XFEL crystallography reveals catalytic cycle dynamics during non-native substrate oxidation by cytochrome P450BM3

Introduction

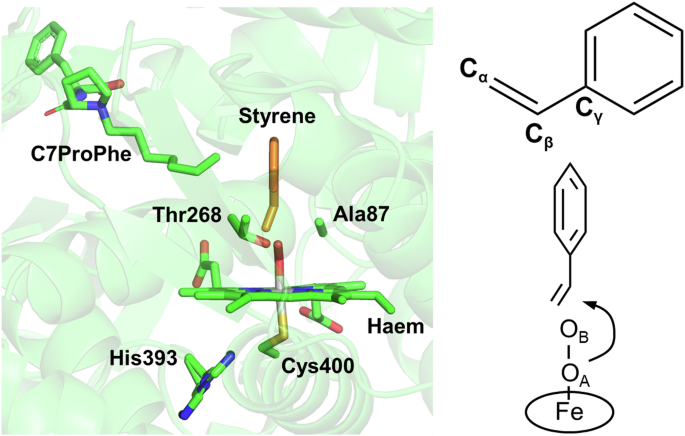

Cytochrome P450 enzymes (P450s) comprise a vast superfamily of haem-containing oxidoreductases involved in many important biological processes, from steroid and lipid biosynthesis to xenobiotic degradation1,2,3. P450BM3 isolated from Priestia megaterium catalyses the hydroxylation of long-chain fatty acids and has been demonstrated to possess some of the highest turnover frequencies (TOFs) amongst all reported P450s, making it an attractive starting point for the development of artificial biocatalysts capable of synthesising useful chemical compounds4. Attempts at redesigning P450BM3 using protein engineering methods, such as site-directed mutagenesis and directed evolution, have been made in an endeavour to control the stereoselective oxidation of non-native substrates5,6,7. As an alternative, a chemical approach utilising pseudo substrates (decoy molecules), which are substrate mimics that are slightly smaller than the natural fatty acid substrates, has been developed for manipulating P450BM3 reactivity. When P450BM3 misrecognises and binds a decoy molecule, a cavity is left within the active site, which serves as a reaction space for non-native substrates. So far, a variety of decoy molecules have been developed8, and this approach has proven effective for changing P450BM3 into a versatile biocatalyst for the oxidation of challenging non-native substrates, for example the gaseous alkane methane, which possesses a high energetic barrier for oxidation8,9,10. A combination of mutagenesis with decoy molecules, such as N-enanthyl-L-prolyl-L-phenylalanine (C7ProPhe), has enabled the epoxidation of styrene with high enantioselectivity11,12. However, the mechanism of how the orientation of the substrate at the active site is controlled during progression of the catalytic cycle remains poorly understood.

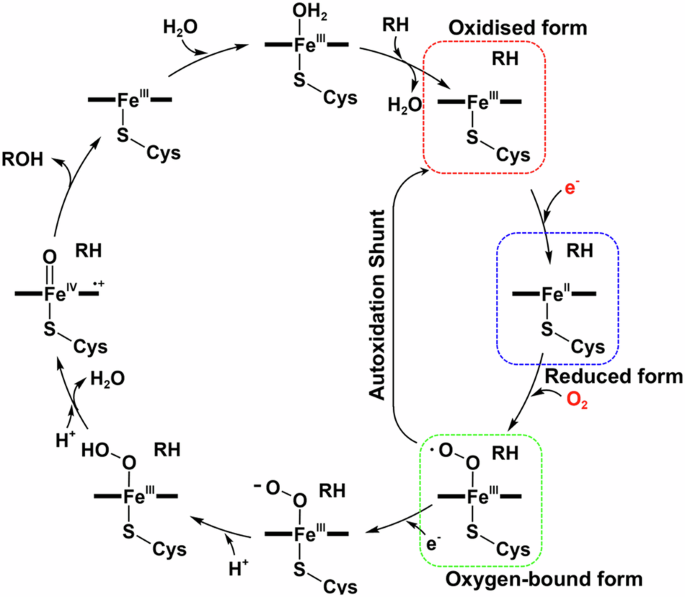

The P450 catalytic cycle, as shown in Scheme 1, is complex, traversing through various stages, each possessing a unique electronic configuration and oxidation state1. When P450 in its oxidised resting state binds a substrate, haem-bound water is dislodged, changing haem from a hexa- to a penta-coordinated state. This raises the haem redox potential, facilitating the formation of the reduced form13,14,15, which can bind O2, the oxygen source for substrate monooxygenation. By accepting a further electron and two protons, the oxygen-bound form is converted to the oxoferryl (FeIV=O) porphyrin π-cation radical (Compound I), which ultimately oxygenates the substrate. In most P450s, the substrate-binding site forms a deep cavity that buries haem deep within the protein, isolating it from the solvent or lipid membrane. Substrate entry and product release require large conformational changes, and as with many other P450s, P450BM3 undergoes an open-to-close conformational transition upon substrate binding, which has been extensively investigated4. However, subsequent structural dynamics are challenging to capture, leaving us with static structures of the substrate-bound form that are often insufficient for characterising the intermediate conformational states that contribute to the efficiency and specificity of this enzyme. For example, the crystal structure of oxidised P450BM3 in complex with a fatty acid substrate (palmitoleic acid) showed the hydroxylation sites of the alkyl chain to be 7 Å away from the haem iron16,17. NMR paramagnetic relaxation measurements indicated that the reduction of haem is accompanied by a structural change with a 6 Å movement of the substrate into a position closer to haem18. In addition to these studies on the native substrate, an analysis by us on oxidised P450BM3 in the presence of a decoy molecule revealed that styrene (non-native substrate) binds distant from the haem iron in a catalytically unproductive orientation12. Consequently, information on the structural dynamics of key intermediates is of the utmost importance in advancing the rational control of non-native substrate oxidation by decoy-containing P450BM3.

General catalytic cycle of P450 monooxygenases. Oxidised, reduced, and oxygen-bound forms are highlighted by red, blue, and green dashed lines, respectively. RH: substrate.

Thus, we set out to analyse intermediate structures of P450BM3 in the presence of decoy molecules and styrene. Focus was placed upon the structural dynamics occurring during the first half of the catalytic cycle (from the oxidised resting state to the oxygen-bound form), due to this stage being decisive in how the decoy, styrene, and O2 enter the haem active site and successively form the reaction space. However, the structural analysis of the oxygen-bound form of P450BM3 has been obstructed by numerous technical challenges. Foremost, P450BM3 is prone to auto-oxidation as a result of its low redox potential compared to other P450s, rendering these intermediates too unstable to capture by X-ray crystallography14. Furthermore, the haem iron is readily reduced by X-ray generated electrons, causing the formation of aberrant coordination geometries and thus reducing the veracity of obtained structures19. Consequently efforts to determine the true structure of the active site of P450BM3 via X-ray crystallography have been greatly impeded.

To overcome aforementioned challenges, two potential solutions were explored. Firstly, by utilising the F393H mutant of P450BM3, the rate of auto-oxidation was retarded whilst maintaining enzymatic activity. Phe393 is located near the proximal ligand Cys400, and substitution of this residue with His elevates the redox potential of haem, though the underlying mechanism remains unclear14,20. Secondly, employing an X-ray free-electron laser (XFEL), which can generate femtosecond X-ray pulses of high brilliance, damage-free structural analysis, known as the “diffraction before destruction” principle, was enabled21,22. By combining these two solutions, we succeeded in determining the structures of the oxidised, reduced, and oxygen-bound forms of P450BM3 F393H in complex with a decoy molecule (C7ProPhe) and styrene. Analogous structures of P450BM3 F87A/F393H were also determined. The F87A mutation exhibits notable (R)-enantioselectivity for styrene epoxidation in the presence of decoy molecules11,12. Thus, comparing the structural dynamics of F393H and F87A/F393H should enable clarification of the origin of enantioselectivity during the reaction. Structural analysis at high resolutions (1.50–1.85 Å) demonstrated that the position and orientation of styrene are controlled in a stepwise fashion through conformational changes associated with the reduction of haem and subsequent O2 binding. Moreover, the obtained binding orientation of styrene in the oxygen-bound form serves to clearly explain the high (R)-enantioselectivity of styrene epoxidation by the mutation at Phe87. The current findings serve to demonstrate the importance of dynamics in catalysis, enriching our understanding of the molecular mechanism of non-native substrate oxidation by P450BM3 in the presence of decoy molecules. These results may provide a structural basis for the protein engineering of P450BM3 to obtain desirable biocatalysts.

Results

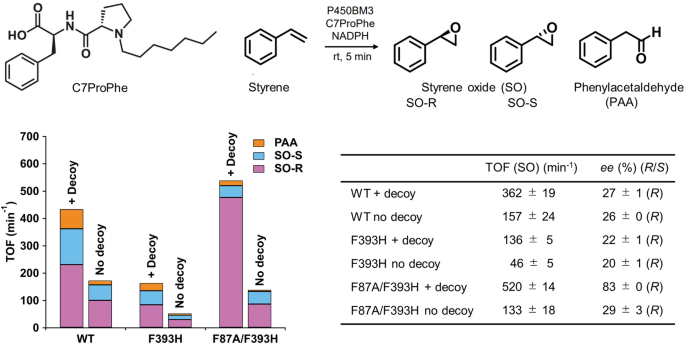

P450BM3 enzymatic activities

Two variants of the P450BM3 haem domain (F393H and F87A/F393H) were employed for structural analysis. The substitution with histidine at Phe393 was necessary to stabilise the fully reduced enzyme as well as the oxygen bound form. The effect of these mutations on the enzymatic activity in the presence and absence of decoy molecules (C7ProPhe) during styrene oxidation was investigated and compared to the wild-type (WT) enzyme. For the oxidation of styrene by P450BM3 in the presence of C7ProPhe, the vinyl group of styrene was the reactive functional group. The TOFs and enantiomeric excesses (ee) for the oxidation of styrene by P450BM3 are summarised in Fig. 1. Employing GC-MS, three styrene oxidation products, namely (R)- and (S)-styrene oxide (SO-R and SO-S, respectively) and phenylacetaldehyde (PAA), were detected. As previously reported, C7ProPhe substantially increased the TOF, producing styrene oxide as the main product, with the WT enzyme generating an excess of the (R)-enantiomer11. The same trend was also observed for the F393H and F87A/F393H variants in the presence of C7ProPhe, although the TOF of F393H (136 min−1) was only about a third of the WT (362 min−1). Interestingly, introducing the F87A mutation into F393H quadrupled the TOF (520 min−1), exceeding even the WT enzyme. As expected, F87A/F393H exhibited a much higher (R)-enantioselectivity (83% ee) than both WT (27% ee) and F393H (22% ee). These results indicate that the F393 mutation does not substantially interfere with the action of the decoy molecule nor the enantioselective effect of the F87A mutation.

Reaction conditions: P450BM3 (1 μM), C7ProPhe (100 μM), styrene (saturated), NADPH (5 mM), at room temperature for 5 min. The TOF and ee values are presented as mean ± s.d. (n ≥ 3 independent experiments).

Crystal structures of the oxidised form

Microcrystals of the oxidised form of P450BM3 F393H and F87A/F393H were prepared by cocrystallisation in the presence of styrene and C7ProPhe. UV–visible absorption spectra of the microcrystals are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1A, D. The Soret band of F393H and F87A/F393H were observed at 416 nm with a shoulder at around 395 nm. The blue shift of the Soret band (typically observed around 390 nm) is indicative of a Type I shift4, which is caused by the dislodging of haem-bound water upon substrate binding, inducing transition of the haem iron from a ferric low- to high-spin state. The observed split of the Soret band suggests presence of haem as a mixture of its hexa- and pentacoordinate states, hinting at only partial expulsion of haem-bound water. The presence of pentacoordinate haem is further supported by the presence of an absorption peak around 647 nm, which is characteristic of a ferric high-spin state.

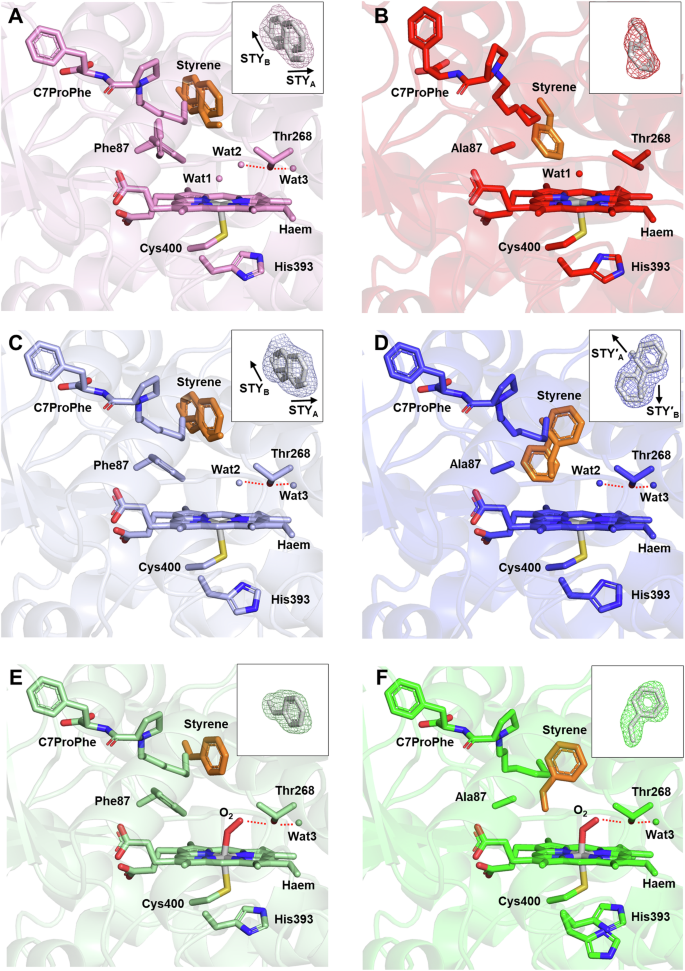

The active site structure of F393H in the oxidised form is shown in Fig. 2A. The electron density map shows conformationally heterogeneous binding, with styrene adopting two different orientations at the active site (Supplementary Figs. 2A inset, S2A, C). The orientation of styrene with the vinyl group directed towards haem (STYA) had an occupancy of approximately 0.3, whilst the occupation of styrene with its vinyl pointing away from haem (STYB) was slightly lower at 0.2. Multiple conformations were also observed for the side chain of Phe87, which was either rotated towards (occupancy: 0.7) or away (occupancy: 0.3) from haem. Apart from haem-bound water (Wat1, occupancy: 0.4) two further water molecules were found in proximity to haem. Wat2 (occupancy: 0.7) and Wat3 (occupancy: 1.0) were hydrogen-bonded to Thr268 in the I-helix. Comparison of the occupancies of Wat1 and Wat2 with those of the side chain of Phe87 revealed that the dual conformation of Phe87 may correlate with the partial expulsion of Wat1, although this does not appear to be associated with the two orientations of styrene (vide infra). In F87A/F393H, styrene was located closer to haem, likely due to elimination of the bulky Phe87 side chain (Fig. 2B). However, the electron density of styrene was still somewhat poor (Fig. 2B inset, Supplementary S2B, D), suggesting some flexibility of styrene binding in this mutant (occupancy: 0.7). Wat1 was present with an occupancy of 0.6, whereas neither Wat2 nor Wat3 could be observed.

The oxidised (A, B), reduced (C, D), and oxygen-bound (E, F) forms of F393H (A, C, E) and F87A/F393H (B, D, F) are depicted. Haem, Cys400, Thr268, C7ProPhe, styrene, O2, and the side chains of Phe87, Ala87, and His393 are shown as stick models. Styrene is highlighted in orange. Water molecules close to haem are depicted as small spheres. Hydrogen bonds are represented as red dotted lines. The inset in each panel shows the polder omit map of styrene represented as a mesh contoured at 3.0σ (A–D) and 4.0σ (E, F). The resolutions of the XFEL data are 1.80 Å (F393H) and 1.85 Å (F87A/F393H) for the oxidised form, 1.60 Å (F393H and F87A/F393H) for the reduced form, and 1.50 Å (F393H and F87A/F393H) for the oxygen-bound form.

Both F393H and F87A/F393H had similar overall structures (root-mean-square deviation (RMSD): 1.04 Å), except for the F-, G-, and I-helices, which displayed notable differences (Supplementary Fig. S3A). The F- and G-helices were more distant from the haem active site in F87A/F393H than in F393H. Consequently, the channel for substrate entry remains open in F87A/F393H (Supplementary Fig. S4). The I-helix adopted an irregular, kinked form in F87A/F393H, where the main chain C=O of Ala264 was hydrogen-bonded to the side-chain OH (not the amide nitrogen) of Thr268 (Supplementary Fig. S3C), as seen in P450cam23,24. In contrast, in F393H, the kink of the I-helix was eliminated, and Wat2 and Wat3 lay between the C=O group of Ala264 and the OH group of Thr268 (Supplementary Fig. S3B). No multiple conformations were observed, except for Phe87 in the active site.

Crystal structures of the reduced form

Crystal structures of F393H and F87A/F393H in the reduced form were obtained by reducing microcrystals of the oxidised form with dithionite. Reduction of haem for both F393H and F87A/F393H was confirmed from the Soret band at 410 nm by UV-visible spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. S1B, E). Whilst reduction did not change the overall structure in F393H, in F87A/F393H the F- and G-helices moved towards the substrate binding site and the kink of the I-helix was relieved (Supplementary Fig. S5). Consequently, the major structural differences between F393H and F87A/F393H in the oxidised form were alleviated in the reduced form (RMSD: 0.09 Å). In response to protein conformational changes, the haem active site structure changed in F87A/F393H. The haem active site structures of F393H and F87A/F393H in the reduced form are shown in Fig. 2C and D, respectively. Wat2 and Wat3 also appeared in F87A/F393H, and the binding mode of styrene was restricted to two orientations in F87A/F393H, as identified in F393H. The two orientations were designated STY′A and STY′B, as shown in Fig. 2D inset and Supplementary Fig. S6. The occupancies of styrene were 0.3 (STYA) and 0.6 (STYB) for F393H and 0.5 (STY′A) and 0.4 (STY′B) for F87A/F393H. In F393H, Phe87 adopted a single conformation in the reduced form, while styrene retained its two orientations. This suggests that the dual conformations of Phe87 in the oxidised form were not correlated with the distinct binding modes of styrene. In the reduced forms of F393H and F87A/F393H, haem was pentacoordinated and Wat1 was no longer present.

Crystal structures of the oxygen-bound form

Preparation of the oxygen-bound form was technically most challenging. We established a procedure for its preparation in microcrystals of P450BM3, as described in ‘Methods‘. In brief, a slurry of microcrystals in the reduced form was washed using a deaerated solution in an anaerobic glove box to remove excess dithionite. Then, the microcrystals were transferred out of the glove box and kept at −12 °C to prevent auto-oxidation during soaking into an oxygen-containing cryoprotectant solution. UV-visible absorption spectra of the oxygen-bound form yielded absorption peaks at around 358, 419, and 557 nm (Supplementary Fig. S1C, F), characteristic of the oxygen-bound form of P45014,25. These spectra remained stable for at least 1 h at temperatures below −12 °C, demonstrating that the oxygen-bound form did not undergo auto-oxidation.

The overall structure of the oxygen-bound form was similar to that of the reduced form, including the I-helix (Supplementary Fig. S7) (RMSD: 0.07 Å for F393H; 0.07 Å for F87A/F393H). However, local structures surrounding O2 and styrene were affected by O2 binding to haem. The haem active site structures in the oxygen-bound form of F393H and F87A/F393H are shown in Fig. 2E and F, respectively. In both F393H and F87A/F393H, O2 was hydrogen-bonded to Thr268, causing Wat2 to disappear. The omit (Fig. 2E, F insets) and 2Fo−Fc maps (Supplementary Fig. S8) show clear electron densities for O2 and styrene. The respective occupancies of O2 and styrene were 0.7 and 0.9 in F393H and 0.8 and 0.9 in F87A/F393H. The bond lengths and angles between the haem iron and O2 are summarised in Supplementary Table S1. Coordination of O2 to haem was less tilted in F87A/F393H, resulting in a smaller Fe-OA-OB angle and a longer hydrogen bond distance between O2 and Thr268 than F393H. It is noteworthy that the haem-O2 geometry determined using XFEL is damage-free. In fact, synchrotron crystallography with an X-ray dose of 2 MGy confirmed the X-ray photoreduction effect, resulting in a more bent Fe-O-O angle and an elongated Fe-O bond length for F87A/F393H (Supplementary Fig. S9, Table S2).

The most dramatic effect of O2 binding was seen in the orientation of styrene. In the active site of F393H, O2 pushed Phe87 away by ~0.3 Å (Supplementary Fig. S10A), which changed the interaction between Phe87 and styrene, causing styrene to exclusively adopt the STYB orientation. However, in F87A/F393H the orientation of styrene orientation was restricted to STY′B, due to STY′A being destabilised by the proximity of O2 to the phenyl group of styrene (Supplementary Fig. S10B). Consequently, the vinyl group of styrene was directed to O2 in F87A/F393H, but to the opposite side in F393H. The distance from the terminal carbon of the vinyl group of styrene to the proximal oxygen atom of O2 was 3.2 Å in F87A/F393H but extended to 7.7 Å in F393H. Furthermore, in F87A/F393H there was a cavity near styrene, whereas in F393H the cavity was occupied by the vinyl group of styrene (Supplementary Fig. S11). The terminal methyl group of C7ProPhe was near the phenyl group of styrene, suggesting that C7ProPhe tethers the phenyl group of styrene via CH-π interactions.

Discussion

The P450 catalytic cycle is a multistep process that requires the input of molecular oxygen, two reducing equivalents, and two proton equivalents to form the catalytically active species (Scheme 1). Despite extensive investigation into the structural dynamics of substrate binding to P450BM3 in its resting state (oxidised form), capturing the full range of structural alterations occurring during subsequent steps of the catalytic cycle has remained technically challenging. A major reason is the extreme instability of most catalytic intermediates. For example, the oxygenated intermediates are highly susceptible to auto-oxidation, resulting in the formation of inactive oxidised species. A further technical hurdle for the crystallographic analysis of P450s is the propensity of the haem iron to absorb free electrons generated by X-ray irradiation, thereby altering its oxidation state. This adversely affects the coordination geometry of haem and, in turn, the bound ligand. In the present study, we devised methods for the preparation of P450BM3 microcrystals in three different stages constituting the first half of the catalytic cycle, and employed XFEL to determine their damage-free structures.

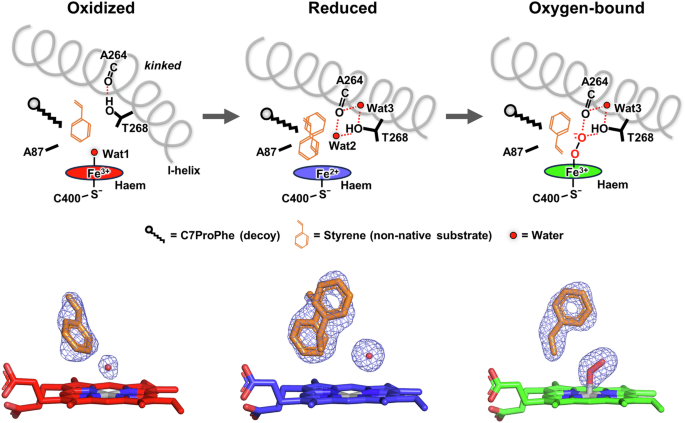

Notably, the structures of P450BM3 F87A/F393H displayed remarkable dynamics, demonstrating that, although the position and orientation of styrene immediately after binding are catalytically unproductive, the conformation of styrene is optimised in stages through reduction of haem and O2 binding (Fig. 3). In the oxidised form of F87A/F393H, styrene exhibits a disordered active site orientation, due to the substrate channel remaining open and the substrate binding site being relatively wide with a kinked I-helix. However, transition from the oxidised to the reduced form closes the substrate channel and relaxes the kinked tension on the I-helix through the placement of two water molecules (Wat2 and Wat3). As the substrate binding site narrows, the degrees of freedom of styrene are constrained to two orientations. Upon O2 binding there are no significant changes in the protein conformation, however, Thr268 releases Wat2 and instead forms a hydrogen bond directly with O2. Accompanied by these subtle changes, the orientation of styrene became unified in a catalytically productive conformation.

The electron densities (polder omit map) of styrene, O2, and water molecules (Wat1 and Wat2) near haem are also shown below the schematics. The maps are contoured at 3.0σ for the oxidised and reduced forms and at 4.0σ for the oxygen-bound form. The resolutions of the XFEL data for the oxidised, reduced, and oxygen-bound forms are 1.85, 1.60 and 1.50 Å, respectively.

Comparison between F87A/F393H and F393H in the oxygen-bound form clarified the structural basis for the increased oxidative activity and (R)-enantioselectivity of styrene oxidation by the F87A mutation (Fig. 2E, F). In the F393H variant, the vinyl group of styrene is positioned pointing away from haem, and is thus too distant to be oxidised. Styrene requires large scale reorientation at the active site for the oxidative reaction to occur. In contrast, in F87A/F393H the vinyl group of styrene is positioned much closer to haem, allowing styrene to be oxidised by the active oxygen species with only minor adjustments. The enhanced oxidative activity by the F87A mutation can thus be explained by the accessibility of styrene to the haem active site. The (R)-enantioselectivity of styrene oxidation by the F87A mutation is also reasonable, considering the structure of the oxygen-bound form. Suzuki et al. recently reported the mechanism of the enantioselectivity of the styrene oxidation by P450BM3 using a Mo-oxo complex as a model of Compound I12. According to their X-ray structures and density functional theory calculations, the negative ∠O-Cα-Cβ-Cγ dihedral angle implies a preference for (R)-enantioselective oxidation. In the present study, the ∠OA-Cα-Cβ-Cγ dihedral angle in the oxygen-bound form of F87A/F393H was −47.7° (Fig. 4), which is in agreement with the interpretation of the Mo-oxo complex results.

The structure in the left panel corresponds to Fig. 2F, but is rotated by 90° along the vertical axis. The right panel shows a schematic of the geometry of styrene and O2 bound to the haem iron.

A further important detail that deserves discussion is the proton shuttle pathway, which has been extensively studied in P450cam23,24. Two protons are required for the cleavage of haem-bound O=O, and two ordered water molecules, as well as highly conserved Asp251 and Thr252 (Glu267 and Thr268 in P450BM3), have been identified in P450cam as part of the proton delivery system. These catalytic water molecules appear only in the oxygen-bound form and are anchored by Thr252 in the I-helix. In contrast, the oxygen-bound form of decoy-containing P450BM3 exhibits a different hydrogen bonding network (Supplementary Fig. S7B, C) (Supplementary Note S1). Although Wat3 is lodged between Ala264 and Thr268 in the relaxed I-helix, there are no other ordered water molecules around Thr268, which donates a hydrogen bond directly to O2. The lack of the second catalytic water molecule implies that the proton delivery network could not be optimised for the P450BM3 system in the presence of the decoy and styrene (non-native substrate), and thus the reactivity of this engineered P450BM3 could be further improved by optimising the proton delivery network to activate haem-bound oxygen.

In general, P450 enzymes can be broadly classified into two main classes based on substrate specificity26,27. The first class comprises P450s that exhibit a strong preference for a single substrate. Such P450s are predominantly found in plants and bacteria, and also include those involved in steroidogenesis in animals. P450BM3 is classified within this group. The second class is defined by broad substrate specificity, mostly comprising P450s involved in xenobiotic metabolism in vertebrates. In regard to the first class, two oxygenated intermediate structures (P450cam23,24 and P450eryF28) have been elucidated by synchrotron X-ray analysis, and one ferric hydroperoxide intermediate structure (P450 12129) has been reported using time-resolved XFEL. Basically, these analyses did not detect any large-scale conformational changes in the substrate orientation, as these P450s possess high substrate recognition specificity and well-defined structures for substrate-enzyme interactions via hydrogen bonding. In contrast, P450BM3 in the presence of decoy molecules exhibited notable conformational changes associated with optimisation of the styrene orientation, a process found to be redox- and ligand-dependent. One of the factors that made this possible could be the innate flexibility of the active site of P450BM3, which has been acquired through molecular evolution. This property enables P450BM3 to drive enantioselective reactions with a range of non-native, hydrophobic compounds through conformational alteration of the active site in conjunction with specially tailored decoy molecules. In a sense, the introduction of a decoy molecule effectively transforms P450BM3 from a highly substrate-specific class I P450 into a xenobiotic-metabolising class II P450, as demonstrated by the ability of the P450BM3-decoy molecule system to oxidise a wide variety of non-native substrates, such as styrene, benzene, and other small alkanes30,31.

In summary, by overcoming difficulties in capturing the true intermediate structures of P450BM3, we have elucidated how catalytic cycle dynamics control non-native substrate (styrene) binding in P450BM3. The F87A mutation to P450BM3 provides a space near haem for styrene to adopt an orientation facilitating higher oxidation reactivity and (R)-enantioselectivity. We emphasise that our data demonstrates how structural dynamics that occur during the catalytic cycle are important for determining enzymatic activity and enantioselectivity, and that structures of the oxidised state do not represent an accurate depiction of the catalytically active state of the enzyme, particularly for the positioning of substrate in the active site, as demonstrated for other haem enzymes29,32,33,34,35. By extension, this must also hold true for the xenobiotic-metabolising class of P450s. Although the work presented herein delivers a model for the structural dynamics of P450BM3, our experimental approach using XFEL for probing reduced and oxygenated intermediates is expected to work on a wide range of different P450s. It is worth noting that recent advances in serial synchrotron crystallography have made it possible to analyse haem pocket structures with a very low dose of around 100 kGy or less, making it a practical tool, provided that the coordination structure of haem is carefully considered36,37,38. The application of these latest techniques to intermediates of various types of P450s will provide a much needed understanding of enzyme and substrate dynamics at atomic resolutions, and guide the rational design of mutants or decoy molecules required to make this class of enzymes a more formidable biocatalyst.

Methods

Expression and purification of P450BM3

Full-length P450BM3 and the haem domain of WT, F393H, and F87A/F393H were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) and purified using a previously reported method12. The protein concentration was estimated via the pyridine haemochromogen method39 and adjusted for each experiment. Full-length P450BM3 was used to evaluate biocatalytic activity, whereas haem domain variants were used for spectroscopy and crystallography.

Evaluation of the biocatalytic activity of P450BM3 proteins

Reactions were performed according to a literature procedure12. The final concentration of all components of the reaction mixture was 2% DMSO, 0.5 µM full-length P450BM3, 100 µM C7ProPhe, saturated styrene, and 5 mM NADPH. The pH was maintained at 7.4 during the reaction by 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 100 mM KCl. After 5 min, the reaction was quenched and the products extracted into CHCl3. An internal standard (tetralin) was also added at this point. The organic layer was analysed via GC-MS (GCMS-QP2010 SE, Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a CycloSil-β column. TOFs and enantioselectivities were estimated from calibration curves generated from authentic samples. All biocatalytic reactions were performed at least in triplicate, and the TOF is expressed in units of (mol product) per (mol P450). GC-MS conditions were as follows: column temperature, 83 °C (25 min), 50 °C min−1, 200 °C (10 min); injection temperature, 250 °C; interface temperature, 200 °C; detector temperature, 200 °C; carrier gas, helium; split ratio, 5. Retention times of the products and internal standard were (R)-styrene oxide (13.1 min), (S)-styrene oxide (13.9 min), phenylacetaldehyde (15.3 min), and tetralin (21.8 min).

Crystallisation of P450BM3 in complex with styrene and C7ProPhe

Purified P450BM3 was dialysed into a styrene-saturated buffer composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 200 μM C7ProPhe and 1% v/v DMSO via spin centrifugation-dialysis. Protein solution concentrated to 10 mg mL−1 (50 μL) was mixed with reservoir solution (50 μL) containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 16–18% w/v polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000, and 120 mM MgCl2. Seed solution (0.1 or 0.2 μL), prepared using a reported procedure40, was added and the resulting solution incubated at 4 °C. Brownish homogeneous crystals of 30–70 μm in size were obtained in the sample tube. P450BM3 in these microcrystals was present in its oxidised form.

Preparation of P450BM3 microcrystals in the oxidised, reduced, and oxygen-bound forms

Sample tubes prepared in the previous section containing microcrystals of P450BM3 in their oxidised form were used. Crystallisation solution was replaced with a buffer solution containing 125 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 14% w/v PEG 8000, 60 mM MgCl2, saturated styrene, and 30% glycerol as cryoprotectant. The microcrystals adhered to the inner wall of the sample tube were detached using a plastic tip and suspended in the tube. To increase the microcrystal density on the mesh loop (described below), the contents of four tubes were pooled.

Microcrystals of reduced P450BM3 were prepared from aforementioned microcrystals of oxidised P450BM3 in a glove box (COY Laboratory Products Inc., USA) under anaerobic conditions. Cryoprotectant (3 mL) pre-saturated with styrene and degassed with N2 was prepared and stored on ice. 400 mM dithionite solution (1.5 mL) was also prepared and stored on ice. The sample temperature was maintained at 4 °C using a bath (Power BLOCK, Atto, Japan). Inside the glove box, 400 mM dithionite solution was diluted with cryoprotectant (final dithionite concentration 5 mM). The solution from the sample tubes containing the microcrystals was suspended and centrifuged (6200 rpm) for 10 s in a tabletop centrifuge (Petit Change, WakenBtech Co., Ltd, Japan) and the supernatant solution was removed and replaced with cryoprotectant solution containing dithionite. The solution in the sample tube was incubated for 1 h, whereafter it was replaced with N2-substituted cryoprotectant solution without dithionite (100 μL).

Oxygen-bound P450BM3 microcrystals were prepared from microcrystals of reduced P450BM3 under aerobic conditions. First, O2-saturated cryoprotectant solution (2 mL) was prepared by injecting O2 gas into a degassed cryoprotectant solution pre-saturated with styrene and stored on ice. Sample tubes containing microcrystals of reduced P450BM3, O2-saturated cryoprotectant, and a glass plate were placed on an XT freezing core (BioCision LLC, USA) that was precooled below −12 °C. The sample tube was centrifuged for 10 s, whereafter the supernatant was removed with a chilled tip. The O2-saturated cryoprotectant (40 μL) was added to the sample tube with a chilled microsyringe. The contents of the sample tube was gently suspended using a chilled tip, and incubated for 15 min. The condensed microcrystal suspension (20 μL) was taken from the sample tube with a chilled tip and transferred onto the glass plate on the XT freezing core. The suspension was gently stirred for 5 min with a mesh loop to ensure binding of O2 to P450BM3. Notably, maintaining a low temperature below −12 °C was crucial to prevent auto-oxidation of the oxygen-bound form. Consequently, the fixed-target X-ray data collection method at 100 K was chosen over the room-temperature data collection method using an injector device with liquid or viscous media. Microcrystals of P450BM3 in the oxidised, reduced, and oxygen-bound forms were collected with 600 μm mesh loops for spectroscopy (Protein Wave Co., Japan) or custom-ordered 2 × 2 mm mesh loops for crystallography (Supplementary Fig. S12) (Protein Wave Co., Japan). The microcrystals on the loops were immediately frozen in liquid N2 and stored in a Uni-puck (MiTeGen, USA) until further use.

UV–visible absorption spectroscopy

A goniometer was installed into the microspectrophotometer41. An empty mesh loop was used for spatial alignment of the probe light (Xenon flash lamp, Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan). The microcrystals on the 600 μm mesh loops were placed under a cryostream of N2 gas at 100 K. Baseline and dark spectra were recorded with and without the probe light, respectively, and UV–visible absorption spectra were measured, using the microspectrophotometer. The spectra were also measured under solution conditions using a quartz cuvette with a path length of 1 cm and a Nanophotometer-NP 80 (Implen) (Supplementary Fig. S1G–L). Purified P450BM3 was dissolved in 125 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.3) containing 80 µM C7ProPhe and 200 µM styrene. The protein concentration was 10 µM for the oxidised and reduced forms and 5 µM for the oxygen-bound form. The reduced form was prepared by adding sodium dithionite (final concentration: 100 μM) to the oxidised protein. The oxygen-bound form was prepared by mixing the reduced protein with the oxygen-containing buffer at 4 °C, and the measurement was performed immediately.

XFEL-based crystallography

Diffraction data was collected at BL2 EH3 of the SPring-8 Angstrom Compact Free Electron Laser (SACLA). 2 × 2 mm mesh loops were mounted on a goniometer using the automatic crystal exchanger system, SPACE. During data collection, microcrystals were maintained at 100 K under a steady cryostream of N2 gas. The X-ray beam (photon energy: 12.996 keV; number of photons: 7.7 × 1010 pulse−1; beam size at sample position: 4.34 (H) × 4.45 (V) μm) was attenuated to 60% using a 0.3 mm Al plate and scanned over the loop area at 10 Hz with a 50 μm shift between each shot. The still diffraction images were recorded using a CCD detector (MX300-HS, Rayonix, USA) with a sample detector distance of 150 mm. A data processing pipeline42 based on Cheetah43 was used for monitoring the hit images and tentative index rates during data collection. CrystFEL 0.9.1 was used for processing the diffraction images44, and the XGANDALF45 indexing method was selected. More than 10,000 indexed images were obtained for the oxidised, reduced, and oxygen-bound forms of F87A/F393H and F393H. Integrated intensities were merged by process_hkl in the CrystFEL suite. The crystals in all samples were in the P212121 space group with similar cell dimensions. A structure of WT P450BM3 (PDB ID: 6K58) was used as the starting model for structure refinement on PHENIX46. The atomic model was manually corrected using the programme Coot47. The partial occupancies of styrene, haem-bound O₂, water molecules, and Phe87 were determined through the following steps. Initial occupancy values for these molecules and the residue were obtained using the occupancy refinement function in phenix.refine. Subsequently, models with occupancy values varied in increments of 0.05 around the initial estimates were generated, and phenix.refine was run without occupancy refinement. The validity of the occupancy values was assessed based on the Fo – Fc maps and B-factors, and final occupancies were determined where no residual density appeared in the Fo–Fc map and the refined B-factors of the atoms in the target molecules and residue most closely matched those of the surrounding atoms. The final occupancy values were rounded to one decimal place. The electron density for styrene exhibited a complex shape in the oxidised and reduced forms (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S6), indicating two distinct orientations of its structure. Thus, for the modelling of styrene, various orientations were explored. After structure refinement with the first orientation of styrene, with optimisation of its partial occupancy, the second orientation was built using the Fo–Fc map and subjected to further refinement. The refined orientation, occupancy value, and B-factor of the alternative model were evaluated based on the fit to the polder omit map48, which was generated by omitting each of the two orientations. The real space correlation coefficients were computed from the final coordinates and the 2mFo–DFc maps using the validation tool (phenix.real_space_correlation) in PHENIX (Supplementary Table S3)46. The 2mFo–DFc maps were calculated without filling the missing reflections from the calculated structure factors. The asymmetric unit contained two monomers of P450BM3 (chains A and B). Although the structures of chains A and B were essentially the same (Supplementary Fig. S13, Table S1), the electron density of styrene in the oxidised form of F393H was poorer in chain A than in chain B, which prevented the modelling of the second orientation of styrene for chain A. Thus, all figures and active site geometries were calculated from the atomic coordinates of chain B. The statistics of the collected and structure-refined data are summarised in Tables 1 and 2. The diffraction precision index (DPI) was calculated on the online server49.

Synchrotron crystallography

Diffraction data of the oxygen-bound form of F87A/F393H was collected at BL32XU in SPring-8. The microcrystals of the oxygen-bound state were prepared using the same protocol as for XFEL-based crystallography. The small-wedge (10°) datasets were collected from 55 crystals on a mesh loop using an X-ray beam size of 10 × 10 µm. During data collection, microcrystals were maintained at 100 K under a steady cryostream of N2 gas. The dose was calculated using RADDOSE-3D50. Indexing, integration and merging were performed by XDS and KAMO51,52. The atomic model was refined by PHENIX46. The statistics of data collection and structure refinement are shown in Table 3.

Responses