ZHX2 inhibits diabetes-induced liver injury and ferroptosis by epigenetic silence of YTHDF2

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus (DM) due to the harmful effects of high glucose and fat levels in the body [1, 2]. It is estimated that around 25% of adults worldwide are affected by MASLD [3]. Diabetic individuals face a significantly higher risk ((sim)56%) of developing MASLD compared to non-diabetics, and it has been found that 70%–90% of MASLD patients also have DM or insulin resistance [4, 5]. Currently, the drugs used to treat diabetic liver injury, including MASLD, mainly consist of hypoglycemic and hepatoprotective medications. However, these drugs often exhibit limited therapeutic effects and notable side effects [6]. The underlying mechanisms behind the coexistence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and MASLD remain complex and not fully understood. Therefore, there is an urgent need to investigate the pathogenesis of MASLD in diabetic patients and identify effective targets for improving their overall health status and increasing survival rates.

Ferroptosis is a type of cell death that occurs due to iron accumulation and lipid peroxidation. This particular type of cell death occurs when there is dysfunction in the cystine-glutamate antiporter system (xCT or SLC7A11), depletion of glutathione (GSH), and inactivation of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) [7]. Recent research has shown that ferroptosis may contribute to the development of complications associated with diabetes mellitus, including kidney disease [8], osteoporosis [9], encephalopathy [10], cardiomyopathy [11], retinopathy [12], and MASLD [13, 14]. Studies have also demonstrated that inhibiting ferroptosis with liraglutide [15], puerarin [16], metformin [17], and sulforaphane [18] can improve MASLD in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D). Furthermore, overexpression of AGER1 has been found to alleviate liver injury in T2D mice by inhibiting ferroptosis [19]. These findings suggest that targeting ferroptosis may hold promise for therapeutic interventions aimed at managing MASLD in individuals with DM.

Zinc fingers and homeoboxes 2 (ZHX2) is a member of the ZHX family, known for its role in transcriptional regulation. It is first identified as a suppressor of murine postnatal alpha fetal protein [20]. Further research has shown that ZHX2 plays a crucial role in controlling gene expression during postnatal liver development [21, 22] and maintaining hepatic lipid homeostasis [23]. Notably, ZHX2 has been found to impede the progression of MASLD-HCC progression by blocking the uptake of external lipids [24]. Additionally, depletion of ZHX2 has been shown to worsen the condition of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) [25]. However, the potential involvement of ZHX2 in diabetes-induced liver injury has not been extensively studied.

The involvement of the transcription factor ZHX2 extends to both liver injury and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. This study aims to investigate the role and underlying mechanisms of ZHX2 in DM-induced hepatic damage. Our results indicate that elevated levels of ZHX2 effectively mitigate DM-induced liver injury while suppressing ferroptosis. Mechanistically, the increased expression of ZHX2 inhibits the transcription of YTHDF2, leading to an upsurge in GPX4 and SLC7A11 levels, which in turn impedes the progression of ferroptosis. Additionally, YTHDF2 recognizes m6A-modified ZHX2 mRNA and subsequently diminishes its expression. Collectively, these findings highlight the regulatory capacity of ZHX2 as a potential therapeutic target for attenuating DM-related hepatic injuries.

Materials and methods

Animals and experimental procedure

Male C57BL/6 mice, aged 8 weeks and weighing between 20–25 g, were obtained from the Animal Center of Sun Yat-Sen University. The animal experiments followed the guidelines set by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Southwest Medical University. After one week of adaptive feeding, the mice were randomly divided into three groups. The normal control group received a standard chow diet for 12 weeks. On the other hand, the DM group was fed a high-fat diet (HFD) throughout the entire experiment. Following 6 weeks on HFD, STZ injections (40 mg/kg/d, i.p.) were administered to both groups for five consecutive days. However, instead of STZ injections, citrate buffer was injected into the control group using an equivalent dose. Fasting blood glucose levels were measured in all mice after nine days. Mice that consistently exhibited blood glucose levels exceeding 16.7 mmol/L for three consecutive days were identified as diabetic mice. To conduct in vivo experiments involving ZHX2 overexpression, AAV9-ZHX2 (referred to as AAV-ZHX2) was injected via tail vein at a volume of 200 μL containing vectors with a concentration of 2 × 1011 vg per mouse after establishing DM models in mice for an additional four weeks. As a negative control group (AAV-NC), empty vector injections were given to another set of DM mice. The AAVs used in the study were prepared and purified by Genechem Co., LTD. (Shanghai, China).

Histological staining

The liver tissues were fixed in a solution containing 4% paraformaldehyde. Subsequently, they were processed and embedded into paraffin blocks. The resulting blocks were then sliced into sections with a thickness of 0.4 μm for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. For Prussian blue staining, we utilized the Prussian Blue Stain kit (ab150674, Abcam). All slides were immersed in a mixture of 1% potassium ferrohydride-hydrochloric acid for 30 min. Following this step, the slides underwent incubation with 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB)-substrate (Beyotime, China) and counterstained with hematoxylin to detect the HRP activity. To observe the liver specimens, the neutral resin was used to slice them before being examined them under an optical microscope.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

The liver tissue samples and Huh7 cells were extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) to isolate total RNA. The concentration of the extracted RNA was determined using a NanoPhotometer (Implen, United States). Subsequently, cDNA synthesis was performed using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit (Takara, Dalian, China), followed by qRT-PCR analysis utilizing the 2×SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Takara). The mRNA levels of the target genes were calculated relative to GAPDH using the 2−ΔΔCT method. The primer sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Western blotting

The RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime) containing 1% PMSF (Beyotime) was employed to extract total protein from liver tissue samples and Huh7 cells. The protein concentration was monitored using the BCA kit (Beyotime). Subsequently, 40 μg of protein samples were then subjected to SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. After blocking with 5% non-fat milk, the membrane was incubated overnight at 4 °C with antibodies against GAPDH (80570-1-RR, Proteintech), ZHX2 (ab205532, Abcam), YTHDF2 (ab220163, Abcam), GPX4 (ab125066, Abcam), SLC7A11 (ab307601, Abcam), and TFR-1 (ab214039, Abcam). Secondary antibodies were then applied for one hour. The protein signals were visualized using the ECL reagent (Beyotime) and analyzed for gray value using Image J software.

Cell culture and treatment

The Huh7 cells were obtained from Pricella (Wuhan, China) and underwent mycoplasma detection and STR authentication. They were then cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Solarbio, Beijing, China). To establish a cellular model of DM, the Huh7 cells were exposed to high glucose conditions (HG; 30 mM D-glucose), while normal glucose conditions (NG; 5.6 mM D-glucose and 24.4 mM mannitol) served as the control group. Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was utilized for transfection experiments to introduce overexpression vectors, and shRNA vectors, along with their respective controls, into the Huh7 cells.

Biochemical analysis

Liver samples were taken out from the −80 °C storage and diced, followed by homogenization. Subsequently, after centrifugation, the supernatant was isolated and preserved at −20 °C for future utilization. The levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), glutathione (GSH), malondialdehyde (MDA), and iron content in liver tissue, as well as Huh7 cells, were assessed using commercially available assay kits provided by Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute located in Nanjing, China.

MTT detection

The MTT assay was employed to assess the viability of Huh7 cells. A total of 5 × 103 cells were seeded in each well of a 96-well plate and incubated for 12 h. After transfection, the cells were further incubated for an additional 72 h. Following this, a solution containing 20 μL of MTT (5 mg/mL) was added to each well and incubated for 4 h. The supernatant was then removed and the formazan crystals were dissolved using dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Absorbance measurements were obtained using an automated microplate reader (BioTek SynergyH1, Winooski, USA).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

The ChIP assay was performed using the Simple ChIP kit (Cell Signaling Technology). Briefly, Huh7 cells were collected and cross-linked with formaldehyde. Subsequently, chromatin was fragmented by sonication to generate chromatin fragments typically ranging from 200 to 500 base pairs. Following an overnight incubation of the chromatin fragments with antibodies against ZHX2 (ab205532, Abcam) or normal rabbit IgG (negative control; Cell Signaling Technology), the immune complexes were captured using ChIP-grade protein G magnetic beads. After elution from the magnetic beads, DNA was purified and subjected to real-time PCR analysis utilizing specific primers designed for ZHX2 promoter regions. Primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)

All the specific procedures were conducted according to the protocol of the EZ-Magna RIP™ RNA-Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation Kit (Cat. # 17–701, Merck Millipore). In brief, cells were lysed using RIP lysis buffer and prepared through freeze-thaw cycles. After centrifugation, the supernatant was incubated with protein A/G magnetic beads conjugated with anti-YTHDF2 (ab220163, Abcam) or anti-m6A (ab195352, Abcam) antibody for 4–6 h. The immunoprecipitates were then eluted and treated with proteinase K before RNA extraction utilizing TRIzol. The relative interaction between YTHDF2 and target RNA was assessed by RT-qPCR and normalized against input. The primer sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

YTHDF2 transcriptional activity assay

The promoter regions of the human YTHDF2 gene were cloned into a pGL3‐basic luciferase reporter vector. To assess the activity of the YTHDF2 promoter, Huh7 cells were transfected with pGL3‐YTHDF2 and a Renilla luciferase plasmid for 24 h. The Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (Promega, E1910) was employed to measure the promoter activity, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The activity of the luciferase was normalized using a plasmid expressing Renilla luciferase.

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0, and the results were presented as means ± SD. Unpaired Student’s t-tests were employed to compare two groups, while one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was used to identify any statistical differences among multiple groups. A significance level of P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

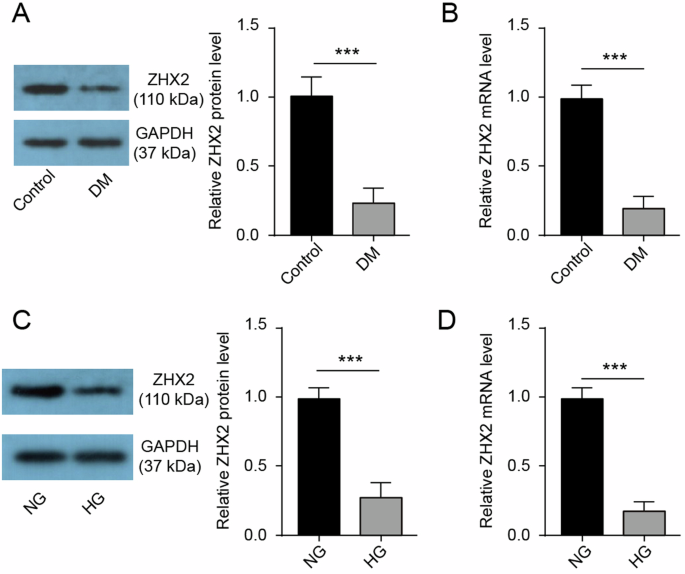

ZHX2 is decreased in the liver of DM mice and HG-induced Huh7 cells

We initially identified the presence of ZHX2 expression in the liver of diabetic mice through western blotting and qRT-PCR analysis. A noticeable decrease in both ZHX2 mRNA and protein levels was observed in the livers of diabetic mice compared to control mice (Fig. 1A, B). To simulate diabetes-induced liver injury in vitro, we exposed Huh7 cells to a high glucose (HG) environment for 72 h. Our findings revealed that the elevated glucose significantly suppressed the expression of ZHX2 at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 1C, D). In conclusion, our findings confirm that there is a reduction in ZHX2 levels within the liver tissue of diabetic mice.

A The western blotting technique was used to evaluate the protein expression of ZHX2 in the liver (n = 3). B The qRT-PCR method was employed to assess the mRNA expression of ZHX2 in the liver (n = 3). C, D Both western blotting and qRT-PCR were utilized to examine the expression of ZHX2 in Huh7 cells (n = 3).

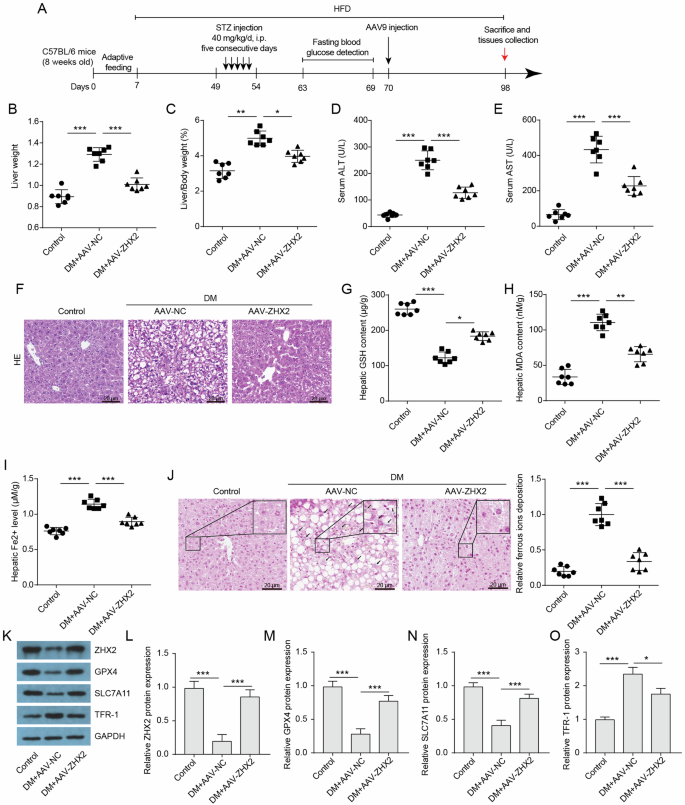

ZHX2 overexpression improves liver injury and ferroptosis in DM mice

We conducted further investigations into the impact of ZHX2 on liver injury in vivo. In order to establish a DM mouse model, we induced DM in mice through a high-fat diet and streptozotocin. Once the DM mouse model was established, we infected the mice with AAV-ZHX2 or AAV-NC via tail vein injection, followed by another 4 weeks of high-fat diet feeding (Fig. 2A). We observed an increase in liver weight and liver/body weight ratio in DM mice (Fig. 2B, C). However, when compared to the AAV-NC group, overexpression of ZHX2 significantly reduced liver weight and liver/body weight ratio in DM mice. ALT and AST are commonly used biomarkers for assessing hepatic damage, and our results confirmed that levels of ALT and AST were significantly elevated in DM groups compared to the control group, suggesting liver tissue lesions (Fig. 2D, E). Nevertheless, overexpression of ZHX2 was able to reverse these changes. Additionally, histological examination using HE staining revealed no significant pathological alterations in the control group; however, severe balloon degeneration, destruction of the hepatic sinusoidal structure, and accumulation of numerous fat vacuoles within normal cytoplasm were observed in the DM group (Fig. 2F). Therefore, our findings indicate that overexpressing ZHX2 can improve liver injury induced by DM.

A Schematic diagram of animal experiments. B Liver weight (n = 7). C liver-to-body weight ratio (n = 7). D, E Serum ALT and AST (n = 7). F Histological staining of H&E. Scale bar = 20 μm. G–I Hepatic GSH content, hepatic MDA content, and hepatic ferrous ions levels in the indicated groups (n = 7). J DAB-Prussian blue staining of ferrous ions in liver sections and quantitative analysis of ferrous ion expression (n = 7). Scale bar = 20 μm. K–O Protein expressions of ZHX2 and ferroptosis indicators, including GPX4, SLC7A11, and TFR-1, in the livers were assessed by western blotting (n = 3).

Ferroptosis, a form of programmed cell death that involves the iron-dependent peroxidation of phospholipids, plays a crucial role in liver damage caused by hyperglycemia [19, 26]. Our study observed significantly decreased levels of the antioxidant enzyme glutathione (GSH) in diabetic mice compared to control groups. This suggests an impaired antioxidant system in diabetic mice (Fig. 2G). Additionally, analysis of malondialdehyde (MDA), a marker for lipid peroxidation, revealed significantly elevated levels in the diabetic group (Fig. 2H). Furthermore, we found increased iron content in the livers of diabetic mice, indicating iron overload within liver tissues (Fig. 2I). The staining of ferrous ions using DAB-Prussian blue also demonstrated higher expression of ferrous ions in the livers of diabetic mice (Fig. 2J). These findings indicate that liver tissues from the diabetic group have a lower antioxidant capacity, higher levels of lipid peroxidation, and an excess of iron overload, all of which are hallmarks of ferroptosis. We also assessed the expression levels of key regulators involved in ferroptosis pathway including glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11), and transferrin receptor 1 (TFR-1), which is responsible for iron uptake. Notably, the protein levels of GPX4 and SLC7A11 were significantly reduced, while TFR-1 expression was upregulated in the livers of the diabetic group (Fig. 2K–O). Moreover, overexpression of ZHX2 successfully reversed ferroptosis-related changes and decreased ZHX2 expression observed within liver tissue samples from diabetic mice. Overall, our data indicate that ZHX2 inhibits ferroptosis in the livers of diabetic mice.

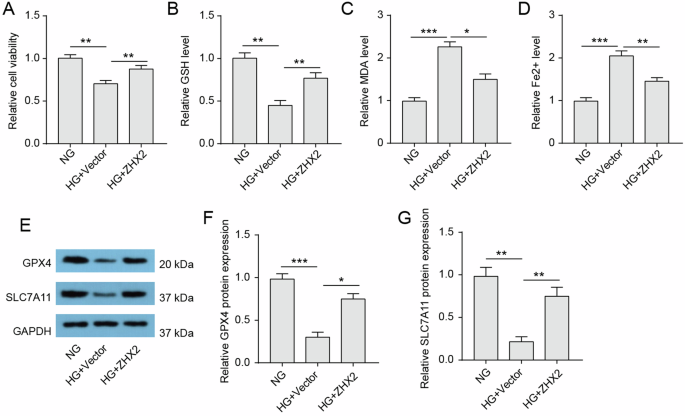

ZHX2 overexpression rescues HG-induced ferroptosis in Huh7 cells

The in vitro experiments have confirmed the role of ZHX2 in ferroptosis. Treatment with HG resulted in a decrease in cell viability of Huh7 cells, indicating that HG led to cell death in Huh7 cells (Fig. 3A). Additionally, HG-treated cells exhibited a significant reduction in GSH levels, an increase in MDA levels, and elevated ferrous ions content, suggesting the induction of ferroptosis by HG treatment in Huh7 cells (Fig. 3B–D). Moreover, western blotting analysis also revealed decreased protein expression levels of GPX4 and SLC7A11 in HG-treated cells, indicating impaired antioxidant capacity due to HG culture conditions for Huh7 cells (Fig. 3E–G). Importantly, overexpression of ZHX2 effectively reversed the observed changes associated with HG-induced ferroptosis. Taken together, these results demonstrate that upregulation of ZHX2 can restore HG-induced ferroptosis.

A Cell viability of Huh7 cells was assessed by MTT assay (n = 3). B–D Intracellular GSH, MDA, and Fe2+ levels in the indicated groups (n = 3). E–G Protein expressions of GPX4 and SLC7A11 in Huh7 cells were assessed by western blotting (n = 3).

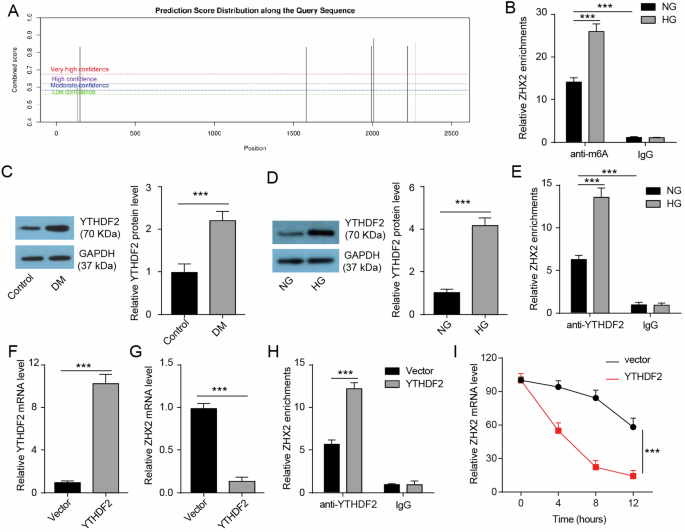

YTHDF2 promotes the degradation of ZHX2 mRNA

To investigate the underlying mechanism behind the decrease in hepatic ZHX2 expression in diabetic mice, we utilized SRAMP (sequence-based RNA adenosine methylation site predictor) to analyze the sequence of ZHX2 mRNA. Our analysis revealed multiple sites predicted to undergo m6A modification (Fig. 4A). Subsequently, an anti-m6A-RIP assay confirmed the presence of m6A modification on ZHX2 mRNA in Huh7 cells (Fig. 4B). We observed an elevated level of m6A-modified ZHX2 mRNA in HG-Huh7 cells compared to NG-Huh7 cells. Furthermore, we found that YTHDF2, a known RNA-binding protein capable of recognizing m6A-modified RNAs and promoting their degradation [27], was found to be upregulated in both liver tissue from diabetic mice and HG-induced Huh7 cells (Fig. 4C, D). Our RIP assay results further demonstrated the binding between YTHDF2 protein and ZHX2 mRNA (Fig. 4E), with this interaction being strengthened following HG induction. Overexpression of YTHDF2 significantly increased YTHDF2 mRNA levels while decreasing ZHX2 mRNA expression in Huh7 cells (Fig. 4F, G). Additionally, immunoprecipitation experiments showed a greater amount of ZHX2 mRNA being pulled down in YTHDF-overexpressing Huh7 cells (Fig. 4H). Furthermore, we performed mRNA stability profiling using actinomycin D-treated Huh7 cells to investigate whether YTHDF2 regulates the stability of ZHX2 mRNA. The results indicated that overexpression of YTHDF2 shortened the half-lives of ZHX2 mRNA significantly (Fig. 4I), suggesting that it inhibits its stability. Collectively, these findings suggest that YTHDF2 is implicated in the dysregulation of ZHX2 in DM-induced liver injury.

A SRAMP was used to analyze potential sites of m6A modification on ZHX2 mRNA. B RIP assay was performed to evaluate the level of m6A-modified ZHX2 mRNA (n = 3). C, D Western blotting was conducted to assess the protein expression of YTHDF2 in the liver and Huh7 cells (n = 3). E RIP assay in Huh7 cells was employed to examine the binding between YTHDF2 protein and ZHX2 mRNA (n = 3). F, G qRT-PCR was utilized to determine the mRNA expression of YTHDF2 and ZHX2 in Huh7 cells with or without YTHDF2 overexpression (n = 3). H RIP assay was carried out to investigate the binding between YTHDF2 protein and ZHX2 mRNA in Huh7 cells with or without YTHDF2 overexpression (n = 3). I qRT-PCR analysis was performed to assess the lifetime of ZHX2 ̧mRNA in Huh7 cells with or without YTHDF2 ̧overexpression (n = 3).

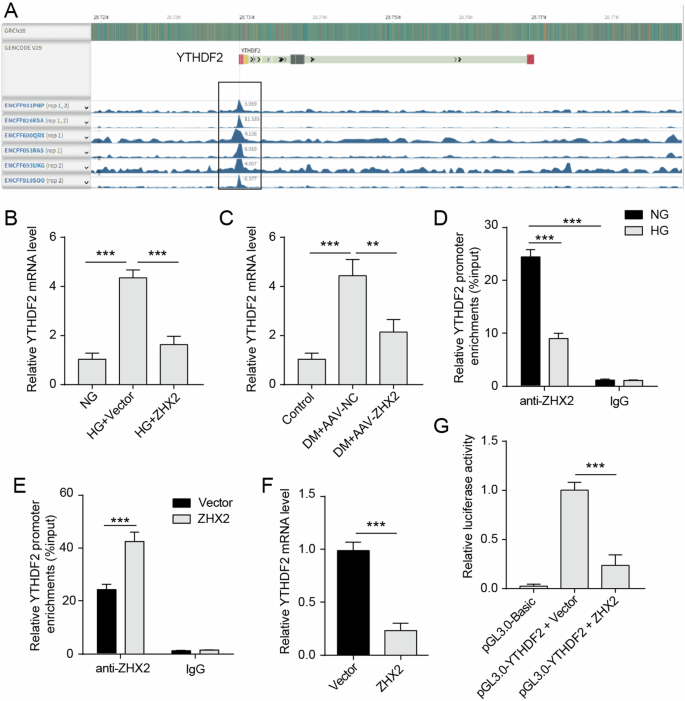

ZHX2 inhibits YTHDF2 transactivation

Based on ChIP-seq data obtained from ENCODE, we observed an enrichment of the transcription factor ZHX2 in the promoter region of the YTHDF2 gene in HepG2 cells (Fig. 5A). Overexpression of ZHX2 reversed the upregulation of YTHDF2 induced by HG (Fig. 5B). In DM mice, overexpression of ZHX2 led to a reduction in hepatic YTHDF2 mRNA levels (Fig. 5C), suggesting that ZHX2 may inhibit YTHDF2 expression by suppressing its transcription. To confirm this, we performed a ChIP assay and found that ZHX2 protein was enriched at the promoter region of the YTHDF2 gene in Huh7 cells (Fig. 5D). This enrichment of ZHX2 was further reduced under HG-induced conditions. Furthermore, overexpression of ZHX2 increased its enrichment at the promoter region of the YTHDF2 gene (Fig. 5E) and decreased YTHDF2 mRNA expression in Huh7 cells (Fig. 5F). Importantly, luciferase reporter gene assays revealed a significant decrease in activity for the YTHDF2 promoter reporter when ZHX2 was overexpressed in Huh7 cells (Fig. 5G). Based on these findings, it can be concluded that ZHX2 suppresses transcription and expression of YTHDF2.

A ENCODE was used to visualize the enrichment of ZHX2 in the YTHDF2 gene in HepG2 cells. B, C The mRNA expression levels of YTHDF2 were examined in liver and Huh7 cells (n = 3). D ChIP assay was used to detect the enrichment of ZHX2 at the promoter region of the YTHDF2 gene in Huh7 cells treated with NG or HG (n = 3). E ChIP assay was used to detect the enrichment of ZHX2 at the promoter region of the YTHDF2 gene in Huh7 cells with or without ZHX2 overexpression (n = 3). F The mRNA expression of YTHDF2 in Huh7 cells with or without ZHX2 overexpression (n = 3). G The YTHDF2 promoter reporter luciferase activity in Huh7 cells with or without ZHX2 overexpression (n = 3).

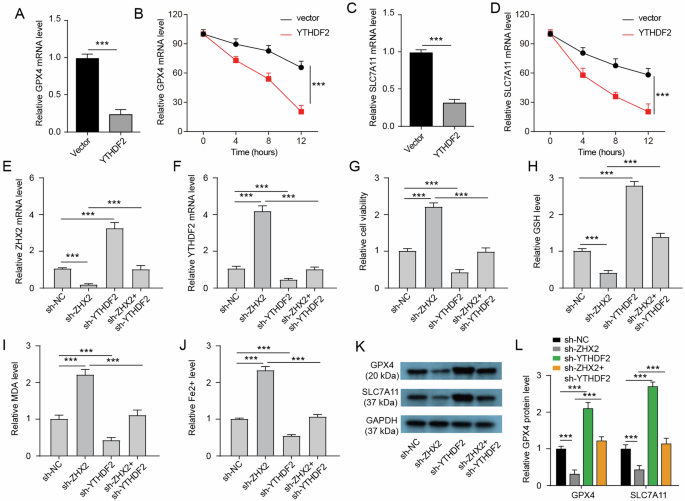

ZHX2 regulates ferroptosis by inactivating YTHDF2-induced GPX4 and SLC7A11 degradation

YTHDF2 has been reported to be involved in the regulation of ferroptosis by facilitating the degradation of GPX4 and SLC7A11 mRNA [28]. Here, we confirmed that overexpression of YTHDF2 could downregulate GPX4 mRNA expression and impede its stability in Huh7 cells (Fig. 6A, B). Similarly, YTHDF2 overexpression also suppressed the level and stability of SLC7A11 mRNA in Huh7 cells (Fig. 6C, D). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that ZHX2 may inhibit ferroptosis through deactivating YTHDF2. To test this hypothesis, we used specific shRNA to knock down ZHX2 or YTHDF2 in HG-induced Huh7 cells (Fig. S1A, B). ZHX2 knockdown significantly decreased ZHX2 mRNA levels while increasing YTHDF2 mRNA levels (Fig. 6E, F). Conversely, YTHDF2 knockdown led to a reduction in its mRNA levels but an increase in ZHX2 mRNA levels. The upregulation of YTHDF2 induced by ZHX2 knockdown was reversed upon subsequent knockdown of YTHDF2 itself. We observed enhanced cell viability, reduced GSH levels, elevated MDA levels, and increased Fe2+ content in ZHX2-depleted Huh7 cells compared to the sh-NC group (Fig. 6G–J). Furthermore, the depletion of ZHX2 resulted in reduced protein expression of GPX4 and SLC7A11 in HG-induced Huh7 cells (Fig. 6K, L). The knockdown of YTHDF2 rescued these changes induced by the inhibition of ZHX2. Besides, ZHX2 overexpression inhibited ferroptosis, which was reversed by YTHDF2 overexpression (Fig. S2A–L). Collectively, these results indicate that inhibition of ZHX2 promotes ferroptosis by activating YTHFD2-mediated degradation for GPX4 and SLC7A11.

A The mRNA level of GPX4 in Huh7 cells with or without YTHDF2 overexpression (n = 3). B The stability of GPX4 mRNA in Huh7 cells with or without YTHDF2 overexpression (n = 3). C The mRNA level of SLC7A11 in Huh7 cells with or without YTHDF2 overexpression (n = 3). D The stability of SLC7A11 mRNA in Huh7 cells with or without YTHDF2 overexpression (n = 3). E, F The mRNA level of ZHX2 and YTHDF2 in Huh7 cells with indicated transfection and HG induction (n = 3). G The cell viability of Huh7 cells with indicated transfection and HG induction. H–J Intracellular GSH, MDA, and Fe2+ levels in Huh7 cells with indicated transfection and HG induction (n = 3). K, L Protein expressions of GPX4 and SLC7A11 in Huh7 cells with indicated transfection and HG induction (n = 3).

Discussion

In this study, we have observed that ZHX2 exhibits a notable capacity to counteract ferroptosis in the livers of mice with diabetes. The advantageous impact of ZHX2 is achieved by deactivating YTHDF2 and its downstream targets GPX4 and SLC7A11 in both in vivo and in vitro models of diabetes. Additionally, YTHDF2 suppresses the expression of ZHX2 by reducing the stability of m6A-modified ZHX2 mRNA. Notably, there is a feedback loop between ZHX2 and YTHDF2 within the livers of diabetic mice. These findings collectively suggest that targeting the ZHX2-YTHDF2 loop may be a promising therapeutic approach for managing MASLD in patients with diabetes.

Diabetes is a complex metabolic disorder that affects multiple physiological systems and manifests as elevated blood glucose levels. This condition gives rise to complications that significantly impact quality of life and increase mortality rates. There are two primary classifications of diabetes: type 1 (T1D) and type 2 (T2D). T1D results from an autoimmune attack on the beta cells of the pancreas, which are responsible for insulin production and regulation of blood sugar levels. Consequently, this leads to inadequate insulin production, causing hyperglycemia and impaired cellular uptake of glucose. As a result, individuals with T1D require lifelong administration of insulin for effective management of their blood sugar levels. In contrast, T2D is characterized by insulin resistance along with relative insufficiency in its secretion due to factors such as obesity, sedentary lifestyle, or genetic predisposition [29]. Lifestyle modifications and oral medications can be employed to manage this form of diabetes. The majority of diabetes cases are classified as T2D, accounting for over 90% of all instances. In contrast, T1D is a much rarer form of the disease and only affects less than 5-10% of individuals [30]. While it was believed that T1D primarily affected children, adolescents, and adults [31, 32], it is now known that T2D commonly occurs among elderly individuals, and more than half of all cases can be attributed to obesity.

Short-term diabetes typically denotes the acute exacerbation of the condition, which may be triggered by stressors, dietary influences, inadequate treatment, and specific forms of diabetes [33]. Nevertheless, the etiology of chronic diabetes is predominantly associated with genetic predispositions, environmental determinants, and immune system factors [34, 35]. Short-term diabetes manifests more abruptly, whereas diabetes generally progresses more insidiously and may present with minimal symptoms in its initial stages. Some patients might remain unaware of their condition until they exhibit signs of chronic complications. Symptoms commonly associated with short-term diabetes can often lead to elevated blood glucose levels and denote the acute complications associated with diabetes, including diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state, which arise from a rapid elevation in blood glucose levels [36,37,38,39]. In contrast, chronic diabetes pertains to the long-term complications of the disease [40,41,42], such as cardiovascular disorders, diabetic nephropathy, and diabetic retinopathy; these conditions primarily result from sustained damage to various organs due to prolonged hyperglycemia. Immediate medical intervention is essential for acute diabetes management, necessitating treatment strategies such as intravenous insulin administration and fluid resuscitation to swiftly reduce blood glucose levels and rectify metabolic derangements [43]. Conversely, chronic diabetes management requires ongoing regulation of glycemic control alongside monitoring of blood pressure and lipid profiles to mitigate the onset and progression of complications [44]. Effectively managing chronic diabetes can be challenging and frequently involves ongoing treatment interventions such as dietary modifications, physical activity interventions, or pharmacological treatments [45, 46].

Initially recognized as a widely distributed transcription factor, ZHX2 has been found to play significant roles in various biological processes such as development, metabolism, and cancer. Interestingly, ZHX2 has been found to exhibit tumor suppressor activity in liver cancer [47], thyroid cancer [48], and multiple myeloma [49]. However, it appears to play a role in promoting the development of clear cell renal cell carcinoma [50] and triple-negative breast cancer [51]. These findings strongly suggest that the effects of ZHX2 are dependent on the specific context. Moreover, recent findings by Zhao et al suggest a decrease in ZHX2 levels during MASH development, where it plays a role in alleviating MASH through activating PTEN transcription [25]. According to Wu et al, the expression of ZHX2 was found to be notably reduced in fatty liver tissues, particularly in livers affected by MASLD-HCC. Their findings suggest that the depletion of ZHX2 contributes to increased lipid accumulation and facilitates the progression of MASLD [24]. In line with these findings, our current study demonstrates the downregulation of ZHX2 specifically within the livers of DM mice. Notably, we observe significant recovery from DM-induced liver injury upon overexpression of ZHX2. These findings enhance our comprehension of the biological roles of ZHX2 in liver pathophysiology and suggest that ZHX2 plays a crucial role in the development of MASLD.

Initially known for its role in suppressing gene promoters associated with hepatocellular carcinoma, ZHX2 has also been found to inhibit the activity of various genes like alpha-fetoprotein, H19, glypican-3, Cyclin A, and Cyclin E [21, 23, 52, 53]. Recent studies have revealed additional biological functions of ZHX2 where it acts as a significant transcriptional activator by promoting the expression of genes such as fructose-2,6-biphosphatase/6-phosphofructo-2-kinase 3 involved in glycolysis [54]. Moreover, ZHX2 has been found to bind to the promoter region and activates the PTEN gene [25]. In the present study, we have identified YTHDF2 as a target gene of ZHX2. Through direct binding to its promoter region, ZHX2 exerts inhibitory effects on the transcriptional activity of YTHDF2. Acting as an m6A reader, YTHDF2 plays a crucial role in regulating ferroptosis. In cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury, YTHDF2 facilitates cardiac ferroptosis by breaking down SLC7A11 [55]. Similarly, it contributes to the degradation of SLC7A11 mRNA in hepatocellular carcinoma [56]. Moreover, through recognition and degradation of m6A methylation modification sites on GPX4 mRNA, YTHDF2 is implicated in AKT inhibition-induced ferroptosis [57]. Additionally, Qiao et al have confirmed that both SLC7A11 and GPX4 serve as targets for YTHDF2 in colorectal cancer [28]. In this study, we further validate that YTHDF2 reduces the stability of SLC7A11 and GPX4 expression in Huh7 cells, thereby promoting ferroptosis. Additionally, inhibition of ZHX2 promotes ferroptosis by activating the transcription of YTHDF2. Our study establishes a novel association between ZHX2 and ferroptosis, wherein ZHX2 inhibits DM-induced liver ferroptosis by deactivating YTHDF2-mediated degradation of GPX4 and SLC7A11. Collectively, our findings highlight the crucial involvement of the ZHX2–YTHDF2-ferroptosis signaling pathway in DM-induced liver injury.

In summary, our research provides valuable insights into the molecular mechanism responsible for liver damage caused by DM and highlights the protective role of ZHX2 in mitigating DM-induced liver injury through its interaction with the promoter region of YTHDF2, resulting in the suppression of YTHDF2 expression. These findings offer promising prospects for therapeutic interventions targeting the ZHX2-YTHDF2-ferroptosis signaling pathway as a potential treatment strategy for DM-related liver injury.

Responses