.

Indirect contributions of wildlife

Wildlife also affect other NCP indirectly. Regulating contributions from ecosystem engineering and trophic dynamics make indirect positive and negative contributions to people. Negative contributions are often more visible to people, especially those resulting in human–wildlife conflicts. Invasive wildlife cause various negative regulating contributions, disrupting food webs and natural functioning of ecosystems, and consequently affect NCP66. Additionally, conflict can involve native wildlife that trample or otherwise damage crops19,25,45, compete with livestock grazers19,25, predate livestock38,44, and cause loss of life and property25,42,45. However, many of these risks can be mitigated with management; for example, when livestock are adequately protected, intact populations of large carnivores keep wild herbivores in check and have been shown to improve crop yields, pasture biomass and profitability44.

Positive indirect contributions can be harder to observe than negative contributions but might be more prevalent. The indirect contributions of pollinators are well documented: pollinators support material NCP, such as food and medicine from pollinated wild plants, as well as nonmaterial NCP such as psychological well-being gained from wildflowers67. Conceivably, any NCP type that originates primarily from the vegetative components of a particular ecosystem (for example, regulation of climate; regulation of hazards and extreme events; and even the material contribution of energy production) could be indirectly attributed to wildlife for their role in maintaining that ecosystem (browsers maintain grasslands by preventing woody encroachment57, seed dispersers maintain the diversity of trees in a forest60, and predators prevent barrens caused by excess herbivory in kelp and other aquatic ecosystems59). Other NCP depend less on the composition or condition of the ecosystem; floodplains, for example, store flood waters regardless of the plant species present, and certain recreation activities rely only on open space in an ecosystem. However, functions often depend on the structure of the ecosystem17, which is created and maintained in part by wildlife.

Nutrient and carbon cycling are key examples of indirect contributions of wildlife that are often absent from ecosystem modelling. Nutrient cycling is essential for the maintenance of ecosystems (and the array of benefits they provide), and is enhanced by birds (through translocation and deposition of nutrients)43, carnivores (especially scavengers, which influence decomposition)62, and even commensal or habituated species in urban environments46. Large herbivores substantially reduce soil phosphorus and litter cover, which is thought to promote biodiversity through increased structural complexity at the landscape scale57, and predators reduce soil erosion by preventing overgrazing by herbivores44. Similarly, the indirect contributions wildlife make to carbon sequestration can be substantial. Although wild animals contain only 0.3% of the carbon held in global biomass, their effects on ecosystems cause the amounts of carbon in plants, soils and sediments to vary by orders of magnitude more, owing to foraging, trampling or other disturbance, organic matter deposition, seed dispersal, predation, nutrient translocation and other functions68.

Biases and limitations

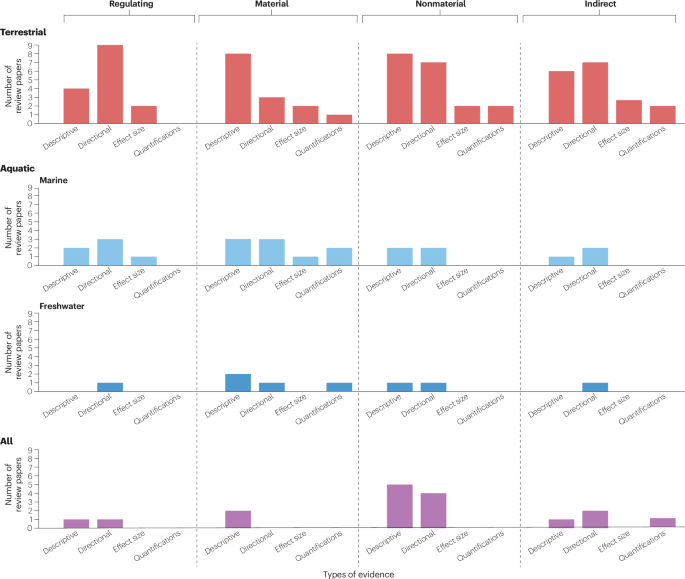

Understanding of WCP is influenced by multiple biases and limitations, including in the views and expertise of the authors (see Positionality statement). Overall, the literature is biased towards easily studied charismatic or familiar species, high-income countries and Western worldviews (Supplementary information). Taxonomic, geographic and cultural biases have resulted in inconsistent evidence quantifying the contributions, and therefore value, of wildlife to people (Fig. 2) (Supplementary Table 1).

The relative amount of evidence (number of review papers detailing evidence) for WCP from the 42 reviews cited in Supplementary Table 1 is displayed. Evidence is categorized by realm of study (freshwater, marine, terrestrial or all), the type of contribution to people (indirect, material, nonmaterial or regulating), and the type of evidence. Types of evidence include quantifications (for example, dollar amounts), effect sizes (for example, percentage), directionality of relationship (positive or negative) or descriptive. Information presented in this figure is derived in part from the information presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Taxonomic bias

Many gaps in understanding reflect taxonomic biases towards larger, terrestrial mammals and species that appeal to humans. Large-bodied wildlife have been discussed at length in an NCP context25, whereas the contributions of smaller animals are less studied or viewed more negatively (for example, they may be labelled as pests or vectors). Available evidence for WCP covers birds43,69, ungulates and other large mammalian herbivores25,57,58, and carnivores and scavengers44,62, the vast majority of which are terrestrial mammals. By contrast, taxon-specific evidence for reptiles or amphibians is scarce. Furthermore, although the effect size and directionality of some dynamics has been evaluated — for example, herbivore impacts on plant communities58 and bird impacts on a variety of functions43,69 — quantitative syntheses are missing for many contributions (Supplementary Table 1). The contribution of ecosystem engineers is a basic ecological function, but the linkage between these species and their contributions to people’s well-being via ecosystem health and function is little understood35,58. For nonmaterial contributions specifically, mammals comprise the taxonomic group for which nonmaterial WCP are most often studied, followed by reptiles and birds39. Although the contributions of marine filter feeders, other secondary consumers and whales have been reviewed33,35, the contributions of terrestrial wildlife to people remains the primary focus of research. In terrestrial systems, wildlife literature usually focuses on vertebrates, but most of the NCP literature for pollination and pest control pertains to insects70. Further studies are needed on the other contributions of invertebrates and on underrepresented wildlife taxa.

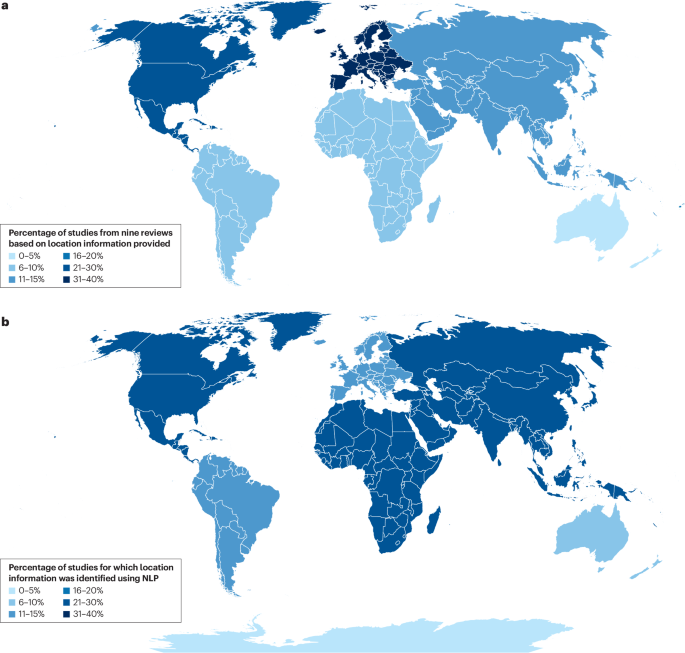

Geographic bias

Geographic biases comprise an overrepresentation in documented cases of WCP from North America and Europe (Fig. 3, Supplementary information). Additionally, regional reviews of WCP exist for the Americas and Europe71,72,73,74, but are scarce or non-existent for other regions. These biases reflect language hegemony, as many studies outside Europe and North America are not published in English; for example, most studies in Latin America and the Caribbean are published in Spanish and Portuguese, and in the format of theses or local journals75. The under-representation of studies in low- and middle-income countries, especially Latin America, is a well documented research gap.

a, Of 42 reviews assessing WCP (Supplementary Table 1), 9 published locational data of their included studies (1,111 studies in total). The distribution of these studies is shown as a percentage of the total at the continental level. b, For the remaining 33 reviews that did not publish locational data of their included studies, title scanning for geographic information (such as country or continent names, states, cities, parks, river basins, oceans or coastlines) using natural language processing (NLP; Supplementary information) identified at least continent-level locations for 1,486 of 3,991 unique references. The distribution of studies for which locations could be identified is shown as a percentage of the total (1,486) at the continental level.

Additionally, non-English language publications are likely to include valuable alternative perspectives, as relationships with wildlife and benefits from their contributions in many countries and regions might not be adequately captured by English-language terminology or concepts. For example, kincentric perspectives on human–wildlife relationships might not translate directly into English terms76,77. Although meta-analyses limited to English-language studies are not necessarily biased (as has been shown, for example, in fields such as conventional medicine78,79), the inclusion of publications in other languages is an important area for further research and review.

In addition to the geographic bias in study region, the authors of the cited reviews (Supplementary Table 1) were affiliated with institutions predominantly from Europe (30% of studies with at least one author affiliated), the USA (23%), Canada (9%) and the UK (9%). Larger review efforts undertaken by IPBES include geographically representative and diverse author teams, and several past assessments address themes that relate to WCP but do not focus exclusively on wildlife66,80,81. Identifying further research gaps pertaining to WCP within IPBES assessments could help to choose research priorities while accounting to some extent for this geographic authorship bias.

Cultural bias

Intertwined with taxonomic and geographic gaps and biases are cultural biases. One aspect of cultural biases includes variation in how research is approached in different regions, which will influence trends such as a transition from the prevailing research focus on negative human–wildlife relationships to increasingly holistic framing that better incorporates positive human–wildlife relationships. Cultural biases also include deeply rooted patterns in how people think; for example, categories of species form the basis for taxonomy in Western science, whereas relationships between species are central to many Indigenous knowledge systems82. Such bias is associated with epistemological limitations, because ecologists and social scientists often conceptualize nature as separate from culture and, therefore, humans as distinct from wildlife. Ecosystem services assessments and evaluations of NCP could promote an inherent anthropocentric bias, in which humans are perceived as having more agency than wildlife, and wildlife are perceived as providing solely instrumental value to humans. An alternative epistemic approach would be to embrace a pluralistic view of human–nature relationships that better incorporates other ways of knowing, including Indigenous worldviews, kincentric perspectives and relational values in human–nature interactions83,84,85. This expanded perspective has both ethical and practical implications: it would increase inclusivity and justice in wildlife research, and would make space for perspectives that in many contexts improve the sustainability of human–nature relationships86,87.

WCP in policy and management

Loss of wildlife will, in the long term, lead to declines in WCP and consequent harm to people — especially those in disadvantaged communities, who often depend heavily on nature. Even when WCP (or other NCP) can be substituted for built infrastructure, technology and other manufactured capital, these solutions are often more expensive, less resilient and have fewer co-benefits than WCP. Given the interdependence of wildlife and their habitats, managing for biodiversity or NCP without accounting for WCP risks undermining the long-term achievement of both these goals. Underestimating the importance of material and nonmaterial WCP to the well-being of communities living in or near protected areas has often led to poorer biodiversity outcomes86, which has supported the trend towards community-led conservation (Box 1). However, even in inclusive conservation contexts, misunderstanding the regulating roles species have in ecosystems could lead to management decisions that interfere with system dynamics. In some cases, restoring tenure, access, harvesting and management rights will need to be balanced with correcting past mismanagement that has had cascading and disproportionate consequences (such as the sea urchin barrens resulting from the removal of sea otters; Box 2). Moreover, failing to account for the degree to which WCP support NCP could create incentives to conserve ‘empty’ ecosystems, preventing ecosystem conversion but not addressing poaching, overexploitation, pollution or other risks to wildlife.

In the worst cases, failure to manage for WCP could undermine ecosystem stability in unpredictable and possibly catastrophic ways. Tipping points are gaining increasing attention88, but these abrupt and potentially irreversible changes in ecosystems are typically attributed to physical drivers and sometimes nature degradation but not defaunation. For example, the 2023 Global Tipping Points Report does not mention ‘wildlife’ (or ‘animal’ or ‘fauna’) in its summary report88. These omissions indicate a lack of appreciation for wildlife’s role in supporting ecosystem resilience and buffering tipping points. The majority of the Earth system tipping points identified in the report (12 of 22) are elements of the biosphere in which wildlife are central to ecosystem function, such as coral reefs (the closest to tipping), tropical forests, boreal forests and kelp forests. Wildlife’s contributions to maintaining function, such as seed dispersers in tropical forests89,90 and megafauna in boreal forests and tundra91, could prevent these ecosystems from crossing tipping points.

The GBF seeks to avoid these catastrophic outcomes of biodiversity loss by putting society on a nature-positive path to 2030 and beyond. However, even if the GBF targets are met13, risks to WCP remain. Within the GBF, wildlife continues to be treated as separate from ecosystem function and services, and the targets typically address ecosystem elements of biodiversity (such as structure and extent) separately from species elements (such as richness or population abundance). If wildlife and ecosystems are not linked, decision-makers are likely to miss opportunities for synergy and to use scarce conservation resources inefficiently. New targets are not necessarily required, but recognizing the connections between wildlife and ecosystems is vital to achieving conservation goals for biodiversity and NCP. Scientific insights into wildlife’s contributions must be harnessed and embedded into global biodiversity policies (such as the GBF, CMS and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)) to support NCP.

Explicitly connecting wildlife with benefits to people helps policy-makers and managers to implement multi-objective planning by demonstrating how objectives depend on wildlife health, not simply on maintaining their habitats. This connection has been partly integrated in instruments such as community-based natural resource management (Box 1), although tradeoffs between positive WCP such as wildlife harvesting or viewing and negative WCP such as threats to safety or food security remain a challenge (Boxes 2 and 3). Accounting for WCP explicitly, especially WCP that are often overlooked (for example, regulating contributions by vertebrates) can enhance conservation policies and programmes.

To fully include WCP in policy and management, the mechanisms by which wildlife deliver benefits to people must be clearly identified and communicated. Currently, limited tools for monitoring and modeling at scale hinder understanding of WCP and how wildlife management can support or enhance benefits to people. Addressing these limitations is essential to provide the necessary information to effectively manage wildlife’s crucial contributions.

Outlook

A wealth of evidence supports the importance of WCP. However, although research on these contributions is strong, current modelling and monitoring capabilities are insufficient, limiting WCP integration into conservation policy and management. Improving monitoring and modelling capacity is a priority for future work, alongside a focus on social science and the science–policy interface.

Advances in the spatial and temporal resolution of satellite observing systems, in combination with advanced analytical techniques, could support wildlife detection and monitoring92,93. Advances in LiDAR, radar and hyperspectral observations would substantially improve global vegetation mapping94 and have already provided valuable insights for understanding wildlife–vegetation interactions95, which could be associated with outcomes for WCP and NCP. The upcoming NASA ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar (NISAR) and the hyperspectral Surface Biology and Geology (SBG) missions might further advance these efforts96. Satellite advances are complemented by emerging techniques for capturing wildlife movement and habitat use, including acoustic sensors and camera traps, environmental DNA (eDNA, genetic material that animals and other organisms shed in habitats), and new approaches in telemetry that aim to build an ‘internet of animals’97. However, these innovations will still require data from long-standing ‘analogue’ wildlife-monitoring programmes, which rarely receive enough attention or investment to validate measurements of wildlife abundances and habitat use at scale. Citizen science networks, which can empower local communities and other stakeholders through participatory monitoring, can also support wildlife monitoring; Namibia’s nation-wide biodiversity atlas (‘Atlasing in Namibia’) provides one example. As with so many ecological efforts, wildlife-monitoring programmes have historically been biased towards high-income countries in the Northern Hemisphere98; a representative approach to wildlife monitoring that preferentially includes countries and species that have typically been under-represented is a research priority. A lack of species-level data has contributed to the underrepresentation of wildlife in NCP approaches, but artificial intelligence methods could establish relationships between satellite data with increased sensing capacity and limited (yet indispensable) field data to enable the inclusion of wildlife in policy and planning at increasingly larger scales99,100,101.

Advances in observation capabilities will help to characterize and monitor wildlife, but modelling advances are needed to link habitat quality, wildlife populations and people. Conceptual frameworks for linking biodiversity, ecosystem function and ecosystem services often use broad definitions of biodiversity (such as species richness)6, and incorporating WCP into these models requires understanding how species presence or abundance affects function. Additional empirical work is needed to quantify these relationships between the abundance and magnitude of function (most research to date reports only on the directionality of the relationship; Fig. 2). Although mainstream ecosystem service models such as InVEST102,103 and ARIES104,105 do not model wildlife dynamics and their effect on ecosystems, the inclusion of biodiversity modelling in NCP models could improve NCP predictions106; for example, including population dynamics in Earth systems models107 and using network theory to incorporate food-web interactions into ecosystem service modelling7. Next-generation approaches such as the Madingley model108,109 and ecosystem-based fisheries models (such as Atlantis110, ECOPATH/ECOSIM111 and ‘mizer’112) represent species and functional group effects on ecosystem functions and services, and have already been used to model various WCP and values to people (such as revenue and jobs). One challenge for this field of research is to reconcile the spatial and temporal scales of existing models and the population distributions, dynamics and functional impacts on ecosystems that underpin NCP. A second challenge is representing the cultural values and potential disservices from wildlife in models. However, mainstreaming the integration of wildlife populations and dynamics into widely used ecosystem service models could improve predictions of NCP and is critical to ensure we do not undervalue the role of wildlife in NCP decision-making.

Beyond technological and modelling advances, translating insights from the social sciences on WCP could ensure that wildlife conservation is fair and inclusive, accounting for multiple differing perspectives. Valuation of WCP varies across contexts owing to diverse cultural values and beliefs113. For example, in certain regions, the same wildlife species might evoke both affection and aversion21, and some invasive species are championed by animal rights movements while conservation scientists advocate for culls114. Integrating social justice into wildlife conservation and management policies is an important research frontier85,115. Empirical analysis is required on distributive justice concerns for the positive and negative effects of WCP — including on the poverty, health and wellbeing of local communities116, and among different societal groups (such as gender, age, socio-economic status, race and ethnicity). Similarly, increased attention and further research is needed to understand the procedural justice dimensions underlying how decisions about managing and conserving wildlife are made — by whom, and for whose benefit117. The disparities in power between those who shape the wildlife conservation agenda, those who allocate resources, and those who bear the cost of negative WCP warrants further exploration.

People holding Western worldviews, which strongly separate humans and wildlife55, have much to learn about WCP from the longstanding and reciprocal relationships with wildlife found in Indigenous and traditional knowledge systems, many of which view the right to enjoy benefits from wildlife118,119,120 as being linked to the responsibility to care for these species and their habitats84,121. Well-developed Indigenous and traditional approaches that integrate ethics to manage their relationships with wildlife (in ways that maintain WCP) could guide Western current and future practices121. Assessing evidence in multiple languages, especially those not globally dominant owing to historical colonization (that is, languages other than English, Spanish, French or Portuguese), could help to capture perspectives from diverse linguistic and cultural contexts, potentially moving beyond anthropocentric and dominating views rooted in certain historical and religious paradigms49. Including diverse languages and worldviews might enable an increasingly pluralistic and inclusive understanding of human–wildlife relationships.

Finally, translating knowledge on WCP to action relies on its concepts successfully crossing the science–policy interface, beyond the conservation community. Policy-makers have shown some willingness to integrate a WCP approach; for example, 2023 guidance from the US Department of the Interior on restoring bison and prairie landscapes explicitly recognizes bison’s regulating contributions to maintaining prairie ecosystems122. For this awareness to become widespread, the capacity to implement monitoring and modelling advances will also need to be expanded. Many countries’ national biodiversity strategies and action plans for implementation of the GBF lack even basic spatial information on their local biodiversity, despite the increasing global availability of relevant datasets.

NCP aims to reveal the invisible benefits of nature and has achieved great traction and uptake in policy, business and finance. However, wildlife often remain invisible in NCP. Healthy ecosystems depend on diverse and healthy wildlife to regulate and otherwise sustain ecosystem function. Human well-being depends on wildlife in multiple ways beyond the consumption or existence value of animals. Strengthening the case for WCP will help to garner widespread and enduring support for wildlife conservation.

Responses